Rock ’n’ roll biographies generally aren’t much better than the National Enquirer.

You get some growing-up snippets. The rest is about gold records, squabbles with band members or record companies, and romances with women named Britt, Anita or Marianne.

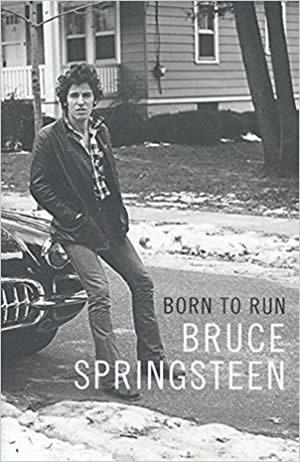

The reason you read is you have hope that you might find a worthy book. You win with Bruce Springsteen’s Born to Run.

I figured I knew Springsteen already, from magazines, TV shows and an overly flattering 1996 book, Glory Days, by Dave Marsh. I knew the catechism — Springsteen’s working-class roots gave him the insights that made him immortal as a rock ’n’ roll musician.

His best songs — including “Thunder Road,” “Born to Run,” “Born in the U.S.A.” and “Darkness on the Edge of Town” — reverberate with disaffection over the runaway American dream. We must leave this place but we will survive, you and me, if we love one another.

Being at the summit of this high hill of singer-songwriters, Springsteen should thank his lucky stars every waking moment. But, of course, we thought that of comedian Robin Williams, who killed himself in 2014, or Kurt Cobain or Ernest Hemingway or Hunter S. Thompson.

We expect our heroes to be happy. It gives us hope because we intend, even with our own meager achievements, to be happy as well.

I wasn’t prepared for the lessons in this Born to Run. This is one of the best-written autobiographies I’ve found. Springsteen says he spent decades writing it, tucking away notes written on scraps of paper. You see in these chapters the same wit, poetry and honesty that you find in his best songs.

It is a joy to read these pages, especially if you’re in Springsteen’s general age group. For example, his description of his first CYO dance in Freehold, New Jersey, could easily pass for the first seventh-grade sock hop in thousands of junior-high gyms in those days before the sexual revolution.

Chaperones armed with flashlights would keep an eye on dancers during slow songs. “They were trying to stop a millennia of sexual hunger, and for that job a flashlight just wasn’t going to cut it. At the end of the night, by the time Paul and Paula’s ‘Hey Paula’ was spun on the decidedly lo-fi gym sound system, every man and woman alike was throwing themselves on the dance floor just to feel a body, almost any body, up against theirs. There in those death-defying clinches lay the promise of things to come.”

Springsteen taught himself to play on a rented guitar, primarily because he saw how feverish women would throw themselves at Elvis and the Beatles. He craved that attention.

He got it but, ultimately, the missing piece from his life was the connection with his father. Like so many men in that era, Douglas Springsteen did not hug or praise. He was sullen and often mean. Beaten down by life, Douglas worked hard jobs and had to be fetched home from dark bars late at night.

By the time he was 30, despite his enormous successes, son Bruce had left a trail of failed relationships. He was known as The Boss but, more accurately, he was a bully, to the women in his life as well as the musicians in his band. His vision of love did not prevent him from selfishness and mistreatment of those close to him.

He became isolated. He lived in dark places, in his words, “out where the buses don’t run.”

Rarely should we care when one of those pampered, lonely-at-the-top celebrities turn sad. Springsteen makes it work. In one scene, he and a pal stop at a Saturday night dance during a road trip at some one-dog town. Springsteen is overcome with sorrow that he’ll never feel love as vividly as those poor souls on the dance floor.

He wants what we have.

I concentrate on it here but the book isn’t totally about Springsteen’s fragile mental state. If you haven’t read already about the inspiration for his songs or the reasons he’s ditched the E Street Band several times, those words are here. It is like other rock ’n’ roll books in that regard.

The real story, though, is in his struggles. He’s been in therapy for decades, wrestling with his doubts and demons. He takes medication that doesn’t always work. After his father and two of his E Street Band members died, he straddled the abyss. “It’s in me, chemically, genetically, whatever you want to call it, and as I’ve said before, I’ve got to watch. The only bulwark against it is love.”

I listen to his music differently now. Whether it’s “Badlands” or “Darkness on the Edge of Town,” I know it’s real and Springsteen has been there.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and a former reporter and editor at the South Bend Tribune.