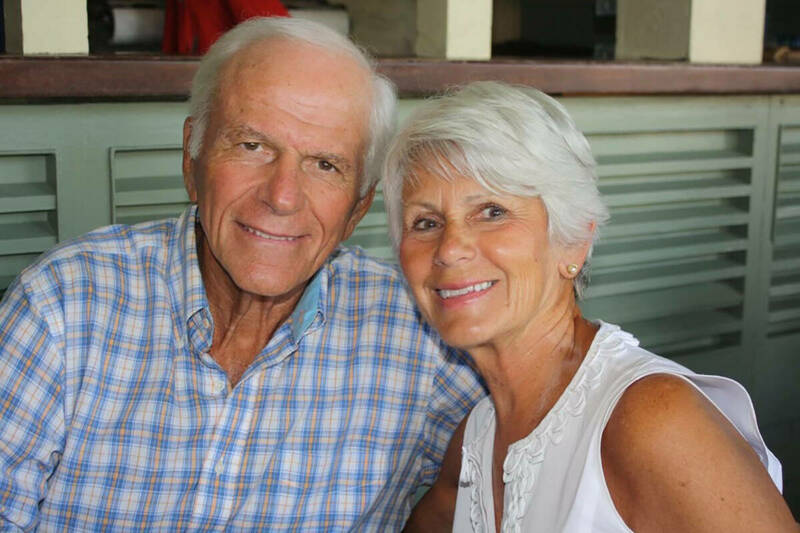

Wherever Ann was, Bill Sexton was happy to be. Photos provided

Wherever Ann was, Bill Sexton was happy to be. Photos provided

Bill Sexton was in a bind. He had to choose between his wife and me. The little plane was ready for takeoff. The propellers were spinning. The three of us stood there on the runway, next to the metal steps and open door. He had little time to think his way out of his predicament. There was anguish on his face.

Maybe I should back up and explain.

When I became editor of Notre Dame Magazine in 1995, I was included among the other department heads in University Relations who made an annual retreat to the University property at Land O’Lakes, deep in the woods where Wisconsin borders Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

We’d go for three days of meetings. We got there by plane — the Notre Dame plane, a little twin-engine prop that seated half a dozen people, including two pilots. So multiple trips were required to get everyone there, even before counting the spouses who were invited to come along.

The days at Land O’Lakes were some of the most meaningful times of my Notre Dame career. Father Hesburgh was always there, and after each day’s meetings we would convene for Mass and a cocktail hour and dinner. In some important ways, I learned there what Notre Dame was all about. Many found time to fish; others canoed or kayaked on the pristine lakes, watched the bald eagles, enjoyed the camaraderie and conversations and wood burning fires. Talks with Father Ted are treasures; we always celebrated his birthday while there. It was right before Memorial Day and some stayed to enjoy the weekend. Some of us took the first plane home.

Ann Sexton changed her mind and decided not to stay. Three others had commitments back in South Bend. There was one seat left. The next flight out was two days away. I didn’t want to stay either, but I was the newcomer, the greenhorn, the rookie. Dr. William P. Sexton was my new boss. How could I tell him “no”? How could I explain that my homelife in those days was not conducive to another 48 hours away? How did it look to turn down two days of fishing, good meals, the northwoods and friendly companionship with him and others?

Bill was near to pleading, turning to me, then Ann, then back to me again. One of you please stay. When the pilot, Bill Corbett, came to see what the holdup was, he learned he had two passengers for one seat. He told Ann to take the seat. And he told me to get on the plane, lie down there in the back, on the floor, with the duffle bags and baggage and whatnot. “Just don’t sit up or tell anyone what we’re doing,” he said, then he waved off Bill Sexton, pulled the door shut and headed to the cockpit, which had no separation from the passengers strapped into their seats for the 90-minute flight down the length of Lake Michigan.

I made the trip flat on my back, in that thrumming, raggedy, vibrating plane.

The pilot’s maverick ways and sound judgment had saved me from letting down Bill Sexton. I spent years working hard not to let Bill down. I owed him. He had taken a chance on me (when others weren’t so sure) when he hired me as editor in 1995. He had stood by me during some skirmishes in my early years when others had wanted me gone. “I just don’t believe in capital punishment for something like that,” he told me later, pithily condensing a discussion that had taken place at the highest levels.

I no longer recall the particular transgression. He and I had several tete-a-tetes before he retired in 2002, with him asking for my defense of magazine stories that had greatly unsettled others. Bill could listen and gently guide, and somehow make me feel better after what began as a stern reprimand. That was a Bill Sexton hallmark: he always made you feel better for having been in his presence. He was, as many said, “a dear, dear man.” He had also been a heavyweight wrestler at Ohio State.

Sexton created a culture of trust and goodwill among those who worked for him, by conferring his trust and abundant good nature. He earned our loyalty and affection with his humility and compassion. His storytelling was full of humor and self-deprecating pokes at his own vulnerabilities. His golf game, his fishing adventures, his parenting exploits.

The evaluations he wrote after annual performance reviews were legendary. He was always prone to hyperbole, but after reading his appraisal, you’d spend the next 12 months trying to live up to the accolades, to become what he somehow saw in you. His leadership came from the example he set. He was on your side. You wanted to do your best for him.

Sexton taught in the business school for 40 years. He was VP for university relations for 20 years, overseeing the alumni association, community relations, various communications departments and development, leading a couple of major fundraising efforts, one exceeding a billion dollars. What meant the most to him, though, was his family — Ann, a daughter and five sons, and all their many children. He loved telling stories of family escapades, and there were many. He loved family times at the lake, at the beach, at ballgames and at home — wherever Ann was.

Bill Sexton died October 17. He was 85.

Each year about this time I write a Thanksgiving tribute to someone to whom I owe a large measure of gratitude. Bill’s recent passing has me thinking back over our days together and my time at Notre Dame and the fact that I am here — and have been here much of this time — because of Bill hiring me as editor, sticking up for me when I was learning on the job, and for showing me what it means to be here, what this place should be.

Kerry Temple is editor of this magazine.