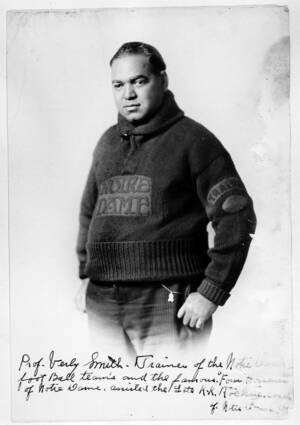

Verly Smith was a dashing man, good with his hands, an entrepreneur, a family man, a gambler who drove big cars, wore stylish hats and enjoyed a good cigar.

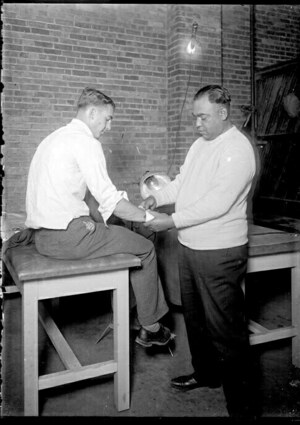

A part-time trainer for coach Knute Rockne’s football teams from about 1924 to ’27, Smith worked other jobs in South Bend at the time, all while preparing to open his own downtown gymnasium. Hired to heal the muscle strains and other injuries of Rockne’s players — records indicate Smith was probably Notre Dame’s very first African American employee — he also took on trainer duties for the basketball, track and baseball teams.

Flashy. That’s the word that comes to mind as two of Smith’s grandsons — Bruce Smith, 80, of San Antonio, Texas, and Craig Smith, 72, of St. Charles, Missouri — describe their grandfather.

Bruce was only 6 years old and Craig wasn’t yet born when Verly Smith died. But while they were growing up, they heard colorful family stories about him. He liked to “wear a suit with a vest,” Bruce Smith says. “He was fun and flamboyant. People liked to gather around him.”

The patriarch, whose son Alfred would follow his path some 30 years later as an Irish athletic trainer, was well known about town, a savvy businessman whose ventures received regular mention in local newspapers throughout his life and career.

Verly E. Smith was born February 6, 1886, in Attica, a small town near Lafayette, Indiana. Little is known about his childhood. One family story goes that as an infant Verly was given to another family to raise. Another version says he spent his early years in an orphanage and was adopted at about age 7. George Douglas and Emma (Revels) Smith raised him, according to ancestry records. In 1900, the family was living in Lorain, Ohio.

By 1905, the young man had moved to South Bend and was listed in the city directory as a musician living at a rooming house. Census records show he was a drummer.

In September 1909, Smith, then 23, married Ethel Lucas, 27, in South Bend. It was a second marriage for the bride, who already had two children, Nellie and Harold. Verly Smith would raise those children as his own in addition to the five the couple had together: Verna, Alfred, Dewight, Wilma and Marian.

Within a year, the family was living on West Colfax Avenue, where Smith operated The Coterie Club, a nightclub and café. He was doing quite well for himself. The October 1, 1910, Indianapolis Recorder, a Black newspaper that covered statewide news in African-American circles, noted that Smith had just purchased an Empire automobile made in Indianapolis. “He has the distinction of being the first colored man” in South Bend to own a car, the newspaper reported.

By 1915, Smith and his growing family had moved to Benton Harbor, Michigan. City directories and his World War I draft card indicate he owned a hotel and a restaurant. Five years later, he was listed as a masseur at a bathhouse. Craig Smith says his grandfather ran sports camps in Benton Harbor, drawing customers from Chicago who took passenger ships to resorts on the eastern shore of Lake Michigan.

In later years, Smith was described in newspaper stories as a former trainer for world heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey. Smith’s initial connection with Dempsey isn’t clear, but the two men may have met in 1920, when Dempsey traveled to Benton Harbor to defend his title against Billy Miske before a crowd of more than 11,000 spectators. The champ knocked out his challenger in three rounds, and retained the title for six more years.

In the early 1920s, Smith was hired as a trainer for the Notre Dame football team. His grandsons don’t know how or when he first met Knute Rockne, or whether it was Rockne who offered the job, but Smith was the team’s trainer during the height of Rockne’s coaching career, including in 1924 — the season of the Four Horsemen, the famous Irish backfield. By 1926, the family had moved back to South Bend and made their home at 1002 Campeau Street, a few blocks south of campus.

Few references to Smith appear today in the University Archives, and he wasn’t listed among the team’s staff in football programs or editions of the Notre Dame Football Review, but Smith’s role at Notre Dame was widely known, and he was frequently mentioned in South Bend Tribune reports of that era.

Meanwhile, Smith also served as a trainer for the South Bend YMCA basketball league, the South Bend Central and Mishawaka high school football teams, and the Athletics, a baseball team fielded by the Studebaker automobile factory. High school athletes were safe “under the skillful eye of Verly Smith, famous master of bruises and wrenches,” the Tribune reported.

In June 1926, while he was still working at Notre Dame, Smith opened an office downtown in the LaSalle Hotel Annex and offered athletic training and massages to businessmen. “His attention is not needed at the university during the summer months,” the newspaper explained.

Later that year, he opened a commercial gym at 228 South Michigan Street. Members would stop by to exercise, relax in steam baths, smoke cigars and get rubdowns for their aching muscles. It was advertised as the Verly Smith Health and Body Building Institute.

Rockne endorsed Smith’s new venture. The Notre Dame trainer “knows his business very thoroughly and I believe that any business man who will give him a little time will find it very, very much worth while. . . . I have looked over Mr. Smith’s establishment and I recommend it very highly to anyone who is interested in health,” Rockne wrote in a 1926 letter that survives in the University Archives.

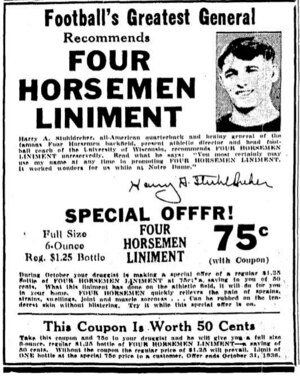

Smith left his job at Notre Dame by fall 1928. During the Great Depression, he began making and selling a product called Four Horsemen Liniment, an ointment to relieve sprains and sore muscles.

“During the time I was at Notre Dame as trainer,” Smith told the Tribune in 1932, “I perfected the formula. It was a further improvement on one I had discovered and used successfully while trainer in Jack Dempsey’s camp. It was in regular use during the height of Notre Dame’s victorious regime under Knute Rockne.”

“Used and endorsed by the Four Horsemen of Notre Dame” read a statement on the blue and gold label, which featured a drawing of Notre Dame’s famous foursome. Bottles still show up on eBay and other online auction sites, and a rare Four Horsemen Liniment bottle and box are held in the University Archives.

Smith liked to gamble at times. Family lore says he offered the licensing rights to Four Horsemen Liniment as his part of a wager — and lost, Craig Smith says. Nevertheless, the wily operator continued to make and sell his product under another name.

Smith was active in the Black community, leading a committee that planned an annual “emancipation celebration” at Berrien Springs, Michigan, during several summers in the mid-1930s, the Tribune reported.

One son, Alfred Augustus “Red” Smith, born in 1912, was an outstanding football player. An Indiana all-state high school athlete, Red later played for Wilberforce University and West Virginia State College, and in the 1930s for the Brown Bombers, a professional team based in New York City. The Bombers are considered the most important all-Black football team of the era when segregation still ruled in professional sports and in much of society.

His playing days behind him, Red Smith worked as a trainer for the Notre Dame football, basketball and track teams in the late 1940s to mid-’50s, during the years of head coaches Frank Leahy and Terry Brennan. “He learned his training techniques from his Dad,” Bruce Smith says of his father. Red also was head football coach at South Bend Central Catholic High School during the 1950s and a trainer for professional boxer Archie Moore, the world light heavyweight champion. He died in 1990.

Bruce Smith says Notre Dame paid his father and grandfather in cash. It’s not clear why, but the grandsons theorize that in those days some University officials were uneasy about having Black employees on the official athletics payroll.

“They were very dedicated to Notre Dame,” Bruce Smith says of his father and grandfather. They both enjoyed working with student-athletes, and they knew their work was important.

The Smith family is connected by marriage to William H. Alexander Sr., believed to have been the University’s first full-time Black employee. Alexander worked at Notre Dame from 1934 to ’62 as a residence hall porter and campus mailman.

Ethel Smith, Verly’s wife, died in 1938. By 1940, the widower was living in Niles, Michigan, still selling the liniment — and still attracting headlines. “TRAINED THE ‘FOUR HORSEMEN’” read one above his photo in the July 20, 1940, edition of the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper.

Later that year, Smith moved to Culver, Indiana, where he met and married Alma John Floyd. Together they ran a health farm and poultry business. Verly also worked at nearby Culver Military Academy.

The flashy trainer of the Rockne era passed away suddenly on May 3, 1948, at age 61. He was laid to rest at the Masonic Cemetery in Culver.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Contact her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe.