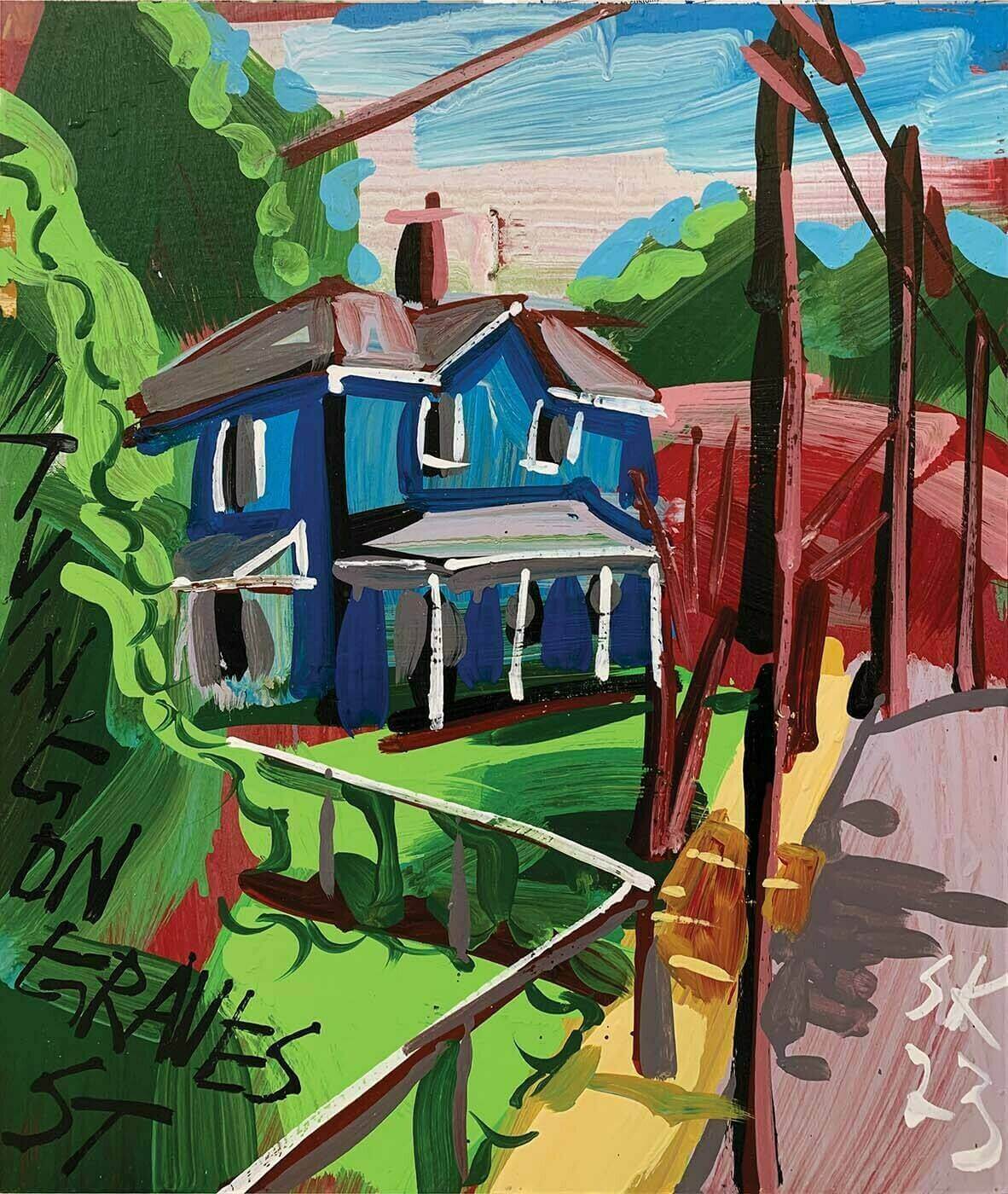

Before I could move into the upstairs apartment of a house on Graves Street in Charlottesville, Virginia, I first had to help the vacating tenants load their many coat racks and floor lamps, their croquet set, their loose pots and pans, their Steve Keene paintings and their creepy dolls into a U-Haul truck on a muggy August afternoon. They hadn’t started packing until move-out day. Laura and David, as I’ll call them, were an on-and-off couple moving to Pittsburgh. We were friends, though not so close that I joined them when they took a few hours’ break to go get a group portrait at Sears with the three other guys in their clique. I saw the portrait, an accidental masterpiece stylistically suspended between earnestness and irony, when they returned. They had posed like a family, arranged according to studio doctrine, seated and standing in tight formation at different heights. David’s eyes were barely open. Laura was in front, looking straight into the camera in her aviator sunglasses. I think she was hungover. As we kept packing and loading, they debated which of their group the photographer had mentally designated as the dad.

Even with the help of everyone in the house, including two guys I’ll call Sam and Nick, friends of mine who were in the portrait and who lived in the downstairs unit, we didn’t finish until after dark. And from the look of the loose, unboxed arrangement of things in the back of the truck, I doubted our packing job would survive the first turn onto Interstate 64.

To some people — mostly well-educated white people in their 20s, like everyone who inhabited the Graves Street house at the time I did — Charlottesville was known as the Velvet Rut. It was a good place to work a light schedule and start a band. Or work a light schedule and talk about starting a band. Or spend all day playing backgammon on a coffee shop patio and all night playing foosball in a dingy sports bar, as I did for an entire summer. Like other rural college towns, Charlottesville does a booming trade in charm and nostalgia. These things are easy to sell, so it can be easy to get by, unbothered by the split-knuckle competition that people visit Charlottesville to escape. The high strivers leave town right after graduation. If you’re young and talented but averse to the meritocratic struggle for dominance, you can stick around and rest secure in your potential. There’s no rush to go out and prove yourself. You have plenty of time.

Until it occurs to you that you don’t. You reach some birthday, or you want to cash in on your degree, or you want kids or to quit drinking, and you realize you can’t do that there. It’s as if a bell rings — though it doesn’t ring for everyone, and it’s possible to ignore it indefinitely. Laura and David had lingered in Charlottesville for a few years, heard the bell and were getting out. They were heading for graduate school and the city of Michael Chabon’s early novels, which enchanted them. I stayed in the apartment with them the night of the move — or they stayed with me. In any case, we had packed up their electric box fans, so we left the screenless windows open and sweated on top of our covers as inch-long mosquitoes feasted.

I moved to Graves Street after getting a doctorate in religious studies at the University of Virginia, a feat that netted me $60,000 in debt and a warped perspective on what matters to people, the result of having written a 300-page document for four idiosyncratic readers. The previous six months had been a dead sprint to finish my dissertation. Once I defended it, I had no job and no plan for what to do next. I ended up deciding to quit smoking. Moving into the house, where I had already spent countless evenings drinking PBR and playing Mario Kart in a purple-painted living room, was the next step in my campaign of self-repair. If I was going to get a teaching job, I would need to get in better mental and professional shape.

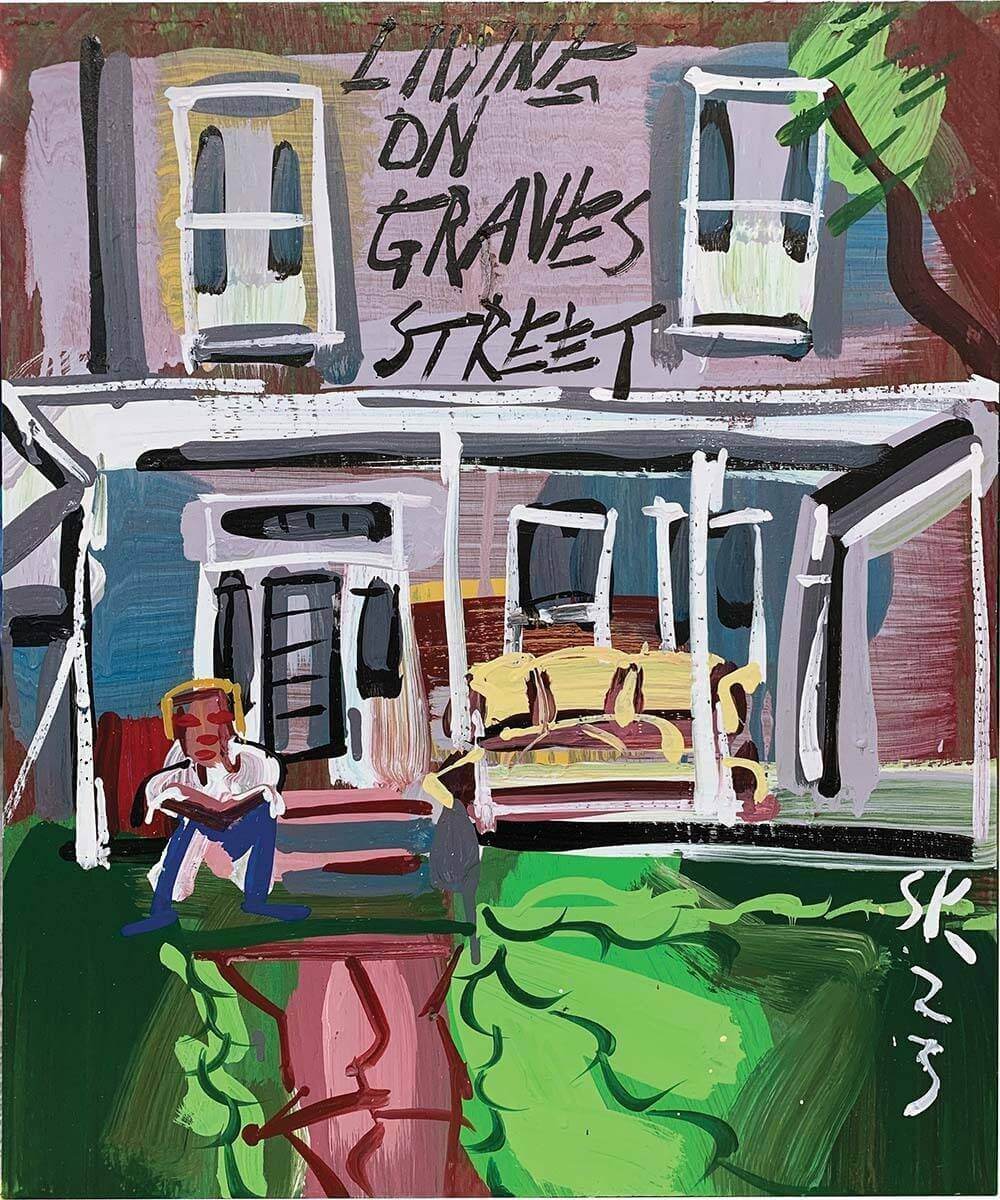

The house needed repair, too. It was clad in synthetic brick you could scratch away with your fingernail. The porch had a low railing, its rotting wood painted white. Upstairs, my kitchen, an addition I assumed was built when the place was divided into the two apartments, sloped dramatically away from the house and seemed in perpetual danger of peeling off altogether and collapsing into the back yard. Two bushes in the front yard near the sidewalk had been neglected long enough to become nearly as tall as the house itself. A small rosebush in a corner produced a few pink blooms. It was a short walk to the brick-paved downtown pedestrian mall’s antique shops, gelaterias and Virginia-gentleman clothing stores stocked with bowties and khakis embroidered with foxes and dachshunds. You just had to cross a bridge that spans the railyard. Because the house was close to the tracks, the parties we threw on our porch drew crudely tattooed young hobos and hitchers who heard the revelry and came on up.

Before and after I lived there for one year in the mid-2000s, the house was a dwelling of last resort for people who had first come to town to study at the university but after a few years wanted to live just far enough away from it that they could pretend the university didn’t exist. My kitchen had been someone’s bedroom for a while. At one point, a married couple had slept in the pantry downstairs, their mattress crowding the baseboards. But when I lived there, the place was relatively quiet. It was just Sam and Nick, their calico cat who spent half her time outdoors, my roommate and me.

Sam was my gateway to meeting Nick and Laura and David and countless others. I had met Sam about five years earlier, when he was working on a master’s degree in English and talking about the foreign service exam. He anchored himself with routine: a T-shirt and jeans over steel-toed boots year-round, weekend breakfast at the same diner. On Sundays he and I did the Times and Post crossword puzzles together on a coffee-shop patio, each of us working on one then switching when we got stumped. Once a month, we’d take on the cryptic crossword in Harper’s Magazine. We got to where we could solve it in about an hour.

At some point, Sam left Charlottesville to test his fortune in New York. He sublet a room in Jersey City, applied for jobs in publishing and ended up watching a lot of Dr. Phil. After a year, he came back to the Velvet Rut and moved onto Graves Street. By the time I moved in, as we both approached 30, he was selling Asian furniture at an antique shop and spending hours reading James Joyce or George R.R. Martin over pints of Guinness in the basement bar of a restaurant across the tracks.

For the first few months, I had a part-time roommate, an ex who had moved away but came back a few days a month to do research for her dissertation. She wasn’t one of us, in part because she knew what was next for her: a job in Washington, D.C., and marriage to a corporate attorney. I was cold to her. I resented her sitting on my secondhand velour couch and watching TV. I resented her conviction that the Iraq War was just. I resented her goat cheese in the refrigerator. I went to her wedding on New Year’s Eve — as far as the IRS was concerned, they had been married all year — but came home before midnight.

In my early days living in the house, I dismantled the leaky kitchen faucet and spent a dollar on a new valve for it. I solved the mosquito problem with inexpensive screens I could wedge between sash and sill. I reversed the refrigerator door so the sloping floor would keep it closed. I helped the guys downstairs clear rotten stumps from the yard.

These minor acts of improvement gave me an inordinate sense of accomplishment; they earned me the hard moral capital I needed for my more speculative work of applying for jobs. Week after week, I sat in a clean-swept room at the front of the house with the windows open and researched the departments that had posted job ads. I needed to figure out which courses to tell them, in my application letter, I would be eager to teach.

Eventually, I got a part-time job as a parking lot attendant right across the street from the university. Nick worked there. So did the guy who became my roommate after my ex got married and cleared out. I also went back to making sushi at the Japanese restaurant where I had worked off and on for five years. The restaurant was in a shopping plaza — its neighbors included a greasy seafood place and a laundromat — that belied the moody atmosphere inside. The only light came from tiny lamps hung above each table from the high, unfinished ceiling. A black-and-white school of fish, painted in Steve Keene’s jaunty strokes, adorned the walls.

The place was also a music venue. Indie rock and goth bands played in the basement, with acoustic acts offering lighter fare in a corner of the dining room. On weekend nights, pinned and mohawked punks coming in for a show would hold the door for middle-aged couples who had just finished their sashimi samplers and were heading home. Nick booked shows for a while, and Sam tended bar. In the year I lived on Graves Street, we and our friends occupied a booth most nights, filling the tabletop with steel cans of Sapporo and blue-glass dishes of edamame as we argued about music and fretted about John Kerry’s electoral chances.

To legitimate myself as a scholar that year, I begged a title and office at a research institute where earnest Christian doctoral students gathered around a conference table to discuss Alexis de Tocqueville over deli sandwiches. In October I started dating a woman named Ashley I met there. She was the part-time receptionist and, after stints in publishing and high school teaching, was preparing for a third career in academia. She sat on the edge of her desk chair in Mary Tyler Moore blouses and chunky plastic jewelry and fielded the institute’s rare phone calls while she read literary theory. One afternoon when everyone else in the office had gone across Grounds to hear David Brooks lecture at the institute’s invitation, I came out to flirt with her. We had our first date a week later.

The first time Ashley came to the house, she frowned at the shabby staircase with black-rubber treads leading up to my apartment and recoiled at the bare lightbulb on my bedroom ceiling. My room was unkempt, with clothing and books piled haphazardly, and it was cold — the baseboard heating was barely worth turning on. A garish, three-foot-square oil nude rendered in yellow, green and purple — a gift from the artist, who had disavowed it — hung over the bed, which had no headboard.

“I’m just going to focus on this chair,” she said while facing the one item I owned that might indicate I was safely bourgeois. The round, soft-sided Ikea armchair in the corner had a recently laundered chartreuse slipcover and an orange pillow on it. I didn’t tell her that a month before, on a weekend when Laura and David came back from Pittsburgh to visit and everyone was up drinking, I had awakened to find the chair soaked in urine. No telling how it happened. I refused to accept the likeliest narrative — that I had done it during a drunken sleepwalk — on the evidence that the seat cushion was still flipped up, and I was raised better than that. Soon after Ashley came over that first time, I got a light fixture to cover the ceiling bulb, tidied up the room and bought flannel sheets and a space heater. She started coming over more often.

Sam and I spent Thanksgiving, just us, at the house. Bad weather kept me from going home to Buffalo; he didn’t want to deal with his family in Northern Virginia. I hovered over Sam’s shoulder while he sat cross-legged on a plastic chair in his bedroom playing video games all afternoon. An 8-by-10 of the Sears studio portrait taken on the day Laura and David packed up hung on a wall nearby. I cooked steaks and potatoes for dinner and heated up a Mrs. Smith’s pumpkin pie for dessert. It was as domestic as I had ever been. The academic job market, and the threat that I would once again get no offers, defined the distant horizon of my concerns. But as more pieces of a decent life in Charlottesville came together — work, friends, a promising new relationship — I found I was settling in.

The Japanese restaurant was sold in December and closed right before Christmas. I think the owner was tired of 100-hour weeks and the stifling smallness of the town. He planned to visit family in Japan. After that, he didn’t know. The new owners planned an extensive renovation. There would be new staff, a new menu and new entertainment, karaoke, in the basement. We couldn’t go back.

The only light came from tiny lamps hung above each table from the high, unfinished ceiling. A black-and-white school of fish, painted in Steve Keene’s jaunty strokes, adorned the walls.

One Friday morning in February, still in bed, I got a call that I saw was coming from the unheralded college in northeastern Pennsylvania where I’d had an on-campus interview earlier in the week. I knew it was a job offer, but I wasn’t ready for that conversation, so I didn’t answer. The college’s vice president emailed me a half-hour later with the formal offer. I called back that afternoon to express formal enthusiasm about the job and ask for a week to decide whether to take it. I forwarded the email message to Ashley and added, “Well, there you have it.”

There was no question; I was going to take the job. It was exactly what I had spent the previous seven years preparing for, and it was the only one I was likely to get offered. One of my professors jumped up and down when I shared the news with him. But I needed the week to make sense of the fact that I would be moving away from everyone and everything I knew, away from the Velvet Rut and into an economically blighted former coal-mining region to teach a heavy load of intro theology to students who resented having to take courses on such a useless topic. As my former boss at the Japanese restaurant sang during his weekly acoustic set, in a song called “I Hate Charlottesville,” Yes, this is a town to dream / Forrr-ever. My dream there was about to end.

Later that week, when another of my professors parked his new Volvo S40 in the lot where I worked, he told me I didn’t have to take the job. This seemed a ludicrous temptation — who was I to presume I was meant for a higher place in the academic status hierarchy? Many are called to graduate school, and few are chosen for the tenure track. Shouldn’t I be grateful to be among the elect? Friends did their best to put a positive spin on the impending move. One mentioned how she had enjoyed the rugged beauty of the region’s hills, dotted with abandoned factories, while driving through on the interstate.

By Wednesday, I was still holding back. I emailed a genial member of the department to ask him how the college supported research and writing. He assured me I’d be able to accomplish what I wanted. I met another close friend for coffee, one who had studied at a different college in northeastern Pennsylvania, to talk things through. He told me about his landlord there who thawed the pipes in winter using a hairdryer. He told me about a guy who stood on a street corner and once ostentatiously exposed himself while my friend drove past. He also told me how much he grew, personally and intellectually, while he lived there.

That same afternoon, Ashley got some news — she was accepted into a top-ranked graduate program in California, with full funding. While she walked home from work, she spoke on the phone with a professor who said her application was “pure pleasure” to read. The acceptance felt like acceptance. It validated her as the smart person she had tried to be ever since she began reading Harper’s in her teens. When she got the call, she was still waiting to hear from a program on the East Coast, but it wouldn’t matter. When you get an offer like that, you say yes.

We had tickets to see the alt-country singer Neko Case perform that night. Everyone I knew was going to the show; we chattered about it in chance conversations at the parking lot and on the Downtown Mall. We also talked about Sam, who had just returned from a monthlong trip to Bali, where he and his boss had gone to buy inventory for the antique shop. Midway through his trip, Sam had fallen through a missing section of sidewalk into the drainage ditch below, shattering a bone in his foot. After a 30-hour trip home that crossed a dozen time zones, he visited a doctor the afternoon of the show to get an MRI and be fitted with a boot. But he wouldn’t miss Neko.

When Ashley and I drove to the show, we sat in the parked car for a few minutes as the sidewalk filled with people heading into the venue. The continent-wide distance about to open between us seemed far off and abstract, but it demanded to be acknowledged.

“I don’t want to break up over this,” I told her.

“Neither do I.”

We promised each other we’d figure something out. We had time to figure it out.

As we waited in line to get inside, Ashley saw one of her mentors who had inspired her to apply to graduate school, a long-haired gray eminence whom I knew from his writing and from parking his third-generation BMW 5-series. When we saw him that night, as I recall, he was incongruously wearing a leather motorcycle jacket. Ashley told him the news, and he offered congratulations, tempered by assurance that she would get in elsewhere, too, as if she needed to. Then we went inside. When we caught up with Sam, he was holding himself up on crutches by the bar, telling stories about Bali and getting drinks bought for him.

Onstage, Neko wore a Penn State T-shirt. It calmed my trepidation about the future for a moment. She looked cool in navy blue, with the Nittany Lions logo across her chest. Maybe, by transitive logic, that meant Pennsylvania was cool. Maybe that meant it was OK for me to move there.

When she got the call, she was still waiting to hear from a program on the East Coast, but it wouldn’t matter. When you get an offer like that, you say yes.

The show let out, and my friends went on to another bar. Ashley and I decided we’d call it a night and returned to my apartment. As we walked up to my door on the side of the house, I saw Nick’s and Sam’s cat lying on the stone walkway, dried blood on the ground by its open mouth. It was dead. I couldn’t tell what had happened. Hit by a car? Fell off the roof? Lost a fight? I sighed, scooped up the cat with a shovel and moved it to the edge of our yard. I’m not sure why, other than a walkway was no place for a dead cat. In the porch light, the stark fact of its death jarred me. The grass by the fence seemed, I don’t know, a more discreet, more respectable resting place.

I called Nick, who was at the bar with Sam and everyone else. I wanted him to know and asked him to break the news to Sam. Even though Sam wasn’t especially fond of the cat, I suspected he wouldn’t take it well.

He didn’t. An hour or so later, I heard the guys come home. I brought down a bottle of Jameson’s leftover from Thanksgiving to talk with them on the porch. They were already into what was left of the Johnny Walker Black that someone’s mysterious, fur-wearing girlfriend had brought over before Sam left for Bali. Nick sat on the sagging, weather-beaten couch, Sam on the stoop, ripping through Camel Lights, his stubbled face hanging limp. We drank the whiskey in the cold as Sam cried intermittently.

Then he stood up, yelled something guttural and kicked at the railing, planting with his booted foot and striking with his good one. He kept slipping, falling down to the floorboards, getting back up, kicking. I stood on the walkway with a plastic cup in my hand, watching, unsure what to do. After another fall, Nick dragged him away from the railing by his shoulders and shouted, “Enough!”

It wasn’t enough. Sam got back up and grabbed the railing with both hands. He shook it back and forth, grunting, until it cracked free of the pillars. He chucked it into the yard. Then he grabbed the next section of railing and pulled and kicked until it broke off, too. And the next, and the next. He threw the final sections into the street, hollering. I went upstairs to bed.

The cat went into a trash bag inside a blue recycling bin next to the porch for a couple weeks until the ground thawed and Nick could bury it. When our landlord saw what had happened, he asked whether anyone was hurt when the railing collapsed. We said no. He never replaced the railing.

More than a decade passed before I talked to Sam about the incident. He told me that moment was his nadir, as bad as his worst depression. “Nothing was good,” he said. The cat’s sudden death bothered him, but it was only the spark that ignited a whole pile of explosive material: the trip, his job, his inability to figure out what to do with his talents, and a lot of alcohol. He came to see his act symbolically; it was the ruin, he said, of “the transitional space between home and the tyranny of the outside world.”

We were all in transition. It was just a question of how long we’d each been in that condition, and how we dealt with it. After missing all the checkpoints to respectable adulthood, I had suddenly found myself at the border, valid papers in hand. All I could think to do was pause dumbly and resign myself to shuffling across. I had been under similar pressures as Sam — the constant collision with the limits of my ability in graduate seminars, my unfavorable comparisons of myself to pompous poseurs, my financial exigency, academia’s shameful willingness to exploit adjuncts rather than hire full-time faculty, the whole country’s willingness to wage an unjust war in Iraq.

I should have rebelled. I should have wrecked my house, smashed all the windows, uprooted the shrubs a hundred times over. But I’d missed my chance. I had mistaken acquiescence for prudence and the way to professional success. Maybe if I had raged against the forces back then, pushed back and made space for myself, I would have picked up the phone immediately when the college’s vice president called and jumped on the bed all morning, danced and spun at the concert, worn a Penn State T-shirt till it fell in funky rags from my flesh. Or I might have said no to the job, no to the distance that chasing careers would put between Ashley and me, and followed her west. But I had always turned the pressure inward, cramping and cracking my substructure, and when I finally got what I’d always said I wanted, I just didn’t have the strength.

You have to get out of ruts, velvet and otherwise. You have to cross the checkpoint. You have to get off the porch; you can’t live there. But maybe you didn’t have to give in to the tyranny. I don’t know. I hadn’t tried to find out.

They threw me a going-away party in July. In a series of pictures Ashley took that night, a handful of people sitting on the porch swells to dozens out in the yard. Friends drove in from out of town to toast my job and my decisive exit from Charlottesville. A hobo who said he was from Arkansas came up from the tracks and ate an entire stick of butter while he reminisced about other butters he had enjoyed in his travels. He slept on the porch sofa that night.

Sam moved into a place of his own that fall. Nick stayed. I went to Pennsylvania, Ashley went to California, and another parking lot attendant took my spot in the house.

More than a dozen years later, Ashley and I walked by the house while visiting friends who had made good lives in Charlottesville. I had quit the job in Pennsylvania and followed Ashley when her career took her to a university in Texas. Our week in Charlottesville was warm and muggy, kind of like the day I moved in. When we walked by the house the first time, on a Sunday evening, a young family with three little kids was sitting on a church pew and metal chairs on the porch. A thought occurred to introduce myself as a former tenant and tell the story of why the porch had no railings. I thought better of it; we had become nostalgic alumni, and it didn’t seem fair to impose that on these nice people’s home life. We kept moving.

I started wondering who they were — what kind of person would want to live there? They looked earnest. I imagined them as evangelical missionaries living in an intentional community. Or maybe shape-note singers. A few minutes later, we saw the father walk down the alley with a child on his shoulders.

Guided by a mad belief that his house held the secrets to my soul, I walked past it several times. One weekday morning, three men were out on the porch. Did they all live there? Or was the place still a social hub? I was too far away to hear what they were talking about, too afraid to get any closer lest they take me for a stalker, which I was.

The next day I noticed that the overgrown bushes had been tamed into plausible trees. The rosebush was gone. All the windows were closed, and an air-conditioning unit hummed on the ground outside. A stack of firewood stood next to the porch. A new addition to the back of the house filled the space under my old kitchen: All it needed was siding. There was an Audi parked in the driveway.

Jonathan Malesic’s essays have appeared in America, Commonweal, The New Republic and The New York Times. His 2022 book, The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, is being translated into eight languages.