On pages of yellowed notebook paper owned by a Notre Dame professor are lines of elegant cursive reminiscent of a past era. Some detail the content of a 1930s biology or English course at Notre Dame — covering subjects like the properties of cholera or the epic poem Beowulf.

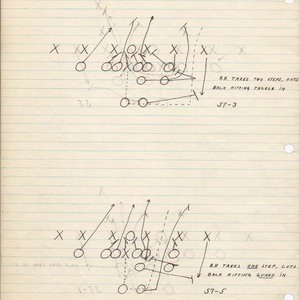

Beyond those pages is something different. Clusters of X’s and O’s are accompanied by a more succinct script: “R.H. takes one step, cuts back hitting guard in.”

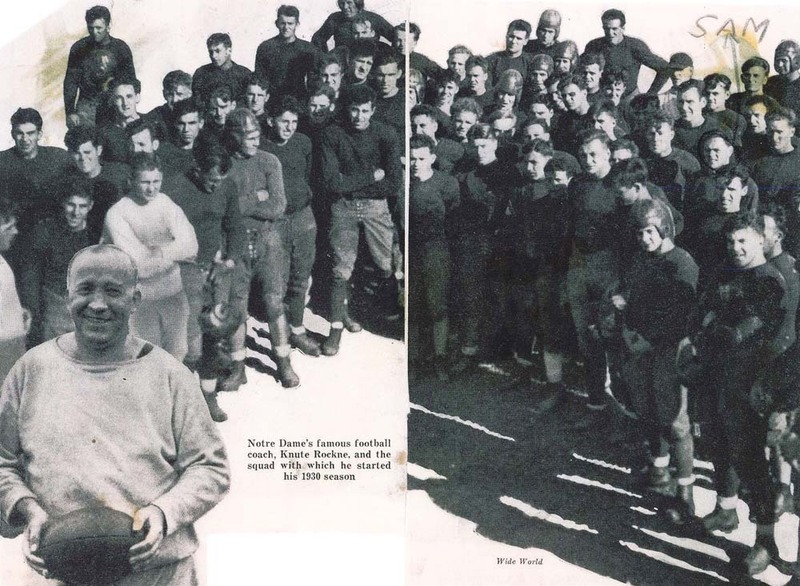

. . . “A smart coach spends his time on fundamentals.” These are among the recorded plays and takeaways of Ben Kane, a member of the 1930 freshman football team, the last of the Knute Rockne era.

Kane was born in Philadelphia on April 15, 1910, and grew up in Chicago. After a successful career as right halfback at Marshall High School, he was recruited and offered a football scholarship to play at Notre Dame. “That was the highlight of his life at that point,” says Larry Kane, the eldest of his two sons, who adds that his father knew all about Notre Dame from its storied gridiron record during the 1920s, especially its famed Four Horsemen backfield.

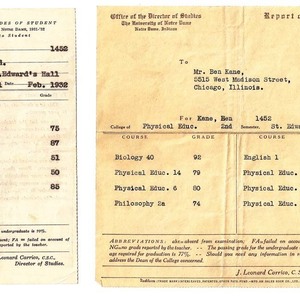

One of Notre Dame’s few Jewish students at the time, the elder Kane enrolled in 1930 as a physical education major — a program criticized as giving athletes an easier workload. Rockne, a professor of physical education among his other roles, was naturally an advocate of it. But to maintain it, the University strictly required that P.E. majors take nonmajor courses. Rockne’s athletes, “unlike their Big Ten counterparts, could not avoid most of the difficult classes at their school,” author Murray Sperber writes in Shake Down the Thunder: The Creation of Notre Dame Football.

“It’s clear that he wasn’t a great student, and he failed a few courses,” says Neil Kane, one of Ben Kane’s grandsons and the director of curriculum and capstone advising in the University’s ESTEEM graduate program in technology entrepreneurship. “Although the registrar said he was not kicked out.”

Kane’s transcript shows he took a varied course load that included English, biology, religion and philosophy. He was placed on academic probation during the spring of his freshman year, but remained eligible to return for his sophomore year.

Kane participated in more than football. In his playbook, he also penciled in notes from basketball practices under coach George Keogan. “Dribble in basketball is an art,” he wrote. “Coaching is a matter of individual perfection of every player as a team.” But the ultimate dream was to play Notre Dame football, especially as a kid from Chicago.

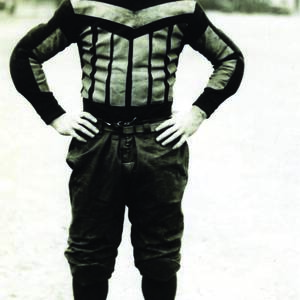

The freshman football team was coached by Manfred Vezie ’29, ’31J.D., and William Jones ’28, ’31J.D., according to the 1930 Official Football Review. That year, the guide reports, some 287 “high school heroes” tried out for the squad, but only 85 earned the coveted spots. In those days, the freshman team “underwent a thorough initiation into the intricacies of Notre Dame football,” introducing players to the “Rockne system” as they vied for places on the varsity depth charts.

During the 1930 season, Rockne held daily meetings in the Lemonnier Library, now Bond Hall. Kane talked about them in an interview he gave late in his life to the Chicago Tribune. The freshmen were among the first players to run out onto the field at Notre Dame Stadium, which opened that fall.

The sudden death of the famed coach in a plane crash on March 31, 1931, shocked Americans, particularly the college football world, but the news took a full day to reach most students on campus. “The story my dad told is that everybody thought it was an April Fool’s joke; no one believed it,” Larry Kane says.

His father, like so many others, revered Rockne. “Any one of those people would have given their life for him,” Larry says. Ben Kane was one of countless players and fans left devastated by the coach’s death, but it also put his future at Notre Dame in limbo.

Kane attended a second year at Notre Dame, but left the school after spring 1932. Rockne had controlled the distribution of scholarship money in the football program, and his death, alongside the worsening economic depression, meant money was scarce. Though the Kane family does not know whether a loss of football scholarship led to Ben’s departure, an archived promissory note shows an unpaid bill of $144.98 in his name, due to the university in August 1932.

He never returned to Notre Dame as a student. Despite that, Kane proudly carried his identity as a Notre Dame football player the rest of his life.

He later received a scholarship to play football at Northland College in Ashland, Wisconsin, but left that school, too, without earning a degree. He returned to Chicago in the late 1930s to launch Benny Kane’s Bar-b-Kue, for years a local favorite on Independence Boulevard on the city’s west side.

Kane was well-known in the neighborhood not only for his food, but also as a football player. Everyone knew him as a Marshall star who went on to play at Notre Dame. It was “the anchor point of his entire life,” Larry Kane says. “He didn’t just talk about Notre Dame every now and then, he talked about it all the time.”

He shut down the restaurant during World War II to join the war effort by working in a defense plant. After the war, he opened Norshore Camera.

In 2006, Ben Kane visited campus with his younger son, Scott, for the Stanford game. “It was an amazing moment for him to come back and feel, not just the pride of having been there, but you know, be the center of attention for a minute again,” Neil Kane says.

In a photograph taken that day, Ben is smiling in a gray crewneck sweatshirt with Rockne’s image on it. Behind him stands another man. “Do you know who that is?” Scott Kane asks. “That’s Jack Rockne.” Upon hearing of Ben Kane’s upcoming visit, the Alumni Association office had arranged for Knute Rockne’s youngest son to meet him.

From saving old notebook pages describing football plays, to being “plastered to the TV” in Larry Kane’s words every time the Fighting Irish played, Ben Kane was dedicated to Notre Dame. Before his death in 2007 at age 97, he requested that his family bury him with a Notre Dame football.

His playbook is now held by Neil Kane, who received it from his uncle Scott after he began working at Notre Dame in 2021. Taking a job at the University where his grandfather attended was coincidental, Neil says, but the renewed Notre Dame connection prompted a further look into the notes and plays that Ben Kane left behind.

“As soon as I got here, my uncle was quick to say, ‘Oh, your grandfather would have found this such an amazing story,’” Neil Kane says.

Kate Ross, a senior American studies major and journalism minor, was this magazine’s summer intern.