Illustration by David Pohl

Illustration by David Pohl

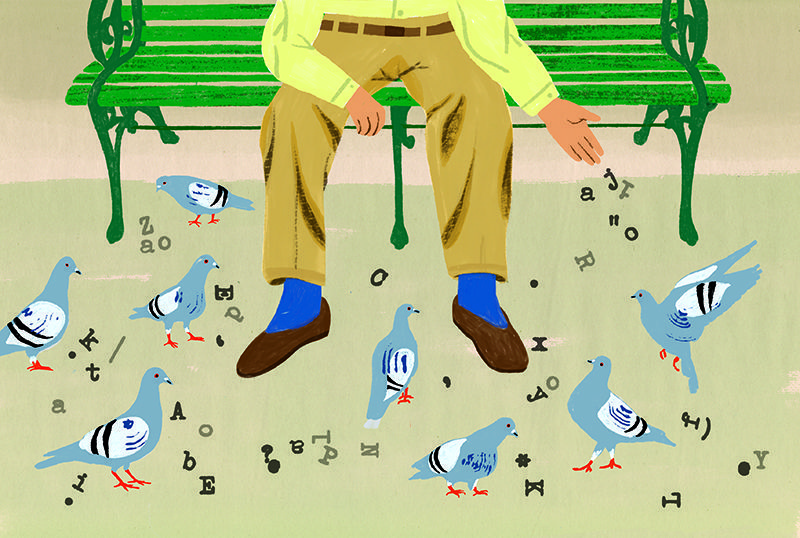

A pair of pigeons watch me as I stoke their feeder. Like nonviolent “insisters,” they perch in place and wait to be acknowledged as pigeons, not annoyances. They practice social distancing. After I leave, they feed until they’ve had their fill, then flex and taxi for a slow flight beyond leftover seeds and houses and neighborhoods where people are dealing with life and death and everything in between.

Here in western Pennsylvania we’re months past lockdown, but the virus has spiked anew. The wearing of masks is again required as well as six feet of space between people in public places. When the restrictions first became part of daily life, I wanted to be miraculously exonerated so that I could live what was, after all, my life. Gradually I came to realize that this was a real emergency. Wanting to live as if you were singularly immune was both naïve and dangerous to yourself and others.

Leaving aside those who believe in their own immunity (and those who have to provide such public necessities as health care, food and transportation), I see basically two ways to react to what is unignorable.

The first reaction is to become a stoic and “tough it out.” Stoics try to live as well as they can in semi-incarceration. They accept the merciless fact that being human means being subjected to what is beyond their control. Distractions are possible, of course, but the longing for the life they lived only intensifies over time. The things that sustain them are hope and determination, interrupted now and then by pent-up impatience and some choice occasional cursing.

The second possibility lies in the power of the imagination. Only the imagination permits us to transcend the circumstances in which we sometimes find ourselves. This is not escapism. It is what enables us to feel or see or hear what defies time and space and puts us in touch with our humanity. It may involve remembering an unexpected kindness in which you were the beneficiary. It may be the recollection of an insight or a statement that suddenly connected you with a truth that made everything else secondary.

This morning, for example, I suddenly remembered an incident that happened when I was 6 years old. I was in Watertown, New York, with my father. He was on a business trip to the Thousand Islands, and he had taken my brother and me with him. We were walking together on a dock, and I began running. I had only taken a few steps when I tripped and fell into 20 feet of water. I had not yet learned how to swim, and my father was not able to swim. All I remember now was sinking slowly until I felt myself being lifted to the surface. A man on the dock saw me trip, and he jumped fully clothed into the water and saved me. Had it not been for him I would not be writing this. I think of the years between that moment and right now. I thought of it again this morning, just before I fed the pigeons. The memory made the feeding more than a chore. It made what was ordinary more than ordinary.

Over the years I’ve thought often and gratefully about another incident that was serendipitous and life-changing. When I finished high school, I had no college scholarship offers, even though I had good grades and was the class valedictorian. One night at a graduation party, a girl I barely knew told me that a certain Dr. Leo O’Donnell, Class of 1917, was offering a scholarship to Notre Dame to a student from Pittsburgh. She told me she could arrange an interview. Within a week I had completed the interview and was awarded the scholarship. Again, this was totally unanticipated and unexpected.

The truth is that Notre Dame literally gave me my life as a writer and teacher. I’ve thought of this often, especially during trying times — like the current pandemic — and a definite peace possesses me. Spiritually I feel above it all. I also think of Rabbi Abraham Heschel’s statement that the ultimate gift of life is to pass from appreciation to gratitude. It’s true.

Many years later I noticed a certain numbness in my hands and feet. I also found myself fighting sleep while driving. One night, totally by chance, I was seated beside a retired doctor at a dinner. He asked me casually how I was feeling, and I mentioned the numbness and drowsiness. He gave me the name of a doctor and said he wanted me to see him the following day — and that he would make the appointment himself. The next day I was diagnosed with pernicious anemia, the inability of the body to absorb vitamin B12. Unless treated by injections of the vitamin on a regular and continuing basis, the situation would worsen, with fatal consequences. I have since administered the injections myself, constantly reminding myself that all of this happened because of a chance meeting with a doctor over dinner — a godsend.

I have heard that everyone has such experiences and that it’s always a matter of luck. While true, it is the kind of luck that has a spiritual dimension, and that dimension becomes more apparent in retrospect. I keep this in mind during times like the present when one hopes one’s luck will hold.

I have lived through times when luck did not hold, and then one can be edified by the unlucky in ways that never fade. Rushed to the hospital after he suffered a heart attack, my father-in-law said these last words to me: “I thank God for everything, and I thank God for this the same.” He died that night, and the memory of it shames me whenever I’m tempted to complain and not make the most of what time remains to me.

I do not recount these different incidents as a pretext for platitudes. Platitudes are for those who look for certitude where there is only mystery. I cite them only to demonstrate that the human imagination is capable of permitting us to be rebels to the end, to refuse to be defeated by what is bent on exterminating us, to see that life still has meaning even in extremis.

In this sense a pandemic can create inconveniences and fear, but the imagination gives us options. Consider the heroism of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Incarcerated in a Gulag labor camp where he was tortured physically and mentally, he managed to keep a record of his imprisonment. He was released after eight years and later spent another 10 years writing The Gulag Archipelago. Published in 1973, the book sold hundreds of millions of copies and exposed the vices of the Stalin era for all the world to see. For this he was exiled, first to Europe and then to the United States, before being permitted to return to Russia, where he died. His life is a classic example of the triumph of the human imagination over suppression and terror.

The Solzhenitsyn story is an extreme example of what man can do to man and how one person transcended it by not letting his imprisonment kill his quest for freedom. Yet numerous crises and catastrophes, which are not political at all, may still present the same challenge to human dignity and freedom — floods, tornadoes, earthquakes, droughts or pandemics. History tells us that invariably after scourges or devastations certain survivors will not only manage to meet their own physical needs but gradually create societies and cultures even better than those that were destroyed. I remember seeing a photograph of a couple in their 80s kneeling upright before what was left of an altar in what was left of a church after the Israeli war on Lebanon in 2006. Thousands of people were killed, every bridge in the country was targeted, tens of thousands of cluster bombs and bomblets littered southern Lebanon, and yet here were two oldsters kneeling in prayer. That image of simple dignity showed the barbarism of war for the waste that it is.

As we weather the pandemic, I’ve discovered that a certain peace can come from following a ritual of one’s choice. It’s what I feel each morning when I feed the pigeons. It’s also the civility that prevails when one dines with one’s family or with others. In our current infatuation with fast food, we mistake feeding for dining. Feeding ourselves on the run prevents breakfast, lunch and dinner from being times of unity through conversation and appreciation. The French correctly contend that dining actuates all the senses simultaneously; we see, smell, taste and touch the food while conversing with those who are dining with us. Among the ironic benefits of lockdowns and confinements are the opportunities they create for families to unite while dining. And if we do that, we manage to keep the depressions and pressures of the pandemic at bay.

One benefit I’ve gained from the pandemic is to read books in a different way. When bookstores shut down, new books were suddenly out of my reach. I began rereading books I had not read in years. As a rereader of Hemingway, I’ve concluded that his later books like Islands in the Stream can’t hold a candle to A Farewell to Arms, although the singular exception may be A Moveable Feast. Rereading about Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg, I learned something about the battle that I did not know and had never thought about; namely, that 5,000 horses were killed there.

When I reread Romeo and Juliet, I found that Friar Laurence’s description of Romeo in love applies to lovers everywhere and always: “A lover may bestride the gossamer that idles in the wanton summer air and yet not fall, so light is vanity.” Similarly, the Nobel recipient and poet Octavio Paz, in what I consider the best book on sexual love, said that love is the final metaphor for sexuality because there is no love without eroticism, and no eroticism without sexuality. “Every love,” Paz concluded, “is eucharistic.” What lover can deny that?

I also rediscovered this anecdote: The distinguished journalist Irvin S. Cobb was showing a guest his library. In awe of Cobb’s collection, the guest finally asked him, “Have you read every one of these?” Cobb answered ambiguously, “Some of them twice.”

Many books proved to be even better the second time around. This experience convinced me that the “newness” of books stands in sharp contrast with qualities that only grow truer and better over the years. Books give one a sense of permanence in a world in flux, and permanence creates perspective.

Sam Hazo is a poet, essayist and novelist who lives in Pittsburgh. His latest novel is If Nobody Calls, I’m Not Home: The Open Letters of Bim Nakely.