Though she knew the call could come at any time, it was still a shock. “Are you Madame Jeanne Ardin, daughter of Marc Ardin?”

“Yes, this is she.”

“This is Claudia Louis, with Exit. I am phoning to let you know your father has decided to end his life next Tuesday morning.”

Exit is one of a growing number of organizations that helps its members arrange legal, medically assisted suicide. Based in Switzerland, with a membership of more than 145,000 people, Exit receives about 3,500 requests annually for assisted death. In 2022, they approved about 1,300 of these requests and facilitated 955. Marc Ardin’s was one of them.

Marc was also my father-in-law. Jeanne is the elder sister of my wife, Saskia. As of 7 p.m., April 5, 2022, we had six days to come to terms with Marc’s decision.

Medically assisted suicide is an increasingly common phenomenon around the globe. As more people are outliving the health of their minds and bodies — often incurring ruinous financial costs in the process — the notion of ending life in a time and place of one’s choosing has become more appealing. In addition to Switzerland, medically aided death is now legal in 10 other countries, including Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Spain. Switzerland has the longest-standing custom of legal suicide in the world. Since 1942, Swiss law has permitted self-administered death as long as the individual’s motives are deemed “altruistic.”

The United States has had a contentious relationship with medically assisted suicide. Ten states and the District of Columbia now have legally protected, medically assisted right- to-die programs. On November 22, 1998, the television news program 60 Minutes broadcast a video of Michigan physician Jack Kevorkian — aka “Dr. Death” — while he performed voluntary euthanasia on Thomas Youk, a 52-year-old man with advanced amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease. As this was in violation of Michigan law, Kevorkian was convicted of second-degree homicide shortly thereafter and spent more than eight years in a state prison before being paroled by then-Governor Jennifer Granholm.

Four years before Youk’s death, voters in the state of Oregon passed the nation’s first so-called “death with dignity” law by ballot initiative with a scant 51 percent majority. Three years later, after legal efforts to derail its implementation, voters affirmed the law by a larger margin days after it took effect. In most of the other states that have approved the procedure, laws have been court-ordered or enacted since 2016.

Medically aided death rules differ sharply among jurisdictions. Variations in who decides, qualifying medical circumstances and the ways death can be administered are stark. In Vermont, eligible candidates must have an irreversible illness with no more than six months left to live. As in Switzerland, they must also be able to ingest lethal substances on their own — the critical difference between suicide and euthanasia. In Canada, candidates may be as young as 18 and need not have any life-threatening illness. Canadian physicians can also administer intravenous sleeping agents and fatal barbiturates directly, without the patient’s help. This year, Canada’s assisted death laws were scheduled to provide greater flexibility for those with mental illnesses, including some who are incapable of making decisions to die on their own. That move has been delayed until next year, pending further study. A growing number of Canadians are opting for suicide because they are poor or can’t find enough to eat or afford to live the way they want.

Canada appears to be sliding down the long-feared slippery slope, where well-intended assisted suicide rules gradually morph into a form of state-sanctioned eugenics. In 2021, over 10,000 Canadians ended their lives through state-approved euthanasia, accounting for 3 percent of all deaths in the country that year. In the state of California — a jurisdiction with a population similar to Canada’s but with more stringent right-to-die laws — only 486 people did. Since California’s End of Life Option Act became law in 2016, assisted suicide has accounted for about one-tenth of 1 percent of all Californian deaths.

To call Marc Ardin stoic understates his imperturbability. For years, progressive polyneuropathy robbed him of feeling and function in his extremities. In addition to chronic numbness and progressive muscle loss, disfiguring scoliosis had visibly diminished him. Six feet, 4 inches tall in his prime, by his 93rd year he was only 5-foot-7 when perched upright, precariously, on his four-wheeled walker. For decades he had fought back the paralyzing effects of polyneuropathy by pedaling his stationary bike daily and taking brief, shaky walks outdoors, weather permitting. Though in constant pain and increasingly immobile, he never once complained.

Like many Swiss men of his generation, Marc was emotionally distant. Calvinists are known to prize austerity and humility over lush comforts and braggadocio. In the decades that followed the St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre of 1572, when vengeful Catholic mobs and assassinations of Protestants led waves of Huguenots to flee France en masse for the Swiss city of Geneva, John Calvin instructed his flock to manifest their gratitude to God through hard work and service to their neighbors. Marc personified this ethos. No one doubted his loyalty and generosity, least of all his daughters, in-laws and grandchildren. He built upon the commercial achievements of his parents and grandparents, attaining financial success that he never looked upon as his own but rather as the providence of his children and their children beyond. Marc above all was dutiful.

Emotional distance marred his most intimate familial relationships. His 40-year marriage to Janet Schott-Ardin — my mother-in-law — ended in divorce. His eldest daughter, Jeanne, was a frequent target of his harsh criticism and unfair judgment. My wife, Saskia, always sided with her sister in these senseless disputes. Three days before he ended his life, Marc told Jeanne they had never had any relationship, a remarkably insensitive charge that devastated her.

In an effort to break the cycle of generational damage, Jeanne worked hard to understand why her father treated her and others with recurrent, emotional disdain. She learned he was unloved as a child, often left for hours locked out on a balcony overlooking a garden while his parents and house caretakers attended to other affairs. Having never received much love and warmth from his parents, he had diminished facility to bestow it.

Marc’s membership in Exit was no secret to his closest relatives and friends. He often mentioned it during our visits to his nursing home in Nyon on the banks of Lake Geneva. The Exit program was tailor-made to his beliefs. Unlike Dignitas, the flashier Swiss association, Exit was open only to Swiss residents, and mostly comprised of decadeslong members. Dignitas accommodates foreigners and can be accessed quickly by almost anyone who — like ex-Studio 54 club owner Mark Fleischman last summer — can afford to travel to Switzerland and pay its high fees. In contrast, Exit’s end-of-life program costs nothing and is normally accessed with complete discretion.

Exit provides end-of-life services only to members who have hopeless prognoses, unbearable symptoms or unacceptable disabilities, specific due-diligence criteria that have been negotiated in a bilateral agreement with the canton of Zurich, where Exit is headquartered. Additionally, the person wishing to die must know what he or she is doing (faculty of judgment); not act on impulse (due consideration); have a persistent wish to die (constancy); not be under the influence of any third party (autonomy); and be able to die by their own hand (agency). This means that patients with mental illnesses, including dementia and Alzheimer’s, are seldom eligible for Exit’s services because they have lost their faculty of judgment and agency. No one acting on depressive impulse may receive Exit’s help, either.

As one of Exit’s certified end-of-life attendants, Claudia Louis had significant experience in helping members achieve their precise end-of-life wishes. She and Marc’s doctor confirmed he had met Exit’s five principles. They also understood he did not want to be a burden to his family.

But Louis prevaricated when Marc’s desire not to be burdensome seemed to take on an extreme dimension. Marc did not want his family members — including his American Catholic son-in-law — to try to talk him out of his decision. When Louis arrived in Marc’s hospice room on the afternoon of April 5 for a final consultation, he was very disappointed she had not brought “the magic potion,” as he called it, to end his life. He expected to die that day, without informing anyone but his medical team beforehand.

That discussion became quite heated. Louis spent more than an hour patiently but persistently trying to convince Marc that his decision not to inform at a minimum his own two daughters could have lifelong, unintended, scarring consequences. Notoriously stubborn, Marc refused repeatedly before acquiescing, grudgingly.

But for the flash of searing pain Jeanne experienced when her father said they had no relationship, the six days that followed Louis’ phone call can best be described as precious. They included heartfelt letters from his four grandchildren, many moments of profound emotion punctuated by grace, sacred moments of prayer and harmony — and in the end, an unexpected, transformational reconciliation that allowed Jeanne and Saskia to know they were deeply loved by their father in ways he had never expressed before.

“Cher Grand-Papa — I not only support your decision, I also have great respect for the approach you are taking. I have always seen you as a man of great dignity who never wanted to disturb others with your health. I understand you want to maintain this dignity, rather than disappear slowly. Your memory and values are deeply instilled. They will last long after your departure.”

“Dear Grandpapa — I do not know where to begin thanking you. You have shaped many parts of my life and embody virtues I aspire to emulate. Your love and support have always been apparent to me. The impact you have had on my life far exceeds what you are willing to take credit for.”

“Dear Grandpapa — I want to say I will miss you greatly. All my visits to Switzerland were enriched by the moments I spent with you. I loved hearing your life stories and how you saw the world — even if you couldn’t figure out what 5G is. You exemplify devotion to family. I am filled with enormous love and respect for the man I am lucky enough to call my grandfather.”

I hoped Marc would retain hope in his creator for all he had not yet seen. I also realized his death would be a spiritual lesson for those who loved him — inspiring, perhaps, as my mother’s was, or dispiriting, as my father’s turned out to be. Death is not just a personal experience. It impacts one’s loved ones profoundly.

Catholic teaching on suicide is categoric. Its firm rejection has scriptural foundation in Genesis, which prohibits the shedding of innocent human blood. The stories of Saul, Ahithophel, Zimri and of course Judas Iscariot all reveal how self-killing can involve utter alienation from God. In the Acts of the Apostles, St. Paul famously intervenes to stop his own jailer in Philippi from killing himself. “What must I do to be saved?” the jailer implores him. “Become a believer in the Lord Jesus,” Paul replies, “and you will be saved, and your household, too.”

Early Christian rejection of suicide was partly a reaction to its historic glorification and absence of theology. Post-Homeric Greek society was broadly tolerant of suicide, even encouraging it for those who were sick, guilty of egregious crimes or responsible for military defeats. Though Plato opposed suicide, notably objecting to Socrates’ acquiescence to drink hemlock per his death sentence, the Roman aristocracy and intelligentsia often resorted to suicide to preserve honor, demonstrate patriotism and fidelity, or atone for personal shame. The suicides of Cato, Brutus, Marc Antony, Cleopatra and Seneca were all glorified in their day. The Stoic philosophers of the era urged suicide as a rational expression of dignity and honor.

Early Christians objected to these practices as well as to related cruelties like public shaming, the apex of which was crucifixion. In The City of God, St. Augustine argues that no one has the right to kill a guilty man, let alone an innocent one, including himself. “We rightly abominate the act of Judas . . . since he despaired of God’s mercy and in a fit of self-destructive remorse left himself no chance of a saving repentance.” Augustine specifically condemned suicide as lacking the virtue of fortitude. He believed suffering should be endured through unwavering Christian faith, hope and charity.

With all these precedents, canonical and ecclesiastical condemnation of suicide became entrenched. The councils of Nimes, Orleans, Braga and Auxerre all denied Christian burials to those who killed themselves. In his Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas Aquinas stated that “it is altogether unlawful to kill oneself . . . because life is God’s gift to man and subject to His power, Who kills and makes to live. Hence whoever takes his own life sins against God.”

In sum, suicide is contrary to Catholic theological and moral teaching. In addition to fortitude, it is seen to violate the principles of charity, justice, proper self-love, the common good and the additional demands of a proper relationship with God, our maker. In a 2012 article in the Notre Dame Journal of Law, Ethics & Public Policy, Father Robert Barry, O.P., argues persuasively that continued support for the Catholic prohibition on assisted suicide is essential to protect the most vulnerable among us from harm. The slippery slope we are now seeing in Canada bears witness to Father Barry’s prescience.

Like his grandchildren’s letters, my oral and written communications with my father-in-law in the last week of his life were supportive and filled with gratitude for all he had done. “Supporting you in this profound moment has nothing to do with my beliefs, what is right for me or my personal conception of God,” I wrote. “My religion instructs me not to judge anyone. It also tells me to support others, even if they see the world differently than I do.”

As a practicing Catholic, however, I was unable to extend any certitude to his personal relationship with God. “While no human being is your judge, Marc, the same cannot be said with certainty about God. The truth is, we don’t know what ‘He’ thinks. This is why we call it ‘Faith.’ Like any relationship, the strength of one’s relationship with ‘the man in the sky’” (Marc’s chosen term for God) “depends upon how much time and effort has been put into it over the years. All relationships require work and hope and forgiveness and love to thrive.”

I wrote my letter to Marc in English even though he was a native French speaker. As human beings count and pray almost exclusively in their native languages, I concluded my letter with three prayers in French: first, Psaume 23, the “Shepherd’s Prayer”; next, Je Vous Salue Marie, the Hail Mary; and finally Notre Pere, the Our Father. “For thousands of years, billions of people who have believed in God as I do — that is to say, other devout Jews and Christians — have relied upon three prayers to communicate to their Mother and Father in Heaven,” I wrote passively. “You too may find that reflecting on these three prayers brings you special comfort.”

As it happened, Notre Pere were the very last words Jeanne, Saskia and my father-in-law recited together.

My personal journey with my father-in-law’s decision was different from that of his daughters and grandchildren. While I wanted him to feel my support, I also hoped his process would enhance his understanding of and relationship with God. I did not want to be a complicating presence in the last week of his life, but neither did I want to dilute the profundity of his agency and actions.

The medical definition of a good death is rather sterile. Such a death should be, it is said, free of avoidable distress for the patient and their family and in reasonable accord with the patient’s wishes. Clearly a beautiful spiritual death involves more: deep gratitude for the gift of life one has been given, and genuine awe for the world yet to be revealed.

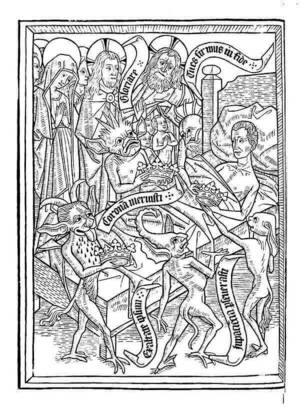

Dominican friars are credited with writing the Ars Moriendi — The Art of Dying — early in the 15th century. The Black Death had ravaged Western Europe and North Africa decades earlier, killing as much as half of the population, including most of the clergy. The primary purpose of Ars Moriendi was to console those who were facing their mortality alone, assuring them death was nothing to be feared. It also outlined five temptations that often conspire against a fearless parting, namely a lack of faith, despair, impatience, spiritual pride and avarice.

As one who has often felt the redemptive power of God’s grace, I did not want Marc to lose sight of all the wonder and joy and light that filled his life and the possible beauty in his new life to come. I saw my task as helping him remain open to receive grace and wisdom and divine acceptance. Ralph Waldo Emerson said, “All I have seen teaches me to trust the creator for all I have not seen.” I hoped Marc would retain hope in his creator for all he had not yet seen. I also realized his death would be a spiritual lesson for those who loved him — inspiring, perhaps, as my mother’s was, or dispiriting, as my father’s turned out to be. Death is not just a personal experience. It impacts one’s loved ones profoundly.

After Jeanne and my wife finished praying with Marc, they left the room, and his doctor came in. The doctor kindly provided the following chronology of Marc’s last moments.

Before drinking, your father looked outside and said, “I’m lucky.” After a brief pause, he continued to speak.

“I see this beautiful lake. I have sailed there all my life — in rowboats, motorboats and sailboats.”

“It is a beautiful day.”

He then drank the glass that was handed to him by the attendant, quietly and peacefully.

“That really tastes awful!”

He then picked up a waiting coffee cup, drank its contents and looked out the window one last time.

“My, this coffee is delicious!”

A few seconds later, he looked at us and said, “I hoped for a faster effect from your potion.” His eyelids then grew heavy. He closed his eyes. A few seconds later, he spoke his last words. “I want to thank my daughters.”

I took his hand in mine as his breathing became light and more spaced out. Eternal sleep then came and took him to where he said he wanted to go. It was all very sweet and beautiful.

Dear Jeanne, dear Saskia — I hope these last moments of your father’s life will be a beautiful memory for you, just as they are for me.

Professionally administered, medically assisted death programs strive to achieve a particular outcome: death with dignity. My father-in-law’s experience with Exit appears to have achieved more than this.

Because of Claudia Louis’ insistence, Marc Ardin’s immediate family members got to share intimate feelings and expressions of gratitude with their father, grandfather and father-in-law that would have been otherwise left unsaid. These heartfelt exchanges led to a sense of communal belonging and closure that brought us all great comfort.

Contrary to what Catholic doctrine states, Marc and his family experienced fortitude, charity, justice, mutual love and a sense of the common good in ways we never dreamed possible. Jeanne and Saskia got to hear and feel their father’s love as never before, helping to heal a deep wound. Now when they think of their father’s death, both feel profound gratitude and lasting peace, without forgetting his shortcomings. Marc’s decision elevated our understanding of the common good, sparing others a prolonged decline.

In the end, Marc experienced grace and reconciliation with those he loved. Through prayer and devotional reflection, he deepened his relationship with “the man in the sky.” Because of the expert care of Claudia Louis and the deliberate steps Exit encouraged him to take, Marc undoubtedly died with dignity. He also left this world with a heightened sense of divinity and unprecedented love for his family.

It is now projected that by 2050 the U.S. government will spend more than $1 trillion a year on millions of institutionalized Americans who will suffer from advanced stages of dementia and Alzheimer’s. To put this in context, $1 trillion is 50 percent more than all federal, state and local agencies spend today on K-12 public education.

As more and more members of the human family outlive their mental and physical capacities, maintaining dignity and heightened divinity within grace-filled, loving communities will become more difficult. Let us pray we will find the most beautiful, holy outcomes — now, and at the hours of our death.

Terry Keeley was one of the University’s first young trustees and today sponsors the annual Keeley Vatican Lecture hosted by the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. His article about Wall Street’s role in the 2008 financial crisis, “Eye of the Needle,” won the Best General Essay award from the Catholic Press Association in 2010.