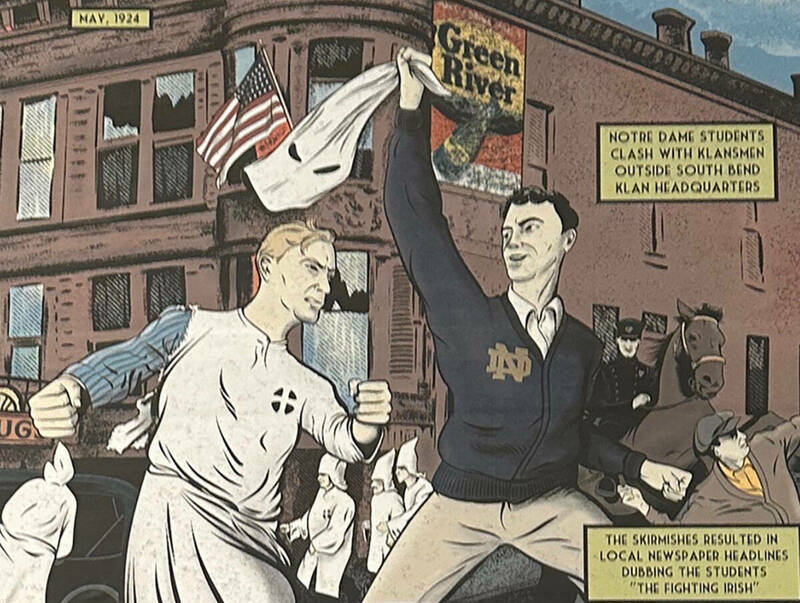

An illustration depicting Notre Dame students disrupting a South Bend demonstration by the Ku Klux Klan. Photography by Margaret Fosmoe ’85 of images on display at the Indiana Historical Society.

An illustration depicting Notre Dame students disrupting a South Bend demonstration by the Ku Klux Klan. Photography by Margaret Fosmoe ’85 of images on display at the Indiana Historical Society.

The stories and black-and-white photos from that day a century ago when Notre Dame students brawled on the streets of South Bend with members of the Ku Klux Klan may seem shrouded in the distant past.

But in other ways, the scenes feel like they could be ripped from the news headlines and social media posts of today.

Tirades against immigrants, racial minorities and people of other faiths. Racism and xenophobia providing talking points in the public sphere. Individuals who demonize the “other” to court votes and get elected to high public offices.

Those targeted as outsiders may have changed, but the rest sounds oddly familiar.

It was a century ago this month — on May 17, 1924 — that University of Notre Dame students flooded into downtown South Bend to confront members of the Ku Klux Klan who were arriving for a community march and picnic.

At the time, Catholics — and Catholic immigrants, in particular — were considered outsiders by much of American Protestant society. Catholics were suspect, perhaps more loyal to the pope than patriotic to the United States, their detractors suggested.

The 1924 confrontation is examined in an exhibit, “RESIST!: Notre Dame Students Stand Up to the KKK,” which continues through August 2, 2025 at the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis.

The exhibit depicts the growth of the Klan in that decade, the leadup to the South Bend riot, followed by the sudden and dramatic downfall of the group after its Indiana leader was convicted of abduction, rape and murder.

A related exhibit, hosted by The History Museum, will be on display May 17-October 13 at the St. Joseph County Public Library in downtown South Bend.

The Notre Dame students’ victory over the “Invisible Empire” was detailed in a 2004 book, Notre Dame vs. the Klan, by Todd Tucker ’90. The South Bend brawl and the larger story of what led to the fall of the Klan in Indiana and nationally also are chronicled in Timothy Egan’s 2023 book, A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped them.

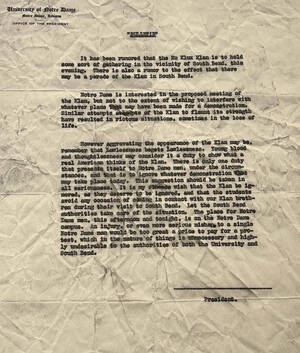

On that Saturday morning a century ago, Notre Dame President Father Matthew J. Walsh, CSC, issued a campus bulletin urging students to ignore the Klan gathering in town and stay on campus.

The student body disregarded the missive and headed downtown.

Notre Dame men misdirected arriving Klan members, then followed them down alleys and confiscated their white robes. Klan members insisted they would march, even though the city police chief had denied a permit for a parade. Fisticuffs broke out on downtown sidewalks.

The students unmasked Klan members and chased them back to the group’s local headquarters. The tense situation lasted for three days, culminating with the students lobbing potatoes and other missiles at a “fiery cross” — a wooden cross lit with red light bulbs — hanging from the group’s third-floor office window.

The confrontation ended when Walsh arrived and spoke to the students from the lawn of the county courthouse. He quieted them and urged them to return to campus.

The Indianapolis exhibit includes a photograph of Notre Dame student William Foohey wearing a Klan robe he reportedly seized from a visiting Klansman on that day. (Foohey went on to earn three Notre Dame degrees and had a long career as a Du Pont research chemist.) There’s also a photo of the Klan headquarters in South Bend with its smashed window and cross.

The original Ku Klux Klan rose in the South in the aftermath of the Civil War, its members donning white sheets to hide their identities as they terrorized African Americans with lynchings, arsons and bloodshed. Facing backlash, that Klan was all but gone by 1872.

The Klan’s second incarnation was born in 1915 in Georgia, inspired in large part by the blockbuster D.W. Griffith film The Birth of a Nation, with its gross racial stereotypes and depiction of cross burnings, which played to packed movie houses across the nation. (Notre Dame students got to see it during a Washington Hall screening in December 1915.)

The film was “was the most effective and long-lasting source of racial propaganda in American history,” Egan writes.

The reborn Klan flourished in 1920s Indiana, with members focusing their disdain at Jews, African Americans and Catholics. At the time, Jews composed just 1 percent of the state’s population; Blacks, 3 percent; and Catholics, 10 percent. In comparison, more than 95 percent of Indiana’s population was native born and 97 percent of residents were white.

The state was a welcoming place for those who sought to demonize the “other.” Indiana in 1905 had passed the world’s first eugenic sterilization law, targeting “idiots, imbeciles, and confirmed criminals,” in the words of that law, to assure such individuals would not reproduce.

The Indiana Klan was led by D.C. Stephenson, a charismatic figure with a shadowy background who was skilled at packaging prejudice into eye-catching rallies and parades. Wives belonged to the Klan’s women’s auxiliary, and children marched in parades of the Ku Klux Kiddies.

In 1923, Stephenson had a plan to buy Valparaiso University — at the time a Methodist institution — and turn it into a Klan-affiliated school. That never came to fruition.

Stephenson’s downfall came suddenly and dramatically, as recounted in the Tucker and Egan books.

There are heroes in this story:

George Dale, a weekly newspaper editor in Muncie, Indiana, who reported about and crusaded against the Klan, was attacked, pistol whipped and spent time in prison at one point for alleged libel.

Arthur Gilliom, a South Bend attorney who fought against the Klan’s parades in the city, was later elected Indiana attorney general and filed suit to revoke the Klan’s state charter.

Attorney Patrick H. O’Donnell, who led the American Unity League, a Chicago-based organization, published the names and hometowns of midwestern Klan members in Tolerance, the league’s weekly newspaper.

And most significantly, Madge Oberholtzer, a young Indianapolis woman whose brutal rape, agonizing death and deathbed recounting of Stephenson’s actions brought about his criminal conviction and downfall.

Months after the melee in South Bend, Notre Dame rose to national prominence through the accomplishments of its football team — particularly the legendary backfield dubbed the Four Horsemen — coached by Knute Rockne. (Rockne, a Norwegian immigrant, converted to Catholicism the following year.) Rockne’s 1924 team went 10-0 and beat Stanford in the Rose Bowl, claiming the University’s first national championship.

The clash on the streets of South Bend a century ago helped cement the use of the term “Fighting Irish” in reference to Notre Dame. The term was used in newspapers to refer to the football team as early as 1914 and its use may date to as early as 1909.) It picked up steam after the Klan riot and the University’s rise on the gridiron.

In 1927, Father Walsh decided the “Fighting Irish” was preferable to more derogatory nicknames and officially approved its use. “The university authorities are in no way averse to the name ‘Fighting Irish’ as applied to our athletic teams,” the priest said. “I sincerely hope that we may always be worthy of the ideal embodied in the term ‘Fighting Irish.’”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.