You could say we were drunk on joy.

Or fueled with testosterone. Surfing the crest of the soaring propulsion of fast-release energy. Giddy with silly male exultation.

There were six of us, maybe seven, linked arm-around-shoulders, marching down the road from Stepan Center, past Flanner, behind the North Dining Hall on our way past Farley. It was fall 1973. And we were chanting. Loudly, for all to hear — although I doubt anyone knew what on earth we meant.

“All four years,” we yelled. “All four years. All four years.”

We had not missed a pep rally in our four years as students. As seniors, we had just been to our last. A brotherhood had been forged four years earlier when we followed some upperclassmen into the melee and learned the ropes.

First off, beware of the steel cables — the thigh-high silver cables, strung on concrete-filled iron pipes, to keep students off the grass. All the campus sidewalks were fenced this way; the quads were cordoned off with braided, quarter-inch, galvanized cable. You didn’t want the Meat Squad to sling you over or shove you into the cables.

The Meat Squad was there to protect the band. The band, dressed for fun and frolic, embarked from Washington Hall and marched throughout campus, picking up students along the way — a la pied pipers — navigating the narrow sidewalks while hooligan students got in the way, harassed them, chucked toilet-paper rolls at them. The Meat Squad wore helmets and Meat Squad T-shirts and ran interference, blocked projectiles and dealt with the miscreants, flinging students over the cables, pushing them into bushes. It was all mad fun.

As freshmen, we learned at some point to break from the rowdy parade and high-tail it to Stepan Center to worm our way into the center. The place would already be full of students. We had to push our way in — rivers of newcomer students flowing into a sea of waiting, cheering, chanting students, all mashed together in a sweaty heap of muscular male compression. Then the band came in, from somewhere, horns blaring the Victory March, music echoing off the ceiling, drums reverberating, so much noise your voice was swallowed by the raucous din. Rapture.

Notre Dame was different then. It was an all-boys school, and a less civilized, less sophisticated place. There was no social life. Sports was a way to unbridle emotion, to release pent-up stresses and tension. The pep rally was a therapeutic primal scream, a cathartic explosion of a wild yet harmless riot, a communal expression of unity, loyalty and bravado.

The team would be upfront, almost visible. Coaches and players talked, yelled, exhorted; we cheered them on, wrapped in solidarity and vicarious triumph. The teams were top-gun in those days — full of All-Americans, dazzling QBs and fleet running backs. Even the coaches — Parseghian, Yonto, Kelly, Pagna — were celebrity heroes, capable of whipping the throngs into a frenzy. We yelled and screamed back. We built pyramids, too.

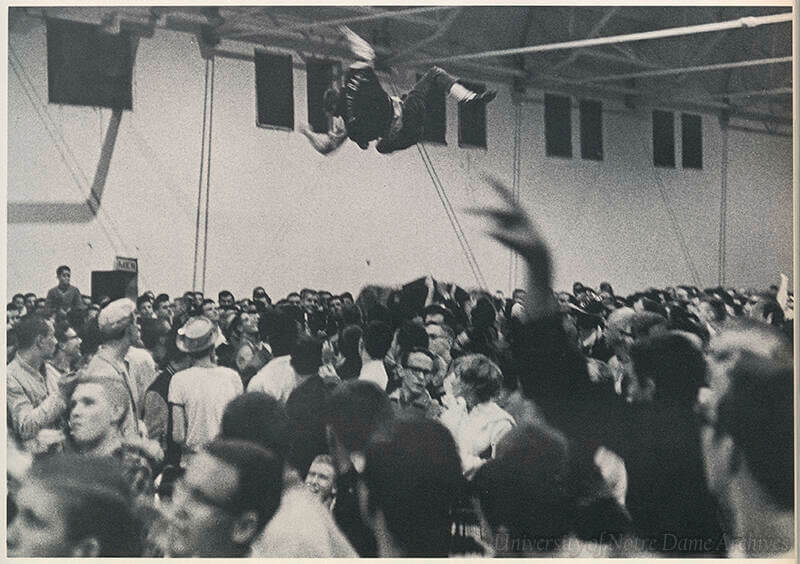

Six or seven guys formed the base, a tight-knit circle, arms around shoulders, heads down — a rugby scrum, but support pillars all upright. Guys then climbed up our backs, forming a second level. Then a third. And finally, some brave guy scaled the human mountain, made it to the top, stood up tall and straight, arms outstretched in triumph and glory. There’d be four or six pyramids at a time within the confines of Stepan, and each would eventually cave and crumble.

We gave no thought to injury or a fall to the concrete floor. There seemed to be no adults around. I remember some cigar smoking. If there had been drinking, it took place before the convening — and none that I ever witnessed. It was a madcap free-for-all of youthful exuberance. A different time for sure.

The Old Fieldhouse preceded Stepan as home to the Friday night pep rallies, held before each home game. As students in the early ’70s, we made it to one rally there — a special occasion, the big game. The players and coaches were seated high on a balcony; the student body packed onto the dirt floor below. It had an old-school, Frank Leahy feel.

The Old Fieldhouse, located where Stonehenge stands today, had been built in 1898 as an all-purpose cavern of brick walls, exposed girders and no floor. Resembling an airplane hangar, it was where the athletes played — from baseball to track to Bengal Bouts. Bleachers could be moved in and wood decking installed when the varsity basketball team needed a place to practice and play its home games. There is a story I’ve heard of Kentucky’s legendary Adolph Rupp complaining of dead spots in the court that interfered with his team’s dribbling. I saw a game there once, visiting my Saint Mary’s College sister and getting to see Austin Carr as a freshman star.

When the Joyce Center opened in 1968, the Old Fieldhouse — dripping roof, leaky plumbing, disintegrating walls — was given to the art department as studio space. Students could store stuff there over summer break. It’s gone now.

So is the pep rally.

I cannot say I mind.

The pep rally had become a shell of its former self, a victim of a changing culture. Its time had passed. Attempts to keep the tradition alive were overly engineered, excessively choreographed; they lost their spontaneity. They became shows for visiting fans and families, on campus to take in the whole Notre Dame football experience. In many ways, the place had grown up, the students, too. As cultures adapt and evolve, some rituals lose their power, then forfeit their relevance.

It’s OK, though, to be nostalgic for what once was, the way things used to be — especially when you’re aware of the primitive forces that spawned them, how juvenile the behaviors, how witless it all seems now, looking back. I admit to all that. But those pep rallies sure were fun.

Kerry Temple, editor of this magazine, was in attendance at the Sugar Bowl his senior year when the Irish beat Alabama for the national championship.