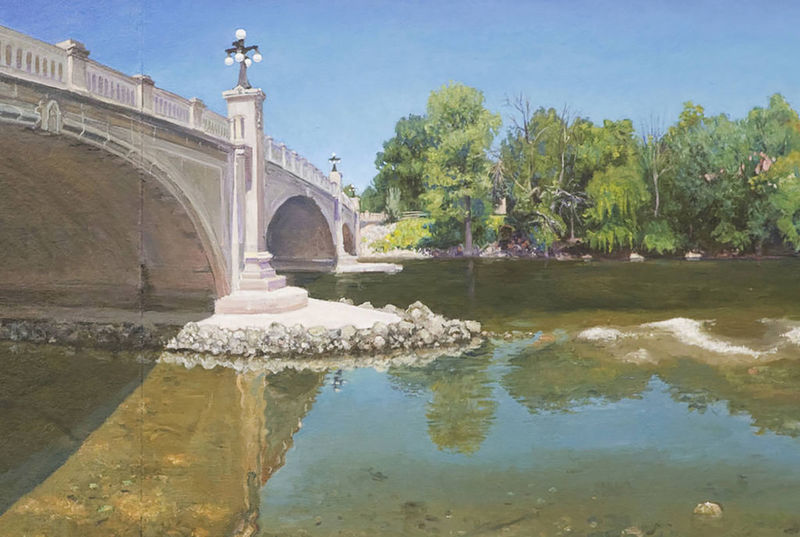

Painting by David Allen

Painting by David Allen

South Bend is a river town. The city’s very name derives from the wending ways of the St. Joseph River. People have long congregated along its waters, with native inhabitants fishing its depths, fur traders building cabins near its banks, and the city’s nascent industry being powered by the St. Joe’s flow.

Notre Dame’s lakes are famous. Saint Mary’s Lake and Saint Joseph’s Lake are built into the foundations of the University, their mud yielding the bricks that were shaped into some of campus’ most venerable structures. Students jog their shores. They paddle across in makeshift boats. And if they kneel in prayer at the Grotto, they will likely hear the honking of rowdy geese at the landing, but they won’t hear a trickle from the St. Joseph River.

Like town and campus for much of our history, the lakes and the river are linked but distinct. Indeed, the river can serve as a sort of border, carving out some distance between the University and the unruly city adjacent. Even as Notre Dame’s reach expands, growing into the shops and town houses of Eddy Street Commons or the wraparound porches and spacious lots of Notre Dame Avenue, the University hasn’t shown much appetite for crossing that natural boundary.

I spent much of my life on the Notre Dame side of the river. Just a few blocks from my childhood home it takes a sharp bend northward, leaving its westerly course beneath Michigan Street to turn up past Saint Mary’s College and across the state line into Michigan.

I crossed the river daily, walking to and from Madison elementary school. But I ventured closer, too, mucking along the shoreline to place my feet in the mud beneath the Michigan Street Bridge and wading out to the sandbar in summer to collect mysterious shells — long, black and flaking, like a span of steel exposed to caustic waters.

Once, on a dare, I crawled across an abandoned trestle bridge that spans the river just north of Angela Boulevard. I was too scared to walk upright. Years later, a boy fell from that same span and drowned. Thinking back on our separate paths, I can only conclude how fragile life is and how randomly we arrive at our different destinations.

I left my riverside home to make the short trip — not two miles — to Notre Dame in the late ’90s. The distinction between home and college was a soft one; I’d spent years around the quads, tailgating before football games, crashing student events at The Huddle, working as a dishwasher at Corby Hall when I was in high school. Still, conscious of my new status as a student, and my fixed status as a townie, I made a show of loyalty, hardly leaving campus freshman year.

Not that we were encouraged to leave campus. Sure, there were community service programs and Wolfie’s runs, but the general impulse to “stay put” reflected a deeper division between town and gown. I’ll always remember bristling at one piece of advice directed to my classmates and our parents as we sat in freshman orientation at the Joyce Center. For our safety, we were told, it was best not to venture south or west of campus — not to cross the river, as it were.

Freshman year, one of my dormmates in Siegfried Hall did cross the river. It was a cold winter weekend. He drank too much off campus. Insisted he knew the way home. Slipped the attention of his friends and ended up in the river’s frigid waters. Amazingly, he made it across, eventually drawing the attention of the South Bend police and enduring all kinds of trouble afterward. But he made it to the other shore. Sadly, others haven’t been so fortunate.

The river endures, heedless of our follies, our misfortunes. But while the St. Joe put South Bend on the map, the things we once built around its waters no longer require that liquid lifeline. The city’s industrial decline is mirrored in the stagnation of other river cities throughout the Midwest.

But the city and the river remain inextricably bound. One success story highlighted during South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg’s presidential campaign was the installation of “South Bend River Lights” downtown. This glowing display reimagined what the river could be, putting an old source of prosperity to new use, wowing walkers and tourists.

Even Notre Dame has ventured from its own familiar shores to embrace the river’s reinvention. Not far from where the “River Lights” dance, South Bend and the University have partnered to build an underground hydropower facility. Once it’s complete, the river’s current will spin turbines, generating power to light campus.

Not a single drop of the river will make its way up to the lakes, of course. But the river will flow by nonetheless, silent and steady, electron by electron, deepening the connection between two separate shores.

James Seidler is a writer living in Munster, Indiana.