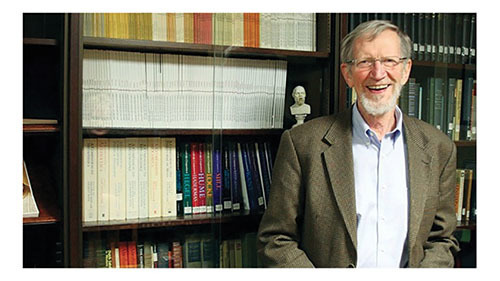

Notre Dame philosopher Alvin Plantinga, whose influential arguments for the existence of God helped redefine the academic debate on the subject, has been named the recipient of the 2017 Templeton Prize. The $1.4-million award from the John Templeton Foundation honors “an exceptional contribution to affirming life’s spiritual dimension, whether through insight, discovery or practical works.”

photo: Calvin College

photo: Calvin College

Plantinga’s insights, developed over a career dating to the late 1950s, reshaped views on philosophical notions like the problem of evil — the argument that an omnipotent and loving God would not allow suffering in the world, therefore that deity must not exist. An all-powerful, all-benevolent God could not prevent evil, Plantinga argues, without also denying humans free will.

He advanced those ideas in a landmark 1974 book, God, Freedom, and Evil. A former Guggenheim Fellow and a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Plantinga’s other works include Faith and Rationality, Warranted Christian Belief and Knowledge and Christian Belief.

Retired since 2010, Plantinga, 84, joined the Notre Dame faculty in 1982 from Calvin College. He will be presented with the Templeton Prize at a September 24 ceremony in Chicago, joining a list of 46 past recipients that includes Mother Teresa, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama.

“The field of philosophy has been transformed over the course of my career,” Plantinga said. “If my work played a role in this transformation, I would be very pleased.”

President Trump appointed Notre Dame law professor Amy Coney Barrett ’97J.D. to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit. Barrett, whose teaching and research focus on federal courts, constitutional law and statutory interpretation, has twice been chosen by students as Distinguished Professor of the Year.

Before joining the Law School faculty in 2002, Barrett clerked for Judge Laurence H. Silberman of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit and for Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia. Her litigation experience as a Washington, D.C., attorney included constitutional, criminal and commercial cases.

As controversial political scientist Charles Murray spoke to about 230 people March 28 inside McKenna Hall, dozens of protestors marched and chanted outside. The event, and the opposition to it, occurred in close proximity but with almost no overlap.

Weeks after Murray’s appearance at Middlebury College turned violent, security was tight for his long-planned visit to Notre Dame at the invitation of political scientist Vincent Phillip Muñoz. A few students and faculty members, Muñoz said, encouraged him to cancel Murray’s visit. He refused, articulating his reasons at the RealClearPolitics website days before the event.

“Given what happened at Middlebury, it would be cowardly to disinvite Murray now,” Muñoz wrote. “Rescinding his invitation would communicate that violence works; that if you want to influence academia, sharpen your elbows, not your mind.”

Murray’s lecture, open only to members of the campus community who had to show Notre Dame IDs to enter, focused on his 2012 book Coming Apart: The State of White America. He outlined his argument that American elites have isolated themselves in a few urban bubbles, creating a dominant economic and political culture that marginalizes the white working class.

The resulting social problems and perceived disdain from the upper classes, Murray said, produced resentment that led to the election of Donald Trump. Murray vehemently opposed Trump but said he offered a way for members of the white working class to express disgust toward elites they consider out of touch with their concerns.

Notre Dame anthropologist Agustín Fuentes delivered an impassioned response as part of the program, charging that Murray offered a nostalgic view of midcentury America unmoored from the political reality that excluded many groups from full participation in society.

South Bend’s Near Northwest Neighborhood has a lead problem. Tests conducted between 2005 and 2015 found that 32 percent of children in the neighborhood showed elevated lead levels in their blood, the highest rate in Indiana.

Lead does not decay; residue remains in dust and soil from long-banned lead paint, a particular problem in this neighborhood with many older houses. “Because we cannot eliminate lead from our living environments, we need to learn how to limit exposure, especially in our children,” said Heidi Beidinger-Burnett, assistant professor in the Eck Institute for Global Health and a member of the St. Joseph County Board of Health.

There’s no safe amount of lead in the body, and accumulating contamination in the blood can cause mental, physical and behavioral problems. Beidinger-Burnett helped organize a community partnership to increase screening among children and educate residents.

During the April 22 “Get the Lead Out” event, Notre Dame graduate students canvassed the neighborhood, providing information on how to minimize exposure and inviting parents to bring children to a free screening at the neighborhood’s community center.

Danielle LaFleur ’17M.A. organized outreach, developing a flyer distributed to more than 600 homes. Students talked to more than 150 residents during the event, and the St. Joseph County Women, Infants and Children program conducted 34 blood tests.

“The information compiled during this project will be used to help our Health Department develop both a short-term and a sustainable plan to address the lead problem in our community,” Beidinger-Burnett said. “It’s a great start to address an important health challenge for all of us.”

For nine years as chair of the Notre Dame School of Architecture, Thomas Gordon Smith established a curriculum focused on the classical tradition. In all, Smith spent nearly 30 years at Notre Dame, retiring as professor emeritus after the 2016 fall semester. His commitment to teaching was rewarded in May with a 2017 Arthur Ross Award for education, presented by the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art.

Smith’s colleague Duncan Stroik also was honored this spring as the recipient of the 2017 Clem Labine Award. Known for his church architecture, Stroik will receive the award July 18 during the Traditional Building Conference.

In addition to recognizing his teaching and built work, the honor celebrates Stroik’s “splendid achievements in editorship of Sacred Architecture Journal,” says Labine, founder of Traditional Building, Period Homes and Old House Journal magazines. “Through the Journal he has created a global voice that advances the cause of beauty and transcendence in sacred architecture.”

Muffet McGraw’s résumé doesn’t need much burnishing, with 853 wins, 24 NCAA Tournament bids, seven Final Four appearances and a national title to her credit. Because of all those accomplishments, the longtime Notre Dame women’s basketball coach can add a new entry: member of the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

photo: Matt Cashore ’94

photo: Matt Cashore ’94

She’s one of just six coaches — men’s or women’s — in college basketball history to compile the combination of 800 overall victories, seven Final Four berths and five appearances in the national championship game.

At the April 1 Hall of Fame announcement, McGraw deflected credit to the players, assistant coaches and family members who have been a part of the program.

“I don’t weigh that much,” she said, “but if you look at all the people that have had to prop me up over the years, there’s been a lot of them.”

Laura Carlson wore her motivation on her arm in April as she ran her sixth consecutive Boston Marathon. The 2017 race marked the 50th anniversary of the first woman to run, Kathrine Switzer, who wore bib number 261 and finished despite marathon officials trying to force her off the course.

Carlson, a psychologist and dean of the Notre Dame Graduate School, wrote 261 on her arm in honor of Switzer. Crowds cheered the gesture as Carlson, wearing her own bib number 17144, finished the 26.2-mile course in 3 hours and 55 minutes, an automatic qualifying time for next year’s Boston Marathon.