When I asked my co-worker what he was doing over the weekend, he said “nothing.”

After a brief pause, he said he was taking the hinges off the doors in his house and soaking them in Coca-Cola to remove the tarnish. He removes them, cleans and replaces them one by one so as not to mix them up.

I, too, would have said my weekend would consist of nothing, but a different “nothing” from my co-worker’s. “Nothing” often means house projects, and house projects are a definite marker of adulthood. I rent; I have yet to cross the homeowner threshold. However, I do claim adulthood by the degree to which I have graduated to doing nothing on weekends — and finding it enjoyable.

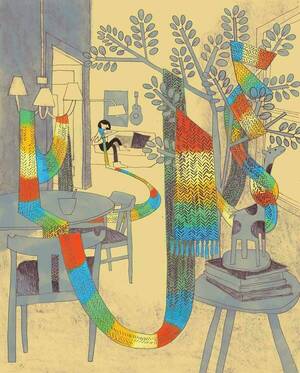

The “nothing” adults enjoy is not that of a sullen teenager who would like to keep aspects of her life private from her parents. It is more like the process of gathering up the loose ends of the week. If our week is a scarf that unravels its threads, the weekends are a time to sit still and draw those various threads back to our center.

Recently I spoke to someone who was planning to finish several work projects within the coming week. She anticipated taking her use-or-lose leave before the end of the year. “What will you do?” I asked. “Will you go anywhere?” No, she replied. She was looking forward to relaxing at home.

What she was really looking forward to was cleaning her baseboards.

An aside, in the spirit of “nothing”: What is a baseboard? Does the wall-to-floor connection need to be hidden? I can’t see what purpose baseboards serve except as toddler-accessible ledges that collect dust. Growing up, I was sometimes tasked with vacuuming baseboards. Perhaps parents once needed a way to initiate children’s performance of chores. Let Mom and Dad handle the lamps; here, scoot the rag along this shoe-height ledge. Examining the periphery of my bedroom, I observe that at the bottom of the baseboard is another dust-collecting ledge. I contemplate a series of infinitely regressing chores.

Chores have that winding way of inviting themselves into smaller and smaller chambers. We start with clear intentions — emptying a bathroom drawer, wiping down the fridge, sorting a financial file — but soon arrive at something unexpected. Like a city walking tour that starts smartly on a main street but somehow ambles down a side alley, we are led down paths we would not have predicted at the outset. We are left somewhere quiet, lifting questionable souvenirs into the light — a crusty perfume bottle, an expired jar of olives, a thank-you card from a former co-worker — miles away from the main thoroughfare.

When I finish cleaning my closet, I unfold from a stooped position like a creature emerging from another universe. I am stiff-legged, lightheaded, and my eyes adjust to daylight and distance vision as if to a different atmospheric pressure. My constellation of symptoms mirrors my emotional limbo state. I am unsure if I feel lighter for having cleaned out one 10-by-6-inch compartment, or heavier for knowing just how many such compartments my life contains.

Nothing: This weekend, I wiped my glasses with a lens cloth. Over the past few weeks, I began to notice how the nose pads were collecting black and green gunk. I threaded a lens wipe through the gap between the pads and the frame. Shimmying it back and forth, the white cloth showed streaks of color. Encouraged, I wondered whether some finer tool might perfect the job. I found a toothpick, but even as I set to work, I thought, What if this doesn’t cut it? Would another tool work better? This is the type of epiphanic quest I hope for on a weekend.

When a co-worker asks about my weekend, and I have an event planned, I reference it in offering. “I’m celebrating a friend’s birthday,” I say. “Nice,” they nod. I’ve accounted for only 5 percent of my weekend time, yet my answer suffices. If my supervisor asked me to account for my time, maybe I’d itemize my activities, but with a co-worker I go for the standard deduction.

Otherwise, I’m being truthful, albeit abstract. “Nothing” means something I don’t want to name. If I named it, I would be committing to it, which is precisely what I don’t want to do. It’s not nothing, per se, but it’s mine, and it’s mine to the degree to which I cannot explain it to you.

Erin Buckley lives in Richmond, Virginia, where she works as an occupational therapist.