“Bicycling may be the riskiest thing we do these days,” one of my friends said recently.

Is it so? I consider other daily risks. Ascending my staircase, my laptop rests on the arm transporting my mug of tea; a misstep would send the beverage swirling into the computer’s crevices. The plastic grocery bag I select to hold my lunch has a tear just wide enough to permit a utensil to slip through it. I place my fork on the opposite side, trusting it will not migrate during the morning. Nonetheless, amid my daily temptings of fate, I acknowledge a certain thrill while riding my bike in the city.

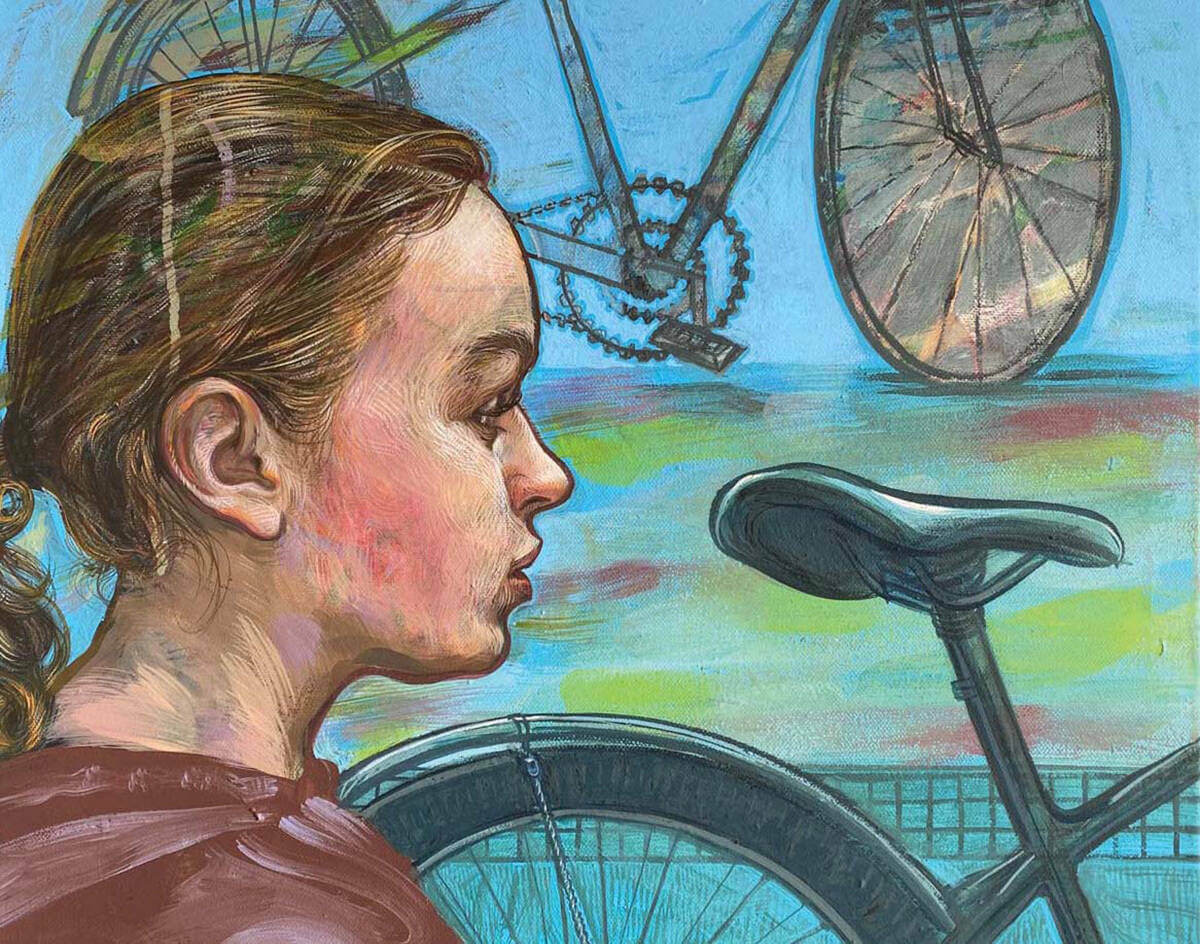

I am neither a cyclist nor a biker. A cyclist is concerned with aerodynamics. Biking signifies gear that is black, sleek and emits exhaust. I am someone who rides a bicycle. I don’t deserve a label. Indeed, I wouldn’t want any label that would commit me to regular tune-ups or investing in cycling gear. If I had a moniker, I suppose it would be something like “pedaler,” not unlike qualifying oneself as a “jogger” versus a “runner.”

A few years spent living in Chicago fostered my confidence in city bicycling. A duo of bike-riding sisters, my friends Claire and Jane, inspired me. One Easter when I was housemates with Claire, Jane rode to our house and unsheathed a pristine coconut cake from her rear basket. I was acquainted with Jane’s culinary skills and her bicycling prowess, but the combination of the two was something else entirely. Had she uncovered an incubator of hatching chicks that sunny Easter afternoon, I don’t think I would have been more awed.

“Melancholy is incompatible with bicycling,” a quote attributed to forensic scientist-lawyer-cyclist James E. Starrs, comes to mind as I breeze through city streets on my bike. I think of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, a technique to heal from trauma that involves saccades — quick movements of the eyes between targets. A similar scanning is required while riding just to maintain vigilance in a changing environment. On my right I am threatened by the inattention of a woman who has parked and is investigating her purse contents while swinging open her car door. On my left I am encroached by a driver fiddling with his air-temperature controls. Maybe the necessity of looking outside of ourselves, again and again, ameliorates our inner pains and wounds: those salvific saccades.

Freedom rewards the risk. In childhood I wondered why adults, given their autonomy, live in such routine ways. My childhood dream home contained multiple means of transport. A fire pole connected the top and bottom floors. A chocolate lazy river flowed from the den to the kitchen. I could float to dinner in a doughnut innertube. So many adventurous ways to get from here to there! Maybe not all our visions are realizable, but maybe more are than we know.

Arriving somewhere by bike feels like I am swindling the system. Parking a bike is easier than parking a car. No need to circle the block or parallel park; I simply chain the frame and wheel to a signpost. Parking comes at a premium in the city. “I got a good spot,” boasts someone who has parked a block away from the venue. I got a good spot, I think. I parked on the sidewalk.

When I consider what can be accomplished on two wheels, I do not think of the Tour de France; instead, I picture Jane’s coconut cake. A cake is unnecessary, pure pleasure. It transcends routine. During preparation, ingredients thwart gravity. Dumped flour puffs heavenward. Giddy gas bubbles rise in baking batter. Once cooled and iced, coconut curlicues cling tenuously to the cake’s sides. A curtain flutters above the sink, as if jittery from the kitchen’s sugar content. Not only is the final product of the cake fun, so in this case was its process of arriving.

Is city bicycling the riskiest thing I do these days? I consider my friend’s statement as though shifting my weight while paused at an intersection — one foot on the ground, the other on the pedal, acknowledging relative risks but also the precautions I take. In a moment the light will turn green, and I’ll lift off. I won’t be stalled long enough to arrive at an answer, but in this snatch of stillness I fiddle with one piece of evidence: my headwear. Although I like the appearance of someone bicycling with her hair flailing wildly, common sense imprisons my hair in my helmet. It travels proximal to the pleasure of the wind but not fully immersed in it.

Perhaps as a reward for good behavior, when I arrive at my destination and finally unclasp and remove the helmet, I allow my hair to indulge in a belated taste of freedom. My crowning waves crest and trough like icing before a spatula’s taming. I’ll rake through them soon, but for the moment I simply shake my head in the breeze, letting the unruliness go unchecked. It’s as if it had been trying to get out the whole time.

Erin Buckley lives in Richmond, Virginia, where she works as an occupational therapist.