In the fall of 2020, a Notre Dame student named Maggie O’Brien reached out to me with concern about our campus landscape; she had become aware that, apart from statues of Mary, public art at the University includes almost no representations of women. O’Brien intended no slight against the Blessed Mother. “I love Mary,” she wrote, “and I love that our school is named after such an important woman.” Depictions of Mary, however, tend to emphasize only the maternal and devotional aspects of women’s lives. How powerful would it be for women on campus today, she asked, if campus art and architecture acknowledged the broad range of women’s abilities and contributions to Notre Dame and to the world? Would it be possible, as a first step, to establish a memorial to the first women to come to Notre Dame?

O’Brien’s questions echo larger American debates over public monuments and the messages they send. These conversations are often more polarizing than they should be. Reflecting on who is represented — and who is not — in collective memory should prompt us to study the past open to the idea that beliefs and sensibilities change over time. Few people today, for example, would agree with Rev. John W. Cavanaugh, CSC, then the University’s president, when he explained women’s absence from public spaces in 1916: “Someone has asked why the world has never erected a monument to any woman.” The answer, he said, “is that every great man that has ever lived is himself a monument to some good woman.”

Cavanaugh was speaking at the funeral of Sister M. Aloysius, CSC. Born Honora Mulcaire in Ireland in 1845 — the first year of the Irish Potato Famine — Sister Aloysius entered the Sisters of the Holy Cross in 1873, one of many young Irish women for whom religious life in America offered an escape from dismal prospects in her native land. In Cavanaugh’s estimation, Sister Aloysius had such ability that “she might have been president of the United States.” Instead, she taught Notre Dame’s “minims,” or grammar school students, for over 40 years in the Main Building and at St. Edward’s Hall. Cavanaugh calculated that only the University’s founder, Rev. Edward Sorin, CSC, had given more years of service to Notre Dame than Sister Aloysius had; moreover, only he could have rivaled her in zeal, enthusiasm and talent.

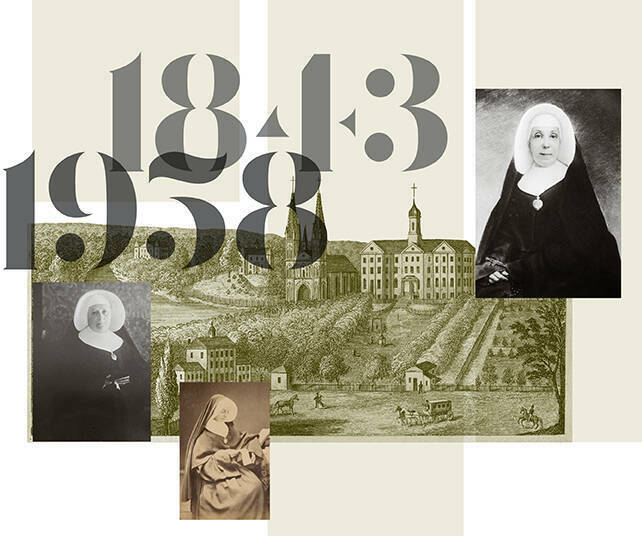

Sister Aloysius was one of hundreds of Holy Cross sisters who lived and worked on campus between 1843 and 1958. (Their story is distinct from, though intertwined with, those hundreds of Holy Cross sisters who lived and ministered at Saint Mary’s College, and who continue to do so today.) Cavanaugh knew how integral Holy Cross sisters would continue to be to the success of the institution he led. “When the history of Notre Dame is completely written,” he predicted, “no chapter in that beautiful and brilliant story will be more heroic than the part the Sisters have borne in the work.” The record of their services would never be “inscribed on monuments of brass or marble,” but etched on “the hearts of grateful men” and “written in the Books of God.”

Cavanaugh was neither the first nor the last Holy Cross priest to admit that Notre Dame could never have functioned as an institution, let alone developed into a great university, without the unsubsidized labor Holy Cross sisters provided for over a century. Yet their story remains largely unknown, and, apart from two in a series of 30-odd small plaques on the “Wall of Honor” on the Main Building’s ground floor, is not commemorated on campus. It is conspicuously missing from the monument that occupies a central place in Notre Dame’s collective memory: the Founder’s Plaque.

Standing near the Log Chapel, overlooking St. Mary’s Lake, the plaque is inscribed with an excerpt from a letter Sorin wrote to Rev. Basil Moreau, CSC, on December 5, 1842, soon after he arrived on campus after an arduous journey from southern Indiana, where he and six Holy Cross brothers had begun their American mission a year earlier. Two paragraphs of that letter are often quoted:

Will you permit me, dear Father,

to share with you a preoccupation

which gives me no rest? Briefly, it is

this: Notre Dame du Lac was given to

us by the bishop only on condition

that we establish here a college at

the earliest opportunity. As there is

no other school within more than a

hundred miles, this college cannot

fail to succeed. . . . Before long, it

will develop on a large scale. . . . It

will be one of the most powerful

means for good in this country.

Finally, dear Father, you cannot

help see that this new branch of your

family is destined to grow under the

protection of Our Lady of the Lake

and of St. Joseph. At least, this is my

deep conviction. Time will tell if I am wrong.

It’s no wonder these words are so familiar to the Notre Dame family. I love to visit the Founder’s Plaque, especially in winter, to marvel at the audacity of Sorin’s vision. At the same time, I am all too aware that, as historian Eric Foner observed, “Historical monuments are, among other things, an expression of power — an indication of who has the power to choose how history is remembered in public places.” Monuments oversimplify; often they distort or omit. In the case of the Founder’s Plaque, the space between what appears to be the last two paragraphs of a prophetic letter obscures a forgotten and complicated aspect of Notre Dame’s history.

Translations of the original letter reveal what has been redacted. The phrase “means for good” is not followed by a period, but instead by a comma, after which Sorin goes on to mention Holy Cross brothers and, significantly, the sisters: “. . . once the Sisters come — whose presence is so much desired here — they must be prepared,” he wrote, “not merely for domestic work, but also for teaching; and perhaps, too, the establishment of an academy.” Within a year, four Holy Cross sisters did arrive from France: Sister Mary of the Heart of Jesus, age 19; Sister Mary of Bethlehem, 45; Sister Mary of Calvary, 25; and Sister Mary of Nazareth, 21.

Before long other French men and women joined the Holy Cross mission in Indiana — and Sorin needed them desperately. Also elided from the Founder’s Plaque is an important qualifier to Sorin’s prediction: The college would succeed, “provided it receive assistance from our good friends in France.” Here Sorin meant money and vocations, and he regularly traveled to France to secure both.

One French sister who made a notable imprint on Notre Dame was Mother M. Ascension, CSC. Born Mathurin Salou in 1826, she had been “electrified” by Blessed Basil Moreau’s preaching and entered his fledgling congregation at Le Mans in 1845. Inspired by his account of mission work in Indiana, Salou longed to serve there, but evidently her superiors, “detecting the rare qualities of mind and heart with which she was endowed,” wished to retain her as a future leader at the French motherhouse. After meeting Salou, however, Sorin arranged for her to join him at Notre Dame, where she became one of his key collaborators and supporters, serving for decades as either novice mistress or local superior to the sisters at Notre Dame. At the celebration of her golden jubilee, Mother Ascension was extolled for helping to build “a university in which there shall never be any divorce between Science and Religion.” When she died in 1901, mourners eulogized her as “the last of [Notre Dame’s] pioneers.” Mother Ascension may have lived “in quiet obscurity,” but she had been second only to Sorin in “achieving the present greatness of Notre Dame.”

Sorin’s keen eye for talent also redirected the vocational path of Eliza Gillespie. In 1853, the 29-year-old woman was traveling with her mother from Ohio to Chicago, where she intended to enter the Sisters of Mercy. The pair stopped at Notre Dame to visit Eliza’s brother Neal, one of Notre Dame’s first graduates, who would soon join the Congregation of Holy Cross. Encountering Eliza Gillespie near the University’s front gate, Sorin sensed her intelligence. (“Eliza should never marry,” another priest had warned her mother. “There is not a man alive who is her mental superior.”) Sorin declared on the spot that God was calling Gillespie to enter the Sisters of the Holy Cross instead. After a few days of prayer and a visit to the Holy Cross sisters at Bertrand, Michigan, where they had established a novitiate in 1844, Eliza agreed. She received the name Sister Mary of St. Angela and, after her novitiate in France, became the head of the academy at Bertrand and remained in this role when it was moved to the present location of Saint Mary’s College in 1855. Apart from the four years she devoted to nursing during the Civil War, Mother Angela spent most of her religious life closely tied to Notre Dame, where, along with Mother Ascension, she was regarded as one of Sorin’s “two hands.”

Mother Angela and Mother Ascension figured prominently in a controversy that, though well-documented in congregational archives and recounted in official histories, is not commonly known. The source of the conflict is foreshadowed in the elided sentence about Sorin’s need for sisters. When the priest wrote that they must be ready “not merely for domestic work,” he no doubt meant it. He supported the sisters’ efforts to open an academy at Bertrand, and he purchased the property for its new home closer to Notre Dame. But Sorin’s support for their educational work extended only so far, and once it started to interfere with his own ambitions for Notre Dame, it would reach its limit.

In a letter dated February 10, 1872, Sorin complained to Archbishop John Purcell of Cincinnati that up until “some ten or eleven years ago” Holy Cross sisters on campus had performed “all the work reserved to females.” The departure of many of them for Civil War service had forced him to hire outside help, a fix he apparently had hoped would be temporary. Not so. “Since the close of the war,” he told Purcell, “the Sisters have multiplied their own houses.” Consequently, they “have been unable to give Notre Dame but half the number of hands really required,” thereby creating “a permanent insecurity” and “a permanent expense.” Sorin proposed a solution: He would establish a new congregation entirely devoted to domestic work at Notre Dame. He envisioned outfitting the new congregation in “the cap and collar of your Sisters of Charity” and asked Purcell to help recruit candidates, so that the new order could grow large enough to supplant both hired women and the Sisters of the Holy Cross in service at Notre Dame. By forming an order “to supply our own wants,” Sorin estimated that Notre Dame could save $5,000 annually.

Sorin’s threat alarmed the sisters at Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s. Among those who protested was Sister M. Compassion, who had been born Margaret Gleason in Ireland and had served at Notre Dame in its early years. Sister Compassion implored Sorin to recall the firm bonds between the sisters, priests and brothers of Holy Cross and to abandon his plans to form a separate female congregation. “I for one and an Irish Sister, too, am much opposed to the separation,” she wrote, “and as much as I love St. Mary’s I would be willing to spend the rest of my life at N.D. if by so doing I could preserve the Union.” Beyond tearing the Holy Cross family apart, she reminded Sorin, his scheme could spell disaster for the sisters. “Now Reverend Father, we are not yet ESTABLISHED and you speak of getting up another Community. . . . It is a serious step and God only knows what the end will be.” The Holy See had not yet extended permanent recognition to the Sisters of the Holy Cross; Sister Compassion understood that Sorin’s machinations would make that possibility more remote.

Sorin’s power play was one chapter in a complicated story of how the Sisters of the Holy Cross earned the ability to make their own decisions about their ministries, their finances and their leaders.

Sister Compassion, Mother Angela and other Holy Cross sisters developed a counterproposal, pledging to send enough of their number to supply Notre Dame’s domestic needs, even though it would require them to hire more outside help at Saint Mary’s. Sorin eventually agreed to a compromise that entailed opening a second Holy Cross novitiate at Notre Dame to prepare young women for domestic service. This move, he insisted, was necessary “to save our dear Congregation money, safety, and permanent help. To deny it now would be simply an act of stupidity or pure malice, looking to the ruin of Notre Dame.” He agreed that, as long as this “Annex to St. Mary’s” produced enough vocations to meet Notre Dame’s needs, he would not resort to forming a separate community.

Though this episode, which divided and hurt the sisters, does not reflect positively on Sorin, his behavior as the ecclesiastical superior of a group of religious women was hardly unique. Female congregations habitually struggled for autonomy while operating under obedience to priests and bishops who, to put it mildly, did not always have their best interests at heart. Sorin’s power play was one chapter in a complicated story of how the Sisters of the Holy Cross earned the ability to make their own decisions about their ministries, their finances and their leaders. A monumental step in this process was the sisters’ election of Mother M. Augusta Anderson, CSC, as their first American superior general in 1889. Mother Augusta, a nurse during the Civil War who helped negotiate the 1872 compromise, played a decisive role in securing the sisters’ autonomy — and permanent Vatican recognition of their constitutions in 1896. She had often tangled with Sorin along the way.

Independence did not change the sisters’ commitment to Notre Dame. The Vatican eventually ordered the Notre Dame novitiate to close — having two novitiates for the same congregation less than a mile apart was highly irregular — but the sisters continued to live and work on campus until 1958. At a Mass marking the final departure of the Sisters of the Holy Cross, Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, assured them that they and their predecessors would never be forgotten by Notre Dame’s administrators, faculty and students. “You have been,” he told them, “the golden threads woven forever into the tapestry of [Notre Dame’s] life.”

Rev. Arthur Hope, CSC, who had written Notre Dame’s official history and thus appreciated better than anyone the cumulative value of the sisters’ 115 years of service, delivered the homily at the departure Mass. Hope was also almost certainly the author of a remarkable essay, “The Sisters Depart,” published in the congregation’s Province Review, which he edited. He reviewed the sisters’ history at Notre Dame, referencing Sorin’s threat to establish a new community and Mother Augusta’s attempts to seek “emancipation from Father Sorin’s none too gentle tyranny.” Wondering “what . . . Notre Dame would have been without [the women’s] service,” Hope lamented that “a coming generation will forget the debt.”

And so it did — rather quickly. Perhaps the most consequential act of forgetting was committed by Rev. James Burtchaell, CSC, ’56. After his 1970 appointment as the University’s first provost, Burtchaell was at the center of negotiations, begun several years before, between Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s College about a merger of the two institutions. In December 1970, consultants hired by both schools released a plan that would have substantially integrated Saint Mary’s into Notre Dame but allowed it to retain a distinct identity. Burtchaell vehemently opposed the plan and the assumptions behind it. “What is needed,” he said, “is not the merger of two equivalent institutions but the incorporation of one into the other.” His reasoning was financial: Notre Dame’s budget was 10 times that of Saint Mary’s; Notre Dame had a sizable endowment, while Saint Mary’s depended on tuition. According to The New York Times, Burtchaell indicated that Notre Dame would go coeducational “with or without Saint Mary’s” but had extended the invitation to the college “because of the long history” the schools shared.

Had Burtchaell truly considered that long history, he would have remembered the sisters’ mammoth contribution to what Rev. James Burns, CSC, John W. Cavanaugh’s successor as Notre Dame’s president, called the University’s “living endowment” — the labor provided by its vowed religious. In that case, Burtchaell might have approached the sisters at Saint Mary’s not as supplicants but as partners from the past who would join him in building a new model for the future.

Burtchaell’s arrogance was only one factor that contributed to the decision, in November 1971, that the merger would not go forward. Soon Notre Dame announced it would begin direct admission of women to its undergraduate classes the following fall.

University historian Father Arthur Hope, CSC: ‘No human effort, however great and lasting, can recompense the Sisters of the Holy Cross for what they have done for Notre Dame.’

Those of us who believe there continues to be a place for women’s colleges — and who know how well Saint Mary’s educates its students in the Holy Cross tradition — may be grateful the planned merger did not succeed. Still, we can appreciate that its failure had consequences. One was that Notre Dame’s transition to coeducation was far rockier than it might otherwise have been. The merger had been designed to achieve a male-to-female ratio at Notre Dame of 3-to-1. After the University went its own way, that ratio the first year approached 17-to-1, creating a far less welcoming climate for female students and faculty.

As we celebrate this 50th anniversary of undergraduate coeducation, it is important to keep in mind that the women who enrolled in 1972 were not, by a long shot, the first women on campus. To return to Maggie O’Brien’s excellent suggestion, building a monument to Mother Ascension, Mother Angela, Sister Aloysius and the other female leaders who shaped Notre Dame in its early years would inspire both women and men on campus. It would also help the women of Saint Mary’s feel at home at Notre Dame, as they should.

What if the University went a step further and chose also to remember those Sisters of the Holy Cross whose names enter the historical record only glancingly? I think of Sister M. Bethlehem Desneux, one of the original four from Le Mans, who oversaw the dairy and chickens until she died in the cholera epidemic of 1854. Or Sister M. Agnella O’Sullivan, who worked in the Scholastic printing office for almost half a century. Or Sister M. Anthony Dooley, who lived on campus for 67 years, many of them spent mending and sewing for the campus community. Or Sister M. Claudine Lederle, who worked in the laundry and the infirmary between 1906 and 1918, when she died of pneumonia contracted while nursing sick students during the influenza epidemic.

The forgotten service of these women, and hundreds of other unnamed Sisters of the Holy Cross, highlights the stubborn realities that present themselves in the places where humans live and work. People need to be fed, nursed, clothed and cleaned up after — and the further down members of the community fall in the intersecting hierarchies of race, class and gender, the more likely it is these tasks will fall to them. The dynamics in most families and in American society, especially during this pandemic, confirm what I have learned from studying “essential workers” in the Catholic Church and its institutions. The more highly such work is prized in rhetoric, the lower it is compensated in reality — and the less likely it is to be remembered by future generations.

This hidden work is often performed out of love, or faith, or both. What about the God who sees and rewards all, especially the lowliest in this life, in the next? Doesn’t that hope cheapen or remove the need for repayment in this life? Many people suggest so. “Is there any lasting way Notre Dame’s debt can be paid?” Father Hope asked in 1958. “Thank God, in one sense, there is no way. An earthly payment, a temporal payment, there is none. No human effort, however great and lasting, can recompense the Sisters of the Holy Cross for what they have done for Notre Dame.”

Maybe Father Hope is right. Maybe the best we can do is trust that Sisters Agnella and Bethlehem and Claudine and the legions of women who labored so long at Notre Dame are being richly rewarded in God’s eternal presence. In this life, though, the very least we can do is take seriously another of Hope’s questions: “These Sisters of the Holy Cross who, even from an economic point of view, have given so much and asked so little, how shall we remember them?”

Historian Carl Becker once observed that history is what the present chooses to remember about the past. What if Notre Dame consciously chose to remember its forgotten women? What if it designed a more inclusive, plural Founders’ Plaque that acknowledged all those who made Notre Dame what it is today? What if the University modeled for the Church and the world how the remembrance of difficult facets of the past might help us imagine a new and better future?

Talk about a means for good.

Kathleen Sprows Cummings is Rev. John A. O’Brien Professor of American Studies and History and the director of the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism at Notre Dame. Her most recent book is A Saint of Our Own: How the Quest for a Holy Hero Helped Catholics Become American (University of North Carolina Press, 2019).