In the dead of January 1916, the ambitious young priest in charge of Notre Dame’s library wrote to an alumnus named C. Stockdale Mitchell, class of 1894. He thanked the prosperous Texan for his donation to the University’s growing collection of rare books, then asked a favor: He wanted Mitchell to call on a distant neighbor and practice “a little diplomacy” on their alma mater’s behalf.

“There is a person who has recently settled in Matagorda Bay by the name of Senor S.C. Braganza de la Coralla,” Father Paul Foik, CSC, elaborated. “Do not get frightened at the name. Be rather afraid of the man should you meet him. He has led a most romantic life, and in his wanderings he has picked up a number of rare historical treasures that I would like to get possession of for the University of Notre Dame.”

It seems this Braganza had introduced himself to Foik as a Spanish count and former soldier of fortune who as a much younger man had seen action in Peru. From there, Braganza claimed, he had spirited books away “by means of the robber rights which War gives.”

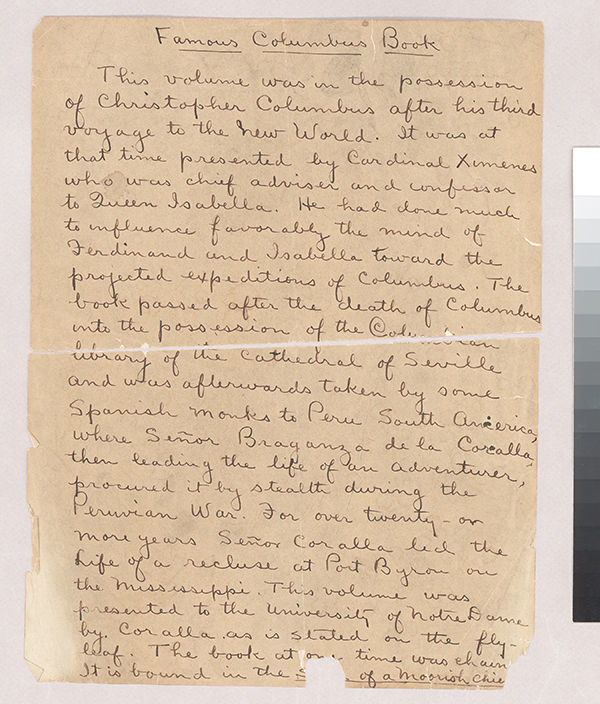

Braganza’s main enticement was a book published in 1504 that he said was once owned by Christopher Columbus, brought to the New World by Spanish monks whose monastery now lay in ruins.

When he wrote Mitchell, Foik had this precious catch in hand. He had retrieved it one week earlier from Braganza’s former residence on the Illinois banks of the Mississippi River.

Now the priest had his eye on other allurements in Braganza’s collection. Not the “chair belonging to Marie Antoinette in which she reclined a short time before she went to the guillotine,” he told Mitchell, but three historic Bibles and a copy of the “suppressed Book of Mormon” — and who knew what else? — “which along with what we already have shall make our collection famous.”

Mitchell, Foik warned, would have to be sly if he accepted the mission, and not just because of whatever skill with pistol or sword the old mercenary might still possess. Months earlier, Braganza, 73, had arranged his own marriage in Chicago to a teenage girl, the daughter of a Lithuanian janitor, whom Foik had sized up as a gold digger. The librarian felt correspondence with Braganza would fall into the hands of this “young witch, who, I am afraid, is as much of an adventuress as he is an adventurer, or was in his earlier days.”

Meanwhile, Foik had alerted the newspapers about his Columbus book, just as he would later that year when he secured a cylindrical cuneiform tablet from ancient Babylon and five books from the library of Dr. Edwin Heath, the “noted South American explorer.” Interest in each item was high, but nothing matched the attention paid Columbus. News of Notre Dame’s connection to the Discoverer of the Americas electrified the national wires.

No doubt reporters’ ears perked to one detail that Foik somehow forgot to mention in his sensational plea for Mitchell’s help. His prize find was bound in human skin.

The skin of a “Moorish chieftain,” to be precise.

The story Señor Braganza told

The book arrived at Notre Dame with that story. The story became legend, repeated for decades by librarians, campus tour guides, student publications and local journalists. Whatever anyone once knew with certainty about “the human skin book” — how it was made, where it had traveled and how it survived its 412-year journey from the printer’s press in Strasbourg in modern-day France to the librarian’s desk under the Golden Dome — was soon buried beneath the sediments of storytelling and time.

Who wrote the book? What was it about? Bah. Minor details that non-librarians often left out or rendered incorrectly. Who wanted to hear about the collected works of the 15th century Florentine philosopher and humanist Giovanni Pico della Mirandola when “Christopher Columbus” cast such a satisfying historical shadow?

To examine it, fill out a call slip and wait in the Rare Books & Special Collections reading room for a student intern to consult with a curator. Assuming no objection, that curator will retrieve the book and its gray cloth box from the top shelf in a back corner of a locked steel cage the curators call the “upper vault,” where its neighbors include a copy of the gospels in “Anglo-Saxon” and something called the “Curious Bible.”

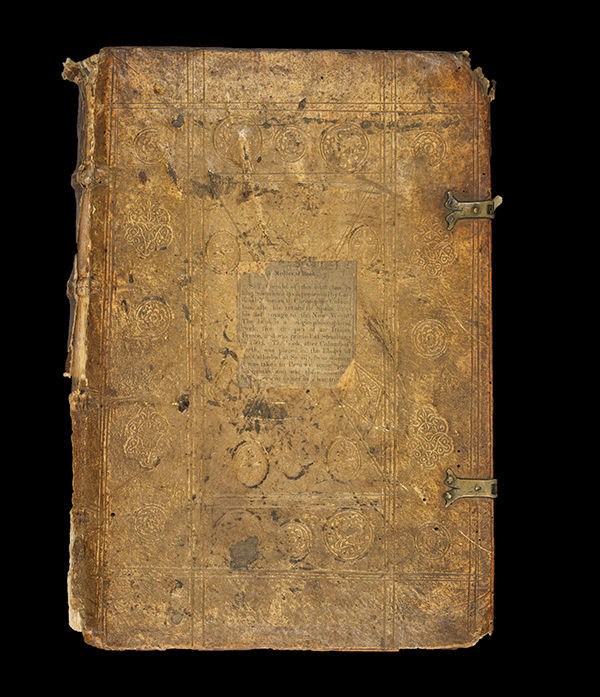

At first glance, the book as an artifact may seem unremarkable for its age. It’s roughly 8½ by 11¾ inches, and its 228 leaves stack 2 inches high between wooden boards covered in an alum-tawed hide of light, mottled brown. Four raised bands across the spine, the patterns of ungilded stamping into the hide on the cover and two sets of brass clasps all indicate that the book was probably printed and bound during the same time period, an era when those tasks fell to different craftsmen.

A hole in the book’s lower board indicates a missing hasp, suggesting it was “most likely” chained to a lectern or bookshelf for consultation before it came to Notre Dame, says rare books curator David Gura. And the bottom half of the spine has fallen off. Chewed by an animal, says the library’s lead conservator, Liz Dube. Rats, suggests conservation fellow Sue Donovan.

Now take a closer look. Adhered to the book’s front cover is a square of yellowed newspaper bearing a tiny headline: “A Medieval Book.”

“A S.T. Coroilo of this city has in his possession a book presented by Cardinal Ximenes to Christopher Columbus after his return to Spain from the last voyage to the New World,” the clipping begins.

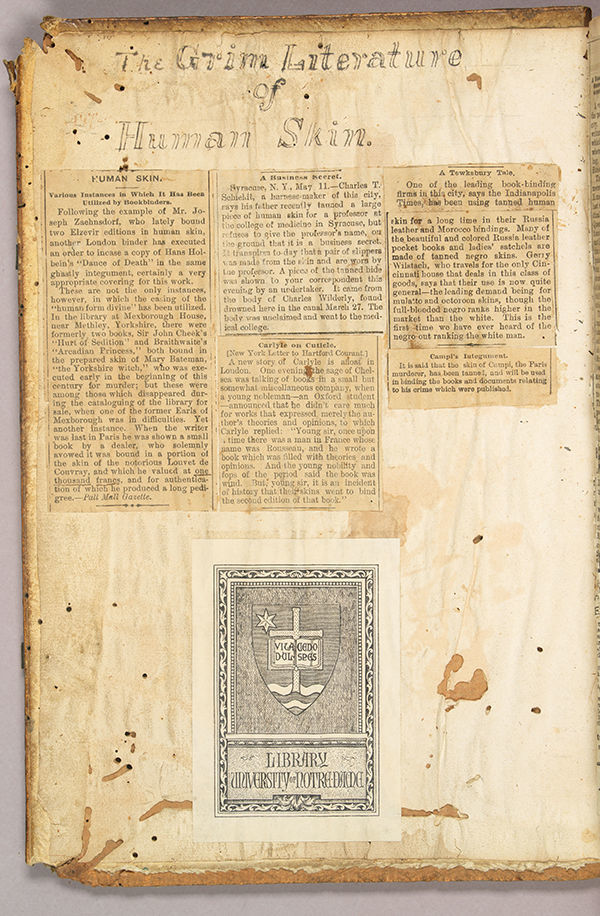

Open the cover to find newspaper clippings attached to the wormeaten pastedown endpaper recounting five other instances of what librarians call “anthropodermic bibliopegy,” the uncommon practice of human-skin bookbinding, all beneath a handwritten heading in creepy Victorian lettering that reads “The Grim Literature of Human Skin.” On the flyleaf opposite, two longer articles marvel at the private collections of Sebastian Carroll Braganza de la Coralla and relay his account of the book.

To expand Braganza’s story: “Cardinal Ximenes,” or Francisco Jimenez de Cisneros — friend to Columbus, adviser to Ferdinand and Isabella and ruthless adversary to Spain’s remaining Muslims at the turn of the 16th century — was the powerful Archbishop of Toledo when the explorer returned in November 1504 from his fourth and final crossing to Spain’s new lands across the Atlantic.

Sometime before Columbus’ death in May 1506, the archbishop is supposed to have given his ill friend this copy of the writings of the late Pico della Mirandola, whose reputation as an intellectual wunderkind had spread across Europe while Columbus was away. Jimenez ordered the book bound in the skin of some nasty Islamic foe of Christianity and stamped a blank page with his ecclesiastical seal. After Columbus’ death, the book entered the collections of the library in Seville’s cathedral, where the old mariner was buried. At some point during the next 350 years, a Spanish monk packed it up and sailed to Peru, where Braganza nicked it as a war trophy.

Librarians call the story of a rare book’s ownership its provenance, and as ownership stories go, this one’s a corker: A severe churchman, a pivotal moment in Western civilization, a towering historical figure, a plausible if fantastical narrative of the book’s subsequent passage through time.

There is this one problem with Braganza’s story, notes George Rugg, the rare books curator charged last year with investigating it: No part of it has ever been verified. The archbishop’s seal, “the one thing other than clippings” that would definitively link the book to Jimenez, Columbus and Spain? Nowhere to be found. Apart from Braganza’s capacity to sell his tale so often that its published retellings generated their own veneer of authority, there’s no proof he was anything more than a master of historical fiction.

There was still that gruesome claim about the binding material. In that sense, the truth about the book could only be adjudged by its cover.

The science trail

Let’s give Father Foik a pass. After all, it’s his name on Notre Dame’s highest annual award for librarians, and for good reason. A historian by training, a librarian by appointment only, Foik, Class of 1907 and 36 years old in the winter of 1915-16, had larger matters on his mind than the coy allurements of a Spanish nobleman from Rapids City, Illinois. So far, this story has mentioned four Hesburgh Library employees by name; back then, Foik was the entire staff. And, he was hard at work on plans to move the library out of its cramped digs in the Main Building and into a standalone building yet in blueprints that would become today’s Bond Hall.

The Columbus story persisted without scrutiny past Foik’s departure in 1924. Paul Byrne, his successor as library director, put the book “made of human skin” on display several times in the 1920s and 1930s, and articles about it took several comical turns. After one exhibition in 1926, the Scholastic mistook it for a bible; another Scholastic scribe 11 years later thought it was something called the Journal of the World and was published in 1634, not in 1504. In 1966, a Sunday features writer for the South Bend Tribune informed readers that the book was owned not by Columbus but by his son.

When the library celebrated the quincentennial of Columbus’ landing on Hispaniola in 1992 with an exhibit of early printed books related to the “Columbian Encounter,” the invitation mentioned “a book said to have been owned by Columbus himself,” but nothing about human skin. Rumors could still be heard in graduate history seminars and library concourse chatter, but the librarians themselves had grown skeptical.

By this time Braganza was no more than a name on a few scraps of paper and his tale had worn as thin as the binding itself. Still, it was the only story the library had.

Liz Dube, the conservator, recalls showing the book in 1999 to a colleague who had done leather research and was interested in human skin bindings. They magnified the cover and squinted to find a follicle pattern, the best visual clue to the mammal from which a hide has come. They couldn’t rule out a human source. Library officials considered having the book tested, but without promising leads the idea fell behind higher priorities.

That might have ended interest in Notre Dame’s “1504 Pico,” one of 10 extant copies in U.S. libraries according to Julie Tanaka, under whose curatorial purview the book falls. Rare Books continued to show it to the curious upon request but wasn’t advertising its existence. Another few years and the book, like its donor, might have been forgotten.

Then, in the summer of 2014, The New York Times reported that Harvard University had tested three suspected anthropodermic bookbindings among its collections using protein mass spectrometry. Two covers proved to be sheepskin, but a third book, a 19th century French monograph on the soul, was confirmed as covered in human flesh. The announcement rippled across the blogosphere and at Notre Dame kickstarted the testing idea anew, seeking answers in DNA or maybe proteins. Now the question was how to proceed without risking undue damage to an old book already stressed from overuse.

Dube pulled the Pico once again and began asking for information on mass spectrometry. She started with anthropologist Sue Sheridan, a bone expert whose lab in the Reyniers Life Building is upstairs from hers. Dube knocked on Sheridan’s door one day that autumn and said, “Wanna see something cool?”

Sheridan suggested Dube start by talking to Jada Benn Torres ’99, a genetic anthropologist who uses DNA to answer questions such as how the Caribbean was inhabited. But the book’s age took it outside Benn Torres’ immediate expertise, so she pointed Dube to Graciela Cabana, a molecular anthropologist at the University of Tennessee-Knoxville whose “ancient” DNA lab specializes in the extraction and amplification of DNA from long-dead sources.

That’s where things got complicated. Extracting DNA from a 512-year-old bookbinding, Cabana says, means distinguishing it from the DNA in the animal byproducts used to treat and glue the skin, as well as from the genetic jumble left behind by everyone who’s ever handled it.

But where DNA and follicle patterns are fragile even under ideal conditions, proteins like the hemoglobin in our blood and the collagen in our skin endure. Protein analysis like the kind Harvard had performed presented the best path forward. For Dube, it led through Cabana’s contacts to Donald Siegel, principal scientist at the Office of Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) in New York City, who agreed to take the cold case.

The New York OCME performs all forensic testing for the city’s police and by law investigates every death in the city that occurs “in an unusual or suspicious manner.” Whenever an examiner cannot identify a sample of soft tissue or bone fragment or simply wants a second opinion, they turn to Siegel’s lab for answers. Funded by a grant from the National Institute of Justice, Siegel and his colleagues are developing time-of-flight mass spectrometry techniques to improve the reliability of species identification as a forensic tool. “We eventually want to make this a test that medical examiners around the U.S. and the world will use,” he says. He thought the Pico binding would be a “slam-dunk” demonstration of its refinement.

What he encountered instead was “the most ambiguous of all the samples we have tested.”

Siegel describes mass spectrometry as simply “a very sensitive scale” that can measure minute differences in mass. Siegel’s technique first fragments a collagen sample into chains of amino acids in the collagen called peptides, then weighs the fragments, seeking tiny differences that may rule out certain species. Then, after a second fragmentation, Siegel uses software to inventory the sequences of amino acids in each chain and compare them with existing peptide data taken from well-established species. Could Siegel find an unassailable species match for the collagens in the Pico binding?

Dube sent Siegel a small circular punch from beneath the pastedown endpaper on the book’s back cover and a matching punch from a volume printed and bound at Basel, Switzerland, in 1569, as a control. Siegel sliced each sample piece into three layers to further minimize the threat of contamination.

By June last year, he offered Dube preliminary results: the Pico and control samples were consistent with multiple species, including primate. “Seems inconceivable that both would be human,” Dube commented in an email, “but not impossible.”

As Siegel dug deeper, reaching out to colleagues at New York University who use a different spectrometer and approach, the more familiar historical work of provenance research at Hesburgh Library was underway.

The strange story of Señor Braganza

If the Pico turns out to be bound in human skin, “you could knock me over with a feather,” George Rugg had said last April when he began looking into the life of its donor.

From the outset, Rugg and fellow curator David Gura shared the hypothesis that since the binding showed all the signs of being contemporary with the printing, the material would prove to be pigskin, commonly used by German bookbinders at that time.

On the other hand, Rugg conceded, “just because a story is wacky doesn’t mean there’s no grain of truth in it.”

There is no doubt Sebastian Braganza left Notre Dame an authentic early copy of the collected works of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola. He’d gotten it somewhere. If he was making up the Columbus story, why? There is no evidence that Father Foik had paid for the book, or that Braganza asked for anything more than “that the donor and his deceased mother be remembered in the suffrages and orations of the community.”

While Rugg could find neither Archbishop Jimenez’s seal nor any attempt at a forgery, he did spot among the marginalia that appears throughout the book, in scholarly handwriting Gura confirms as common in the 16th century, one clue. Sum Christophori Binderi. “I am Christoph Binder’s.”

That statement of belonging posed the strongest challenge yet to the Columbus narrative. Historians of religion in Reformation Germany might recognize two figures named Christoph Binder. The elder was a 16th century Lutheran abbot and theologian in Adelberg, Germany, a town maybe 200 miles east of Strasbourg. His grandson, who died in 1616, was also a Lutheran theologian, less famous but more prolific as a writer, Rugg said.

The book cannot have been in Germany and in Spain or Peru at the same time. Nearly as preposterous is the idea that it had zigzagged across Europe — from the Free Imperial City of Strasbourg, home of Gutenberg and his printing press, to Archbishop Jimenez, Spain’s future Grand Inquisitor, to Columbus and the Cathedral of Seville, and back again to a family of Lutheran theologians in Germany — all before journeying across the Atlantic.

So, who owned this book?

Its author provides interesting grounds for speculation. Giovanni Pico was a pretty fascinating guy, a landed Italian nobleman who drank and recited poetry with Lorenzo de’ Medici, Lord of Florence, and presumed upon Lorenzo’s protection when he made off with the wife of one of his cousins. Pico lived fast and died young — in 1494 at age 31.

He was also a brash and original thinker, says Professor Denis Robichaud of Notre Dame’s Program of Liberal Studies. Pico was a pioneering scholar of the Bible and of the intellectual heavyweights of Greece and Rome who believed he was hot on the trail of “philosophical concord,” an articulation of the common seeds of truth and human thought.

At 23, Pico had issued Europe’s leading scholars an open invitation to his defense of his 900 theses on theology and philosophy. The Church found fault with 13 of them, condemned the lot and placed Pico under house arrest. Would the writings of such a mind have likelier appealed to an orthodox Catholic archbishop like Jimenez, or to a son of the Reformation like the Binders? Pico embroiled himself in other controversies that may have appealed to the reforming spirit of his times, but he never left the Church. Bottom line: Who knows?

Meanwhile, Rugg dug up what he could on Braganza.

Sebastian Carroll Braganza de la Coralla, according to his record in the U.S. Census of 1910, was born abroad or possibly at sea in 1842 to a woman from Maryland and a man from South America. Living alone on his own income in a rental house near Rapids City, Illinois, Braganza acknowledged a divorce on his census form. One note to Foik alluded to living children whom he wished to exclude from his legacy.

He was no stranger to American newspapers, which seemed to regard him as an amateur authority on seismic and weather predictions. In April 1908, the Dallas Morning News reported that an earthquake Braganza had warned would level Chicago had “failed to materialize.” Five years later, papers across the Midwest and Great Plains reported on a letter predicting catastrophic five-day storms. It, too, came from the “meteorological expert . . . widely known because of his controversy with the United States weather bureau.” This apocalypse fizzled, too.

The old yarnspinner had one more adventure in 1915 when, between communications with Father Foik, he responded to an advertisement in the Chicago newspapers seeking a “good wealthy husband of high education” for a 15- or 16-year-old girl named Ludvika Ginetis.

The Ginetis family, so the story goes — pieced together from further research in newspapers and the manuscript of an aspiring Texas writer who considered turning the tale into a novel some 20 years later — accepted the proposal of “the Count,” and the odd couple married. Ludvika’s parents, younger brother and sisters accompanied the newlyweds to an estate Braganza had purchased in Matagorda, Texas, purportedly with proceeds from his sale of another property in Brazil. Ludvika, as smart as she was beautiful, would help the count record his observations of the heavens and provide him, he hoped, with a new heir.

These plans had soured by the time Foik wrote Stockdale Mitchell in January 1916.

The estate turned out to be a modest, abandoned house on scrubby land. The Braganzas and Ginetises spent the winter quarreling in a home the count rented in town. Money was running out. Suspicions and resentments flared. Then, in the first week of March, Ludvika’s father appears to have lost his mind. Neighbors who responded to gunshots in the family’s front yard found Mr. and Mrs. Ginetis dead in an apparent murder-suicide.

In another letter to Mitchell, dated two weeks after the double shooting and on file in the University Archives, Foik indicates he’d had Notre Dame’s president, Father John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, write Braganza a condolence letter. Still wary of Ludvika, still interested in the count’s books, Foik again encouraged Mitchell to make contact. “I have never seen the old fellow nor what he has still to offer,” he wrote, “but I judge from what I have already seen that he is worth cultivating.”

What is known today at Notre Dame about Sebastian Braganza ends there.

Emmie Parris Johnson, the Houston writer whose account of the saga is at least as plausible as the newspapers’, says the count later abandoned his bride when informed she’d had an extramarital affair. Braganza took the next train back to Illinois where he’d left money at a soldiers’ retirement home near the banks of the Mississippi, set to begin the last chapter of the Mark Twain novel from which he came.

So we tanned his hide when he died, Clyde

As 2015 wore on, certainty at New York’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner proved elusive. While the Pico and the control were “scientifically indistinguishable” from one another, pig peptides were the most common in both bindings, but goat, sheep, primate and even camel peptides were turning up. Siegel spent hours at home reading about 16th century practices and speculated that bookbinders may have processed various hides in their cauldrons, unwittingly cross-contaminating their product with the biological residues floating in their caustic soups.

By October, another approach had emerged. Dube asked Siegel to forward the Pico and control samples to Daniel Kirby, the independent conservation scientist who had used peptide mass fingerprinting to confirm the human skin binding at Harvard. Kirby is an associate in The Anthropodermic Book Project. As of last December, the group had tested 30 of the 48 suspected human skin books at libraries and museums around the world, confirming the dermis of a homo sapiens as the wrapper on 16 of them.

“The historical reasons behind [these bindings] vary,” the project’s website, anthropodermicbooks.org, explains. A few Victorian-era doctors used them “as an act of veneration” for the study of medicine, “while at the same time they were used to punish convicted murderers.” Each confirmed case adds detail and nuance to these explanations.

Peptide mass fingerprinting, or PMF, uses that first round of mass spectrometry in its analysis. Like Siegel, Kirby targets collagen, the chief building block of mammalian skin, bones and connective tissues that Kirby describes as “unique in its ability to survive a long time under harsh conditions.” Collagen is “99 percent” identical from one mammal to another, he says. The trick is to isolate those small evolutionary differences that distinguish the collagen of one species from another, whenever even a single amino acid replaces another in a peptide. You can see that minuscule shift if you measure the molecular weight of certain ionized peptides across several species and look for marker ions with unique masses — a peptide’s mass “fingerprint.”

On page 3 of the report Kirby sent Notre Dame in December, one fingerprint stands out. Look on the left of the chart, he says. “The unique one in this case is the 1121,” representing a weight in atomic mass units that is 26 units heavier than the same peptide in all mammals but one.

It is labeled “Pig X.” It wouldn’t appear unless the binding came from a pig, Kirby says.

“PMF results from both volumes are consistent with a porcine source, based on characteristic PMF marker ions,” he concludes in his report. “Other sources such as sheep, cattle, goat and deer, as well as human, are clearly excluded.”

Siegel, who has corresponded with Kirby, has doubts. The likelihood it’s pig is probably higher than 50 percent, he says, but his team also found other “unique” species masses in the spectra. “Why are we getting all these other things? They concern me. Maybe because this is a forensics lab, and I certainly wouldn’t want to send somebody to jail on this evidence.”

On the other hand, the sample in question isn’t a piece of organic soft tissue dug up by someone’s dog in Central Park. (“Not uncommon,” Siegel says.) It’s a bookbinding. From the standpoint of the best available conservation science, Kirby is “quite confident” that the answer to a century-old Notre Dame mystery is pigskin.

The claim to being bound in the flesh of a Moorish chieftain thus refuted, the last remaining thread of evidence linking the book to Columbus and the Spanish Inquisition vanishes with it.

You have to hand it to Sebastian Braganza, who was born the year P.T. Barnum introduced his first lucrative hoax. The count finally put one over on people even if, unlike Barnum, he didn’t make money off the deal. Notre Dame’s “human skin book” lasted one month shy of one hundred years, taking its place in a rich history of frontier hoaxes.

Disappointed? Don’t be, the librarians say. Father Foik, for his overwork and youthful excesses, wanted nothing less than to create a credible university library run by a well-trained professional staff. For the cost of a few scientific tests, the Pico project has left its many participants richer for the experience. Research in provenance is an essential service librarians provide their scholarly community. “In this case,” says Rare Books & Special Collections head Natasha Lyandres, “it required working with scientists to get to the truth of the matter.”

Freed from its associations with Columbus, Notre Dame’s copy of the 1504 Strasbourg Pico and the cryptic annotations inside it may hold answers to yet-unasked questions about the influence of the philosopher-prince’s thought on the development of Lutheran theology. Debates over his work are alive and well, Denis Robichaud says, as scholars chew over translations, the authority of early editions and Pico’s diverse contributions — as a Latin stylist, as a mediator between medieval scholasticism and modernity, and as a commentator on everything from Scripture to astrology to human dignity.

As for Braganza: When it comes to it, we know nothing about him. Was he crazy? A failed con man? Was the information he furnished to the U.S. Census Bureau genuine?

Even his name seems counterfeit.

“Braganza” is a royal name, but of Portugal, not of Spain. Coincidentally, perhaps, the “Braganza diamond” is one of the great legends of the 19th century. The Portuguese crown jewel may have been one of the largest rough diamonds ever discovered, or it may have been a topaz. It reportedly disappeared after the death of King João VI in 1826 — if it ever existed.

Then again, maybe Braganza was who he said he was — even if what he said about the best-known of Notre Dame’s 3.3-million-plus volumes wasn’t true. In the end, the most real thing about this storybook adventurer seems to be the collected works of Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, printed in Strasbourg in 1504, bound in pigskin sometime thereafter, that Braganza left to the University of Notre Dame.

Gentle reader, in your charity, remember him.

John Nagy is an associate editor of this magazine.