The educator Booker T. Washington preached a gospel of work. Born into slavery in 1856, Washington worked from an early age, carrying water to other enslaved laborers on a Virginia tobacco plantation and bringing corn to a mill to be ground. After emancipation and the end of the Civil War, he toiled in the coal mines and salt furnaces of West Virginia. As a teenager, he went to work for a wealthy white woman, Viola Ruffner. His first task was to cut the lawn.

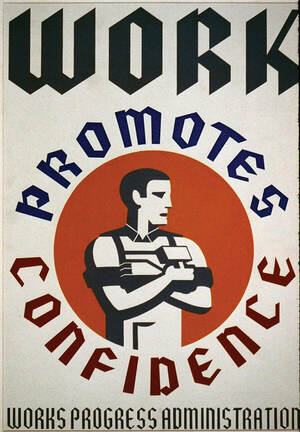

At first, Washington was terrible at it. Struggling on his hands and knees with a small scythe, he mangled the grass. She made him cut it again. “Many times,” he later wrote, “when tired and hot with trying to put this yard in order, I was heartsick and discouraged and almost determined to run away and go home to my mother.” Instead he kept trying and eventually beheld the lawn in its beautiful order. “When I saw and realized that all this was a creation of my own hands, my whole nature began to change. I felt a self-respect, an encouragement, and a satisfaction that I had never before enjoyed or thought possible. Above all else, I had acquired a new confidence in my ability actually to do things and to do them well.”

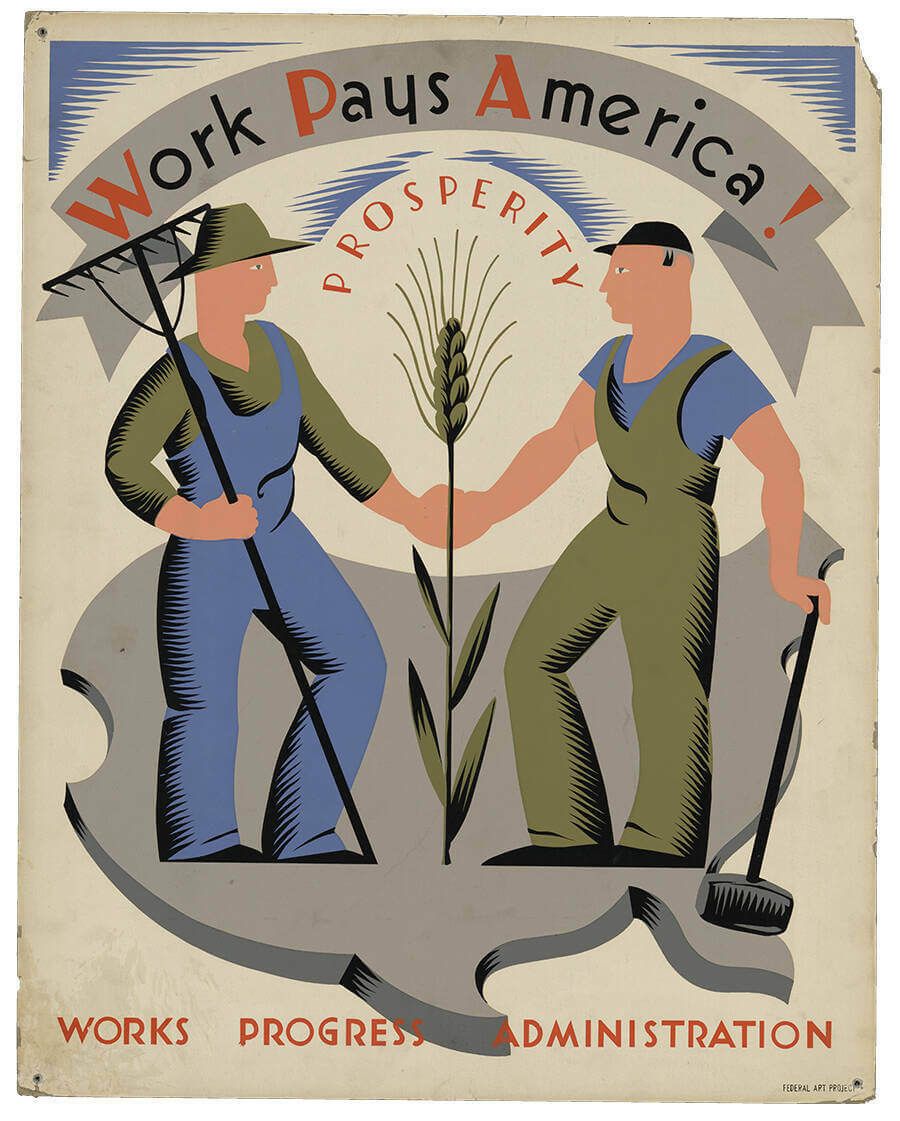

This is not just the ultimate up-by-the-bootstraps story. It is also a perfect distillation of the American belief in the value of accomplishment through work. Your skills may be meager, but your potential for effort is limitless, and if you persist you will see the fruits of your labor. You might point to a chaotic landscape now tamed, an illness cured, steel transformed into a car. Washington’s story contains a moral lesson: Work hard and you will be satisfied, because you will make a visible mark on the world.

This moral seems less true in the fragmented, high-tech world of 21st-century professional labor. Despite Americans’ advanced education and training, we often don’t know what we’re doing at work. The result is chronic alienation and burnout. Indeed, one essential dimension of occupational burnout is a feeling of ineffectiveness, the sense that your work isn’t accomplishing anything. Work is where we expect to be productive, to make a contribution to society. Fortunately, society, even despite the coronavirus pandemic, appears to be functional. But often enough, an office worker can’t quite tell how. And the human cost of this condition is yet untold.

A friend of mine, a history professor, once asked his 6-year-old daughter what she imagined Daddy did at work all day. She paused a moment, then answered, “Type.”

She wasn’t wrong. A huge proportion of a professor’s labor is typing: preparing to teach, grading student work, writing papers, banging out screeds to the dean. The number of professional typists in the United States — about 40,000 today — is diminishing rapidly, but not because there is no typing to do. Indeed, there is more than ever, but the typist’s task has been distributed to virtually every other worker. We all type now, all day long. A 2019 survey by Typing.com found that workers spend most of their working hours typing, an average of 22.3 hours per week. The more they earn, the more they type. Workers who make at least $100,000 per year pass 87 percent of their workweeks tick-tacking on a keyboard.

Much of what we type is email. By one estimate, workers spend more than three hours on work email each weekday, plus another two on personal email. Yet somehow email still feels like a distraction, a constant flashing light in our peripheral vision, always demanding our attention. “Work,” the computer scientist and productivity guru Cal Newport writes, “has become something we do in the small slivers of time that remain amid our Sisyphean skirmishes with our in-boxes.”

In other words, what we do is not what we do.

This contradiction at the heart of human toil is new. Early humans who went through the motions of hunting or gathering would fail the evolutionary test. Most work for the past several millennia has involved producing food and raising children. Both tasks are investments in the future; they require planning and hope. But physical actions and their consequences corresponded more closely in that preindustrial agricultural and domestic labor than they do now in our postindustrial world.

American office workers no longer reap what we sow, because so much of our work occurs in an invisible realm. It isn’t even clear that we are the ones working. We type, and the computer does something, and somehow that keeps the boss off our backs. Our accomplishments are ephemeral. Our products occupy imaginary space in a location we aptly call the “cloud.”

Look at people using their computers: What are they doing? As I write this, I am in a large reading hall in a university library. Most people here have laptops in front of them, as I also do. A dark-haired woman across the room has a laptop and a tablet on her desk. I bet a phone sits nearby, too. She types little, though I can hear her trackpad click every few seconds. She looks intently at her laptop screen, either hunched over to peer in close or else sitting back with her hand to her cheek. I assume she’s a student, but I have no way to tell what her field is. Law? Engineering? Anthropology? Is she analyzing a dance performance or hacking into a bank’s security system? I can’t be sure. What does she study? She studies the screen.

The shift to a typing-based economy happened quickly — too quickly for our cultural understanding of work’s role in a meaningful life to catch up. The Industrial Revolution is only about 10 generations old. Mass electrification occurred barely a century ago in the U.S.: Just as Booker T. Washington was touting the value of human effort, factories began running on alternating current. Office workers today whose careers began in 1980 would remember when typing was chiefly about transferring handwritten notes or dictation into a readable format. When they type now, transcribing notes is the last thing they’re doing.

In the early 1970s, the sociologist Richard Sennett visited a commercial bakery in Boston for his research on social class. He found it a busy, sensual place: “the bakery was filled with noise; the smell of yeast mingled with human sweat in the hot rooms; the bakers’ hands were constantly plunged into flour and water.” The work was difficult and poorly paid. The workers — all men, most of them Greek — did not really enjoy it, but they found meaning in their solidarity with each other. Washington might have pointed to their loaves as evidence of their labor’s merit.

Twenty-five years later, Sennett returned. Everything had changed. The bakers he knew were gone, replaced by men and women of various ethnicities. The process was now computerized. The bakery could churn out everything from bagels to boules, and no one needed to know a single recipe. The machines took care of that. No one broke a sweat in the cool, calm environment. Hands remained clean and dry. One worker told Sennett, “I go home, I really bake bread, I’m a baker. Here, I punch the buttons.” Any pride the bakers once found in the product or process of their work was lost to automation. “Again and again,” Sennett writes, “people said the same thing in different words: I’m not really a baker.”

The bakers’ experience suggests that the crisis in work pertains to an inability to narrate what we do. Alaisdair MacIntyre, a Notre Dame professor emeritus of philosophy, argues in his 1981 book After Virtue that the human being is “essentially a story-telling animal.” Our actions only make sense to us if we can place them within a narrative. “I can only answer the question ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’” Washington situated his labor for Viola Ruffner in multiple stories — not just about his drive to get an education, but also about the way industrious labor would make African Americans equal U.S. citizens. He saturated his work with meaning.

A 2017 study found that physicians in a large Wisconsin hospital system spent nearly six hours per day creating electronic health records, including nearly 90 minutes after hours. They spent most of that time on ‘inbox management,’ a 21st-century form of hacking through thorns and thistles.

The workers at the computerized bakery couldn’t connect their efforts to a bigger story of accomplishment. They didn’t really know what they were doing. Sennett sees this “illegibility” of work to the worker as a key contributor to the “corrosion of character” occurring in technological capitalism. “Character,” Sennett writes, “is expressed by loyalty and mutual commitment, or through the pursuit of long-term goals, or by the practice of delayed gratification for the sake of a future end.”

Developing character, like developing a character in a novel, takes time. You find yourself in a setting, like a Greek enclave in 1970s Boston. In your young life, you have goals and desires, talents and limitations. And you need a job. Your uncle thinks you would fit in at the bakery where he works. The work is hard, he says, but it’s honest. You start the job, and you make countless mistakes. Your co-workers poke fun at you, but they teach you how to bake. In time, you learn skills no one can take away from you.

One day, you’re in the grocery store. You see bread you made that morning on the shelf. You connect the pain in your back, the burns on your arm, to the loaves and the money in your pocket. You feel pride in the work and even in the pain, but you wonder if it’s worth the meager pay. There has to be a better way to make a living, you think. Then you consider your uncle, who got you the job. You can’t be a baker forever, but you can’t let him down, either.

If you’re this baker, your work is legible. It makes sense within the story of your life and community. Your job offers a framework within which you make consequential moral decisions that connect your past and future.

The shift to automation, to illegible and de-skilled labor, calls that into question by prioritizing employee flexibility and risk, the possibility of “disruption.” Such changes detach workers from the character-forming nature of work and make it difficult to place work within the narrative arcs of their lives.

Illegibility may seem like a minor problem compared to the indignities many American workers suffer. The work of a customer service representative at a call center may be legible — they take calls from angry people all day — yet it is often without satisfying results. Meat packing is, if anything, too legible, the process so gruesome as to cause psychic damage to those who do it. And low-wage workers may have needs more practical than a narrative. Still, connecting their experience on the job to a story they can tell might help them organize for better conditions. “I’m being exploited” is a narrative of work’s meaning, too.

The changes Sennett described in the bakery have migrated to seemingly every field. Medicine is now largely a matter of typing. A 2017 study found that physicians in a large Wisconsin hospital system spent nearly six hours per day creating electronic health records, including nearly 90 minutes after hours. They spent most of that time on “inbox management,” a 21st-century form of hacking through thorns and thistles. According to numerous studies, doctors view electronic record keeping as a major stressor, decreasing their satisfaction and leading to burnout. And why wouldn’t it? No one goes into medicine to type.

Just a few decades ago, it would have been easy to see the difference between a baker and a physician. They performed very different physical actions. But if all work is typing, which keystrokes distinguish the baker from the doctor from the accountant? Or the good doctor from the bad one? Of course, the knowledge and skills that distinguish one from the other are real, but they’re often invisible.

Such questions drove the physician Sumner Abraham to a career crisis. Two years ago, Abraham was a head medical resident at a major university hospital in Virginia, with 110 people reporting to him and his three colleagues. The job involved teaching and helping residents handle the cognitive and emotional demands of a career in medicine, but it also involved office work: scheduling, training on electronic records systems, mediating disputes. It was a prestigious job in its own right and a steppingstone to an academic career — he received a dream offer to stay at the university hospital. But questions about the meaning of his work gave him pause.

“I had this ironic moment where I couldn’t make sense of what I had been doing,” Abraham said. Mired in the “busywork” of administration, he had “lost a sense of what it means to practice medicine, what it means to take care of people. . . . That’s when I realized it was a problem.” His upward career path seemed more like a dead end. In response, Abraham turned down the job offer, left the hospital and moved home to Mississippi.

What can we do about what we do? Making our work more legible so we can fit it into meaningful narratives doesn’t mean bosses should give smarmy pep talks, telling the keyboard tappers and mouse clickers in the cubicle farm that they are contributing to world peace by helping people save 50 bucks on a flight to Acapulco. The narratives need to be authentic. They need to come from workers themselves.

Sumner Abraham switched career tracks to something he thought would better reflect the story he’d laid out for his life in his medical school application essay. Leaving academia, he joined a clinic in northern Mississippi that serves a vast rural area with few physicians. The first time he met a new patient, he would spend 45 minutes with them instead of the standard 15. “We’re not talking about what medicines you’re taking, or what specialists you’re going to see,” he said. “It’s, ‘What was it like taking your grandson to the state fair to show a goat?’ or ‘What’s your soybean crop look like this year?’” The point is to hear the patient’s story, to understand one’s life, one’s hopes. Then, together, the patient and Abraham could decide how medicine fits into it.

These conversations occurred without a computer in the room. Abraham said he won’t type while patients talk. “That just doesn’t allow you to be present.” Instead, he takes handwritten notes and enters them into the computer later. Despite his aversion to screens in examining rooms, he believes electronic health records can be useful when they’re used to narrate a life rather than check boxes alongside medical jargon. When Abraham follows up with a patient, his first question might be, “How was your grandchild’s wedding?” Not, “So why are you here?”

When I spoke with Abraham in 2020, he was a few months into his practice and even busier than when he was supervising residents. “But it’s a lot more life-giving, because I’m doing what I set out to do,” he said.

I followed up with Abraham this summer and learned he was about to switch tracks again, so he could try to implement his story-driven vision of medicine on a scale beyond his own practice. He is now associate chief medical officer for Relias, a hospital management and staffing company that aims to improve patient care by helping health care providers flourish. In his own story lies a truth about how medicine ought to be practiced. His career is a quest to follow that truth.

Many people today are trying, like Sumner Abraham, to make their work more like Booker T. Washington’s — to make their accomplishments more visible, so they can place what they do in those bigger, more meaningful narratives.

But for many forms of office work, this ideal is impossible. Some of what we do is just hopelessly abstract — and possibly pointless. I couldn’t even guess what it might mean to be a category management planner or data engagement coordinator — positions advertised on LinkedIn as I write this. But people will do those jobs, and they will want to make sense of what they’re doing. To do so, they may need to embrace the reality that work isn’t always designed to accomplish something tangible. We don’t always get to take pride in a job well done.

I know the good that can come, in the right conditions, from work that has no product. After finishing graduate school, I got a job as a parking lot attendant. My workplace was a small, rough-hewn wooden booth behind a pizza shop. I would open the lot at 8:30 a.m., get coffee and enjoy two hours of solitude before the first customers arrived.

Such work offers a basic living — so long as it’s paid well enough — as well as possible narratives of contemplation or personal growth. I read Kierkegaard in the booth and saw myself reflected in his description of a similar period in his life: “Although I was never lazy, all my activity was nevertheless only like a splendid inactivity.”

It was the best job I’d had to that point. I found little sense of accomplishment in parking-lot work. I didn’t take satisfaction knowing the lot had been well parked, whatever that might mean.

Instead I felt the lack of exhaustion. The job didn’t drain me. It didn’t feel like a pointless struggle toward questionable ends. I got to be myself, to maintain a consistent character across my workday.

Further, I felt solidarity with the other attendants, most of whom were, like me, overeducated young men. They might stop by the booth when not on duty and hang out for a while. We were friends off the job, too. When we got together, conversation often turned to parking: which customers owed us money, how a Chevy Tahoe blocked in a row of cars, what tall tales the dishwasher at the pizzeria told when he dropped by after a shift.

It’s a shame we don’t see many parking lot attendants anymore. They humanize an often-resented transaction. They send you on your way home after a day’s labor. As former attendant John Lindaman says in The Parking Lot Movie, a 2010 documentary about the lot where we both worked, “If 600 times a day you are taking a ticket from somebody, you have 600 opportunities to take a ticket from somebody with your full awareness and to really be present in that action.”

An attendant’s work “is about relationships, not parking cars,” my former boss, Chris Farina, explained over lunch one day, 13 years after I moved on. Some of his customers have been parking there for three decades. The merciless machines that have taken over most parking lots can’t recognize a loyal customer. They can’t give someone they know is struggling a break on their fee. They can’t offer a friendly word at the end of a long day. The machines truly don’t know what they are doing.

Of course, behind every machine, every parking app, lies some form of human labor: someone at a desk somewhere, typing.

Whether or not work is a productive activity, it is always a social relation. Even when you don’t know what you’re doing, you may still find meaning in the stories and relationships the work makes possible.

But what happens when neither accomplishments nor human connection are visible? At the parking lot, I looked customers in the eye when I told them how much they owed, but the ethereal, speculative nature of so much work today makes it hard to forge even such basic connections. Our closest collaborators might be far away, people we contact by email — if at all. Many of us have been working remotely for the better part of two years, linked to our co-workers through a data server that could well be in another country.

The answer might be to go inward and deeper, to spiritualize our work while placing it in a larger, cosmic — if invisible — context. We might model our approach on another form of connecting across distances through an unseen realm: the prayer that vowed religious undertake on others’ behalf.

Prayer is not work in the same way accounting or medicine is. It’s unpaid, for one thing, and you can’t get promoted or fired from it. Still, writing in the sixth century, St. Benedict called monastic prayer “the Work of God.” It is the highest activity in the monastery. And for some Benedictine sisters who have retired from active ministry, prayer is an important responsibility, something they take as seriously as secular people take their jobs.

Sister Lois Wedl, OSB, has been a member of the Monastery of St. Benedict in St. Joseph, Minnesota, since 1949. Retired from her job as an education professor, she coordinates the prayer requests that arrive via the monastery website. The requests come from all over the world, offered on behalf of people suffering illnesses, economic troubles or difficult pregnancies.

Wedl often writes back to offer assurance of the sisters’ prayers. “I never say God is going to answer just the way they ask,” she told me. “God knows best. However, God is going to respond — knowing that he is God, and a loving God.”

Often the sisters pray for people they know, and sometimes they get to see a positive outcome firsthand. Long ago, Wedl’s students prayed that a friend would find a kidney donor; years later, the nun saw the woman’s picture in the newspaper. She was dancing with the donor at her wedding.

Most of the time, though, the sisters do not get the satisfaction of seeing a prayer answered in the way they hoped it would be. And often, the sisters never hear from petitioners again.

Were the sisters wired to expect results and take pride in them, they might be dissatisfied by not knowing the good that prayer does or seeing the people it helps. But the practice of prayer has given the sisters a different way of viewing their activity, and it shows in their character. The women are notable for their patience and hope, their empathy for people they never get to meet.

Uncertainty about concrete results, then, is no impediment to the meaningfulness of the prayer. Sister Cecelia Prokosch, OSB, who spent more than 60 years at St. Benedict’s, now lives in a convent for retired sisters. When we spoke in June, several sisters were gathering every morning to pray the rosary for the end of the pandemic. Whether their efforts are making a difference, she cannot know. But by praying for others’ intentions, Prokosch feels she is exercising an ability that most people do not have. “Maybe we have less fear about addressing God than some people,” she suggested.

Her narrative of prayer reflects the division of labor in society — the idea that we do for others what they cannot do for themselves. Such work forms a web of connections to people around the globe. Each of us is a node within it.

Once, when Wedl checked her email in the middle of the night, a request had come from a woman in England who said she felt abandoned by God. She immediately typed out a reply: “God has not abandoned you. I am praying tonight, and I will let the rest of the sisters know tomorrow.” The woman wrote back the next day, saying she wept knowing she wasn’t alone.

Getting that response “really touched me,” Wedl said. “It was so real.”

Jonathan Malesic’s essays have appeared in America, Commonweal, The New Republic and The New York Times Magazine. His new book, The End of Burnout: Why Work Drains Us and How to Build Better Lives, will be published this winter by the University of California Press.