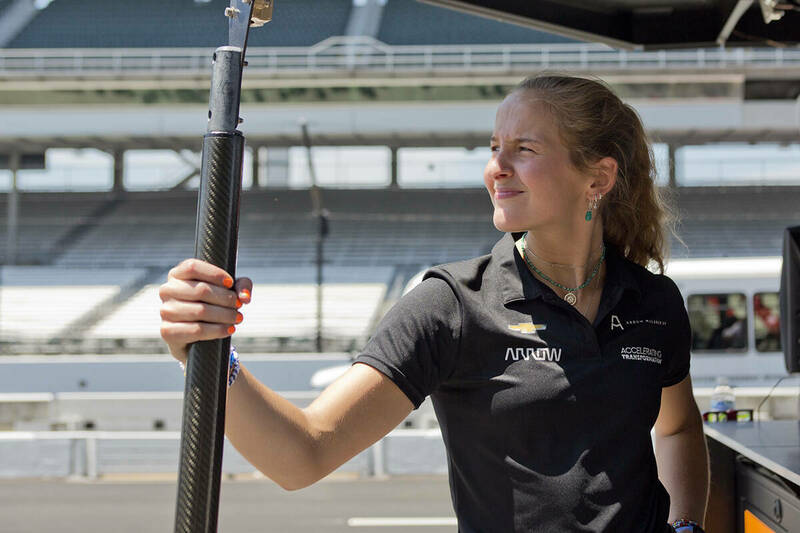

Lindsay Falk at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Photos provided

Lindsay Falk at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Photos provided

It became a family event in the Falk household. It was the weekend, but alarms would often go off around 6 a.m. Lindsay, who was finishing up high school, would go downstairs and start some coffee. Ryan, three years younger, would be changing into his race-day outfit to watch that Saturday’s Formula One qualifying or the Sunday race.

Ryan, who grew up loving cars, was the family’s first motor sport aficionado. His mom, Julie, started watching races with him. Eventually, his father, Erik, and Lindsay joined in, especially as the family became fans of Drive to Survive, the Netflix documentary series that has drastically increased the sport’s popularity in the U.S.

Soon, Lindsay and Ryan were not just watching the races on TV. Armed with a premium F1 online subscription, they pored over live data, followed the onboard cameras and discussed potential strategies for every car.

By last summer, Lindsay and Ryan had taken over Erik’s home office. The obsession over race data, however, was no longer leisure. Then a rising junior electrical engineering student, Lindsay was an intern with IndyCar team Arrow McLaren SP. She helped the team’s race engineers manage their cars’ fuel levels on-site at races, from the team’s headquarters in Indianapolis or the “war room” she created in her father’s office. From home, Lindsay could communicate with the team’s pit crew remotely. Ryan recalls being “the spy,” listening to other team’s radios (which, he notes, are publicly available).

“It sounded like we were in a racetrack in our own house,” Julie remembers.

As Erik and Julie watched the race on the living room TV, they received updates from Lindsay about what was about to unfold. Her inside information repeatedly proved correct.

“We were laughing,” Julie says, “because we thought, ‘Wow, she really knows what she’s talking about.’”

Leaving enough in the tank

After contracting COVID in 2021, Lindsay quarantined at home outside Chicago. Normally, she busies herself with frenetic action: doing homework while on a stationary bike, and spending time not spent at rowing practice with student engineering groups.

Bored in quarantine without those activities, Lindsay started firing off emails to IndyCar teams inquiring about potential opportunities. (She knew obtaining a permit to work short-term for an F1 team in Europe wasn’t realistic.)

Two weeks later, Lindsay was zoned out in math class when a text popped up on her iPad: “Hi Lindsay, this is Craig Hampson from McLaren racing.”

Lindsay immediately recognized the name of one of McLaren’s most established race engineers. That afternoon, she talked with Hampson about Notre Dame football (his wife, Helen, is a ’94 grad) and how the racing team hoped to establish a program for acquiring young talent.

Other teams replied to Lindsay, but none could match the prestige of McLaren, the only team to win motorsport’s “Triple Crown”: F1’s Monaco Grand Prix, IndyCar’s Indianapolis 500 and the 24 Hours of Le Mans (the world’s oldest active endurance race). When she first started watching F1, Lindsay became a McLaren fan thanks to her brother’s fandom for rising star Lando Norris.

When she arrived in Indianapolis for her summer internship, Lindsay thought she would be given busy work and spend most of her time watching from the sidelines.

“But on the first day (the interns) walked into the shop, we were literally allowed to touch the car,” Lindsay says. “I was allowed to put the steering wheel in and sit in the car and help with the clutch calibrations starting on day one.”

When the interns were given side projects, Lindsay’s job was to use a coding system to clip live video from the car at specific points on the track. When the drivers come in for a pit stop or rest between practice or qualifying sessions, they now can review a mistake or determine the ideal racing line at that part of the track. The first race after Lindsay had finished the project, her work was already being used in the engineering truck.

“I thought that was really cool,” she says.

Lindsay also helped the engineers handle the dilemmas of fuel management. To run as fast as possible, teams aim to use the minimum amount of fuel needed to finish. In IndyCar, each car gets one sensor that informs the driver and team when there is one gallon left in the tank.

Unlike F1, refueling during pitstops is permitted in IndyCar. The catch, Lindsay explains, is that more than one gallon is needed to complete a single lap on most tracks. Before the sensor is triggered, it’s up to teams to estimate how much gas is left.

Lindsay would monitor how hard the car was being pushed and whether the current fuel mixture was rich — which increases the maximum power of the engine but is less efficient — or lean, for which the opposite is true. Using that data, Lindsay would help the team strategize when to make pit stops and secure the best finish possible without running out of fuel.

Often, race engineers set bold strategies that leave little room for error. Drivers don’t like hearing they need to coast more into corners. As a fellow racer, Lindsay can sympathize.

In both auto racing and rowing, tenths, even hundredths, of a second separate competitors.

“It’s a very similar mentality where every choice that you make matters,” she says. “In racing sports, you see the victories come and slip away as it’s unfolding. It’s kind of having to balance the calmness with that hot-headed desire to come out first, when you're literally watching someone pass you and not knowing if you can get (the place) back.”

“My life sport”

The Falk family moved from New York to Winnetka, Illinois, before Lindsay’s sophomore year of high school. Always a fierce competitor who had excelled in multiple sports and Model UN — “practically a bloodsport,” her mother, Julie, recalls — she didn’t make the volleyball team at Winnetka’s New Trier High School. Julie suggested she dust herself off and show up at rowing tryouts the following Monday morning at 9 a.m.

Around noon, Julie arrived to pick Lindsay up.

“Mom,” she remembers Lindsay saying as she hopped in the car, “I think I found my life sport.”

After winning a national championship with New Trier, Lindsay came to Notre Dame in 2020, when the Irish were still training in pods amid the pandemic. On the ergs, or indoor rowing machines, Lindsay believes she pulled the slowest times among all the freshmen.

But in her first season, she earned a spot in the second varsity eight, one of the three boats that earn points in NCAA competition. Last year, she moved up to the front of the boat and set the pace as the stroke, a role she also performed this year at times for the first varsity four.

“I think I had a lot more success right away than I expected,” Lindsay says, “and I think a lot of that is because of the way that I think about rowing and (the way) I think that my coaches think about rowing, which is kind of breaking it down into the physics and breaking down the numbers.”

Her head coach at Notre Dame, Martin Stone, shares Lindsay’s F1 fandom. Now, it’s a constant source of banter.

“Part of what’s made our relationship so good is that we have a separate interest or a separate space that we like to talk about outside of rowing,” Lindsay says. “And then we can kind of clash heads in rowing.”

Lindsay calls herself “very opinioned and a little bit headstrong.” Stone wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Lindsay wants to be a race engineer at an F1 team,” he says. “There’s going to be definite pushback, right?”

“You feel eyes on you”

Lindsay estimates there were eight or nine male faces for every woman in the engineering truck. “You feel eyes on you immediately walking through,” she says. “And part of that is pretty empowering, because the only reason people care to look is because they’re surprised.”

Nonetheless, Lindsay remembers being a bit reticent, afraid of asking questions while trying to prove she belonged. She found a mentor in performance engineer Kate Gundlach, who would talk honestly about working as a woman in a largely male-dominated space.

When she and Lindsay prepped together for a race in Nashville near the end of Lindsay’s internship, Gundlach offered a piece of encouragement and advice that stuck.

“I see that you’re really smart, and you know what you’re doing,” she told Lindsay. “But I also see that you’re holding back in asking (questions). . . . I think the biggest thing that held me back originally in my career was being afraid that people wouldn’t take me seriously.”

In her engineering courses, Lindsay is often the only or one of a few women. She felt a temptation to be reserved in the classroom, but that changed during her sophomore year.

“I decided, no, I want to wear my floral, floor-length dresses and do my makeup and have fun with that,” she says. “And be loud and ask questions and be funny, and not hold any of that back. I’d just rather be happier. And I’d rather be out there and have everybody know who I am.”

During the 2022 fall semester, Lindsay carved out time to continue helping Arrow McLaren, again creating a mini “war room,” this time with her laptop and iPad in Breen-Phillips Hall. After a hiatus during the rowing season, Lindsay is back to work in-person this summer.

Even when she’s busy competing herself, auto racing is never far from her mind. In late April, on the bus headed home from a rowing competition, she asked in the family group chat if anyone wanted to watch the replay of that morning’s qualifying session for the Azerbaijan Grand Prix.

Ryan started the video on a couch at home in Illinois, ready to swap data points.

Greg McKenna was the editor-in-chief of Scholastic this past year. He studied history, economics and journalism at Notre Dame. An incoming intern at The Boston Globe, he’s also worked for the Tampa Bay Times and South Bend Tribune.