Spring 1993. I survey our apartment, contemplating how I can possibly move all these books, papers and sentimental tchotchkes — to say nothing of our Brooklyn vocabulary — when Chris calls from South Bend. House hunting, he tells me he’s standing at an upstairs window in an old brick house, gazing down on a big group of black, white and brown kids shooting hoops next door. They’re making a ruckus, having a grand old time. “It looks like the P.S. 321 schoolyard. It feels like . . . Brooklyn.”

My husband sells me that South Bend house sight unseen. We’re dazzled by the very idea of a house — our 20 years of married life have been spent in apartments — and our requirements are simple: We want a city house. It will be hard enough to leave the greatest city on the planet and a neighborhood where we recognize every kid chalking up the sidewalk. If we’re moving to a new burg, however much smaller, we mean to make it ours. We want our two sons to play on blocks filled with children of every color and creed, to walk to the library downtown, to bike in parks and trails along the river. We want old houses with history and neighbors who hang out on summer nights. We want ruckus. I’ve had two quick visits to South Bend and found plenty of neighborhoods I could love, but now, from afar, I commit to Harter Heights.

All great cities are filled with distinctive neighborhoods, each with its own smells and rhythms and vibe. That August we roll into South Bend ready to embrace ours, a walk from the city center and Notre Dame. I have only the vaguest visual memory of Harter Heights, bordering the Notre Dame golf course, and my move-in sighting of stately colonials along Angela Boulevard surprises me. “We live in Beaver Cleaverville,” I say with a laugh, but our sons were born too late to know about Leave It to Beaver’s idealized, prosperous TV neighborhood. They’ve never read Booth Tarkington, either, so I dispense with the Penrod reference.

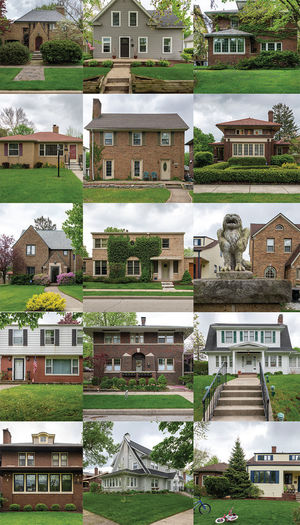

After we make a turn, I remember how varied the architecture is here, how 80-year old Tudors abut small, ’60s-style ranch houses. Modernist experiments in angularity sidle up to classical Italianate proportions. Trees — maple and black walnut and sweet gum — have risen with every decade of construction, and now they drape over sidewalks in lazy stretches. Our boys are quick to note the passing street signs, Pokagon and Peashway. Our own street’s named Napoleon, so we’ll have ongoing reminders that colonial powers once wrested this land from the Potawatomi.

Now we are the guilty conquerors of urban good fortune. Our boys have never before had their own bedrooms or yard or stalwart, red-brick house approximating a foursquare, minus the requisite full stretch of porch. Ours is a city house, all right — if we come out the side at the same time as our neighbors, the doors air-kiss. But what, where, are the smells and the rhythms of our new neighborhood? On our first afternoon, they’re elusive, too subtle for us to locate. No bodegas or sidewalk fruit carts here: These streets look almost suburban. Midwestern Nice.

The next morning, not one but two neighbors knock with offerings. We learn that the August smell of this neighborhood is farmers-market peach, baked into crumb cake and pie. The sound is the high pitch of kids squealing outside. We meet neighbors on both sides from New York, which is both reassuring and intimidating: How did conversation-happy New Yorkers learn to trim their lawns with this military precision? We’re surrounded by Notre Dame faculty and coaches and staff. “Ah, you landed in the bosses’ neighborhood,” a colleague says. His neighborhood is where the workers lived.

I protest that we chose these streets because they looked so diverse, but I already see how locals might connect this neighborhood to the manufacturing history of South Bend, to Studebaker and Singer sewing — and how they might put much of our neighborhood on the power side of the scale. At one end of Harter Heights, the houses are, for the most part, spacious, handsome, even grand. In the middle, an aging neighbor tells me how her father and brother went to the train station to pick up their Sears, Roebuck house kit. Despite its unassuming origins, that house, too, still looks imposing and gracious. We live at the very edge of the official boundary: Down Napoleon, houses gradually shrink till they become matchboxes built for returning World War II vets. On our walk downtown, lawns lose their air of uniform precision, tidy edges gone AWOL. “Be careful walking,” a neighbor warns. “We’re in the inner city.” After Brooklyn, we find this hilarious.

But we do want to see the inner life of South Bend; after all, it’s the daily observation of different lives that we crave. I’m pleased to learn that New Yorker Alfred Kazin, famed literary critic and author of A Walker in the City, was once in residence at Notre Dame. We’re now walkers in South Bend, and it’s on our hikes that we meet not just the neighbors but the adjacent neighborhoods. We tramp a dirt path by the St. Joseph River soon to become the East Bank Trail, where we encounter joggers with the latest techno-shoes and homeless men with torn sleeping bags. The excellent library downtown hosts all manner of people working to cheer our new city out of its Rust Belt woes. We check out the whiz of rush-hour traffic along Michigan Street, the city’s main artery, and consider the shift workers of South Bend.

But we’re also content to sit in the evenings on our porch, watching friends stroll by and inviting them in to porch-sit over a glass of wine. Our neighbor Rickey Bonds rolls his wheelchair out to the corner and draws the neighborhood into his orbit. He watches over the street, and the street comes to him, drawn by his warmth. In the winter snow we often waken to immaculate sidewalks: An anonymous neighbor-elf has cleared the entire square block before heading off to work.

We watch Harter Heights children grow up alongside ours; then, as our sons leave home, we watch a whole new army of children who look too young to walk, much less navigate, invade the sidewalks with skateboards, rollerblades, scooters. This neighborhood bursts with children who pet our dogs, rake our leaves, tell us amazing facts about bugs. Two houses down a large family plays together in their backyard: It tickles us to hear how patiently the older ones teach the young a new trick. One of the girls has a haunting voice, and when I hear her singing I always stop to listen. That girl, Kate Mullaney Shirley ’11, will be my honors-thesis student one day, and I’ll be in the audience for her triumphant senior recital. After her family moves, another delightful former student, Annie Walorski Morin ’05, ’07M.Ed., and her husband, Eric ’05, ’07M.Ed., ’15M.A., renovate the house, and soon enough we hear their children singing and teaching each other new tricks.

The first time we receive a flyer for an ice-cream social, we know we live in a Midwestern dreamscape. Harter Heights watches over its sidewalk urchins with barbecues and a longstanding, Wednesday-night, backyard Wiffle ball game organized by Julie and Joe Urbany, professor of marketing. We have no skin in the game but think up excuses to walk by and hear the joyful racket. Word goes out over the same group email that brings us news of runaway cats hiding in alleys, outgrown cribs and desks for the taking, petty crime. We’ve even come to know our local break-in artists, including a pair of roguish middle-aged twins who, neighborhood legend has it, provide each other handy alibis. Lately, the emails have carried news of a petition to install speed bumps and, like so many neighborhoods’ communiqués, offers to help anyone shut in because of COVID-19. Every now and again, someone mentions a family who’d like to move in, and that has me thinking.

A few houses have become football rentals occupied just a few weekends every year, only ghost-children singing in those empty yards. Over the years, we notice, too, that Harter Heights has the same problems as America: Rising housing costs and growing inequality have made our neighborhood less diverse. Ours may be an elusive vibe, and honestly, we’re nothing like Brooklyn — but we couldn’t be more welcoming. Sometimes it takes a neighborhood effort to draw folks of all colors and creeds, and maybe we need to get the word out. Wanted as neighbors: folks who like sidewalk action, walks downtown, Wiffle ball. Folks who want a scrappy, neighborly city.

Valerie Sayers is the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of English and author of six novels and a forthcoming collection of stories.