The Notre Dame Boat Club on St. Joseph’s Lake in the 1890s. University of Notre Dame Archives

The Notre Dame Boat Club on St. Joseph’s Lake in the 1890s. University of Notre Dame Archives

Father Thomas E. Blantz, CSC, ’57, ’63M.A. begins at the beginning.

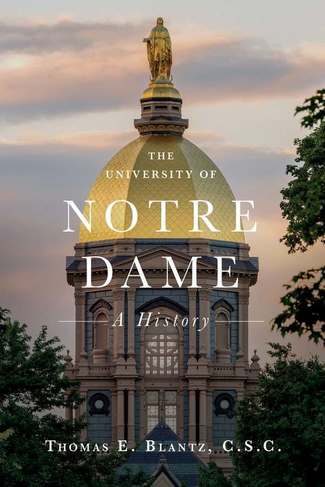

In The University of Notre Dame: A History, published in August by Notre Dame Press, he spares his readers the long, theoretical introduction customary to academic history. Instead he launches with a theme-setting story: Father Edward Sorin commenting appreciatively that his conspicuously English first name carried no “vestige of nationality.” That blessing allowed annual campus celebrations of Sorin’s patron saint’s feast day to serve as yet another sign that the school he founded in the Indiana backwoods was to be wholly Catholic and wholly American from the start.

The author of three books, Blantz has lived a significant portion (but keeps himself out) of the history he writes about, an arc that stretches from undergraduate student who arrived in 1953 to professor emeritus of history today and spans graduate studies as well as administrative work in residence halls, the archives and the Main Building. Along the way, he acquired sensitivity to the needs of readers, noting his book’s short preface and tidy conclusion with the inauguration of Father John I. Jenkins, CSC, as University president in 2005. “I thought they were sufficient,” he says of largely bypassing those traditional elements in a volume that weighs in at 605 pages. “I did not want the book to be impossibly large.”

When did you decide to research and write this book?

As I approached my 80th birthday, I decided it was about time to retire from teaching, after 46 years. I knew I wanted to keep intellectually alive and I decided to try to learn whatever I could about the history of Notre Dame. I had some background for it: I had spent more than 50 years here as a student and teacher; I had served as University archivist for about 10 years; and for a few years I had offered an undergraduate research seminar on the history of the University. When I started, I did not know if the research would result in a series of articles, a book or just a pleasant hobby.

How long did it take you, and what kept you inspired?

I suppose I was working on this for about six years, not necessarily full time. I have always enjoyed history. I enjoy learning more about it, I enjoyed living and serving here all these years, and I respected what Notre Dame was doing. I found it very satisfying to learn more about it.

Any surprises along the way?

One surprise for me was to learn how difficult it was to begin a college in the mid-19th century. One historian of American education noted that there were approximately 250 colleges in the United States in 1860, but perhaps another 700 had been started and failed. He also stated that between 1850 and 1866, 55 Catholic colleges were founded but 25 of them were abandoned by 1866. It was a serious challenge for those early Holy Cross religious.

What were the hardest parts for you to research and to write?

The most difficult part was probably the growth and development of the academic side of Notre Dame. The center of a university is in its teaching. Successful teaching often depends on the personality, motivation and enthusiasm of the teachers, and these are not easy to quantify and write about.

Did any episodes open up that seemed to you promising for further exploration — projects for other scholars or even current students?

I can think of several areas which could merit further research and study: the work of the Holy Cross Brothers at Notre Dame through the years, the work of the Holy Cross Sisters at Notre Dame through the years, the important presidency of Father Thomas Walsh (1881-93), Brother Leo Donovan and the Notre Dame Farm, the School of Agriculture (1917-32) and many others.

You enter the Notre Dame story in the 1950s, soon after Father Hesburgh becomes president, even if you don’t appear in the narrative. Did you find your life at Notre Dame a help or a hindrance in organizing and interpreting the University’s modern era?

I thought my presence here and my firsthand experience of the University was a benefit in telling the story. I knew the personalities of some of the people involved; I understood the decisions that I was a part of; and I remember conversations that were not in the public record. I lived through and was part of those last 50 years, and that was a help. . . . I can add that I might have been able to understand the issues from the different constituencies’ points of view better since I had been a part of each one myself.

You’ve written book-length biographies of important but perhaps lesser-known Catholic figures in the 20th century. How did that interest in people shape your approach?

I guess I am slightly more interested in persons than in movements or happenings, but I think most people probably are. We can all relate to other persons and try to understand them since we are like them in so many ways.

Presidencies seem to be the most salient organizing principle in your account. Why?

As an historian, I wanted to organize it chronologically, I am very interested in people, and these 17 or 18 presidents helped to shape the book into about that many chapters. And each president does have an important influence on the University during that particular period, setting the tone for that period.

What did you learn about Notre Dame — big picture lessons?

I learned that Notre Dame has changed greatly through the years in the level of education offered, in the quality of the education offered, in the physical expanse of the campus, in the composition of the faculty and in so many other ways, but the mission has been the same: to educate young persons in mind, heart and soul to be the better persons they can be.

Interview by John Nagy, managing editor of this magazine.