Required reading at the Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies’ annual summer conference included a comic strip. In this edition of Shoe, esteemed “Perfesser” Cosmo Fishhawk receives a letter asking him to weigh in on the question, “How do you think we can achieve world peace?”

The inquisitor has the courtesy to make this monumental task a little easier, enclosing a 3-by-5 card for the perfesser’s reply.

Several dozen leaders from global peace studies programs chuckle at the demand implicit in the punchline displayed on the screen in their meeting room at Jenkins Nanovic Halls. It’s a variation on a theme familiar to scholars in their idealistic discipline: Solve history’s most intractable problems and, please, be brief.

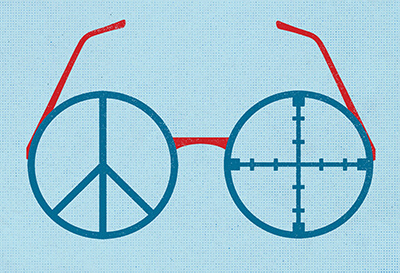

Illustration by Dan Page

Illustration by Dan Page

George Lopez, Notre Dame professor emeritus of peace studies and the founding director of the popular Summer Institute that attracts these peace experts to campus, turns the group’s attention to the index cards on their tables. “Your task for the next seven to 10 minutes . . .” Lopez begins, and the realization of their assignment spreads quickly. They’re going to have to distill their personal visions for world peace into the same space allotted to Perfesser Fishhawk.

That prompts some murmuring. (Professors, it turns out, generate the same bemused buzz as students when surprised with a pop quiz.) Whispered uncertainty about the parameters — Write on one side or both? Share answers? — circulates the room, along with laments about illegible handwriting and flares of laughter.

Instead of the promised seven to 10 minutes, Lopez speaks up after about three, sensing restlessness and diversity of opinion in the increasing conversation.

“I can tell nobody is on the verge of consensus,” he says, cutting through the crosstalk and getting to the point. “Sixty-five experts in the room, how do we achieve world peace?”

Answers illustrate that the unwieldy term “world peace” lacks a unifying definition, let alone common cause in how to get there, or agreement on whether it’s even possible. “Negative peace” is the field’s term of art for an end to violence, whether between nations, groups or individuals. “Positive peace” adds the notions of justice and equality to the requirements for a stable and enduring nonviolent environment. “Hegemon” refers to a powerful authority or political entity that imposes and preserves peace — “Pax Americana, that kind of thing,” Lopez says.

Some ideas outside the peace studies orthodoxy are floated as well. One conference attendee refers to the Israeli historian Yuval Noah Harari’s book Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, which argues that the threat of nuclear annihilation has served as a restraint on war since Hiroshima and Nagasaki — relative to the bellicose centuries of human history that preceded World War II. That is, more nuclear bombs, more peace.

“OK,” Lopez says. “How many people wrote that on their cards?”

Another table comes to a “world peace” accord only so far as to say, “surrender the wish,” the sentiment being that the concept is too multifaceted to be sought in any practical way outside the panels of a cartoon.

The prevailing realism in the room contradicts a common perception about peace studies, that it’s a naïve indulgence for intellectuals, a refuge for tree-huggers. An image of a hand-holding ring around a tree trunk appears on the screen during one presentation, acknowledging that reputation if only to refute it.

For his part, Lopez shrugs off that impression with reference to Kroc’s history of delving into the “nitty-gritty,” from its origins in addressing the 1980s “nuclear dilemma” to the faculty’s boots-on-the-ground engagement with conflict from Colombia to Chicago, and throughout Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

Examples abound of Kroc alumni on the front lines around the world: Zoughbi Alzoughbi ’89M.A., the founder and director of the Palestinian Conflict Transformation Center in the West Bank. Rosette Muzigo-Morrison ’93M.A., a legal officer at the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Myla Leguro ’10M.A., program director for Catholic Relief Services’ interreligious peacebuilding programs in Egypt, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Niger, Nigeria and the Philippines.

Achieving and maintaining peace, in other words, is a constant fight across multiple fronts on an increasingly interconnected globe. Conflicts spill across borders and shorelines and information networks with violent repercussions. To stem the bloody tide requires face-to-face confrontations with systemic causes and combatants.

“There’s been a kind of an idea of peace as something quite static, that peace is what happens when it’s all finished, when the action is over. When the fat lady sings, that’s peace, you know,” says Caroline Hughes, the Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, C.S.C., chair in peace studies. “Peace is actually a very dynamic thing.”

Illustration by Dan Page

Illustration by Dan Page

Lopez boils it down to this: “You don’t put Gandhi, Mother Teresa and St. Francis around the table to make peace. You put murderers, scoundrels and liars, because they’re the people who’ve been involved in the violence. They can help craft the first stage, and the peacebuilders help go from there.”

For participants in the weeklong Summer Institute, “go from there” is why they’re here. Since it began in 2008, the workshop has become an annual gathering place for peace scholars to shape or sharpen their particular curriculum. From among the schools represented — 12 from the United States, 10 from abroad — are leaders of programs both new and well-established who are interested in adding an advanced degree or a new concentration.

They come to Kroc because, for years before Lopez initiated the summer conference, schools interested in starting or strengthening their peace studies offerings often asked Notre Dame’s experts to come to them.

“We decided, let’s bring people to us,” Lopez says. “Because, I guess it’s not a very academic phrase, but we had all the big stallions in the corral.”

Giants in the field like John Paul Lederach, professor emeritus of international peacebuilding. Lederach pioneered the concept of conflict transformation, which focuses on understanding the social structures and relationship dynamics that lead to violence. Addressing root causes, the theory goes, better prevents conflict and, when conflict does arise, promotes a more lasting peace than just negotiating an end to fighting.

Another towering figure was the late John Darby, a native of Northern Ireland. Darby led the development of the Peace Accords Matrix, which analyzes the factors that lead to the success or failure of conflict resolution agreements. In 2016, Kroc assumed responsibility for monitoring the real-time implementation of Colombia’s peace accords using the matrix, the first university-based research center to play such a role. It was the culmination of decades of Kroc experts’ work in the country and a testament to the international influence of the matrix.

Lopez rattles several more names off the top of his head, a small sampling of Kroc’s roster of 30 core faculty members that makes it the largest of seven institutes under the umbrella of the Keough School of Global Affairs. In addition to the professors with “peace” in their titles, the list includes experts in theology, sociology, anthropology, psychology, law — a Venn diagram of disciplines overlapping in their proficiency in promoting nonviolence.

With its deep reservoir of resources and respected researchers, Kroc’s reach extends around the world. “From South Bend to South Sudan,” as Asher Kaufman, the institute’s John M. Regan director, puts it — and he’s referring to a single faculty member, David Hooker, whose work alone spans that distance. Most of the schools represented at the Summer Institute cannot match Kroc’s scope, but each contributes their own piece of what Lopez calls “the peace puzzle,” which no professor or program could assemble alone.

“You don’t have to range from nuclear disarmament to gang violence and cover everything in between,” Lopez says. “Our mission is to help you do what you might do best” and leave the challenge of achieving world peace to Perfesser Fishhawk.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.