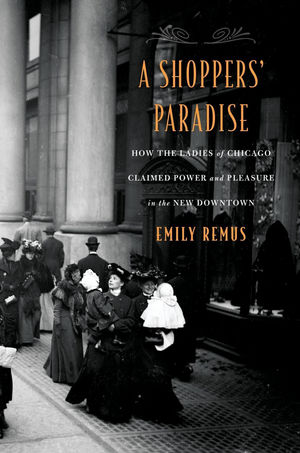

Marshall Field’s in Chicago attracted crowds of shoppers who clogged sidewalks and inspired calls for a “retail curfew.”

Marshall Field’s in Chicago attracted crowds of shoppers who clogged sidewalks and inspired calls for a “retail curfew.”

Emily Remus grew up in suburban Chicago and remembers childhood visits to the city and, in particular, to the famous flagship Marshall Field’s department store.

The grandeur of the 14-story shopping palace awed her, and prompted her to wonder how such places came to be.

It had a lot to do with the consumer economy and the growth of women’s social and economic power in the late 19th and early 20th century, says Remus, a Notre Dame assistant professor of history. She recounts that history in her book, A Shoppers’ Paradise: How the Ladies of Chicago Claimed Power and Pleasure in the New Downtown.

By the 1890s, State Street in Chicago’s Loop was lined with a string of grand department stores: Marshall Field’s, Carson Pirie Scott, Schlesinger & Mayer and The Fair, among others. The department stores added tea rooms, fashion shows and other amenities to attract women.

“It transformed what had been the necessary burden into an activity of leisure,” Remus says. That was particularly true among ladies in the upper classes, who in that era began to wield the majority of consumer spending power. “People are spending more and more of their money as a way of showing their status and affluence,” the author says.

Those efforts to attract shoppers didn’t extend to African-American customers, who often were refused service or provided with deliberately poor service, Remus writes.

As department stores were growing and attracting more women shoppers, the crowded Loop itself was still primarily oriented toward business and industry. Conflicts arose.

“Window design becomes a major new way of advertising and merchandising,” Remus says. As window shopping became popular, some civic leaders suggested that women shouldn’t be blocking the busy sidewalks. At one point, there was a proposal for a “retail curfew” — women should finish their shopping and go home by 3 p.m. to reduce congestion during afternoon rush hour, Remus writes.

The rise of the female consumer also brought about controversy concerning women’s fashions. In 1893, the year the World’s Columbian Exposition was held in Chicago, rumors swept the city that a “pestilence” from the 1860s might return: hoopskirts. The voluminous skirt style would clog the sidewalks and reduce seating space on streetcars, according to critics. A Chicago Tribune editorial called for the creation of an anti-hoopskirt society. (A similar controversy raged about tall, ornate hats that women wore to the theater and opera, blocking the view of other patrons.)

In her book, Remus also details how women started to drink cocktails and other alcoholic beverages in public at tea rooms, soda fountains and other establishments. “It becomes a moral question and a question about what are the boundaries of respectability,” she says. She also covers the Levee (Chicago’s red-light district), prostitution and the problem of men accosting women shoppers in the streets.

The old Marshall Field’s building still stands in downtown Chicago today. It became a Macy’s in 2006 and its retail space is much smaller. Macy’s last year sold floors 8 through 14 to a firm that is renovating the space to lease for offices.

With the rise of online shopping and the decline of brick-and-mortar stores, Remus says a new social revolution is upon us related to consumer behavior. She muses about the “retail curfew” proposal of 1908. “Who could ever imagine today the idea of a city considering a law to discourage shoppers from being downtown at certain hours?” she says.

Americans are entering a very different retail future, according to Remus. “In a lot of ways,” she says, “we’re looking at the opposite problem of what I focus on in the book,” she says.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.