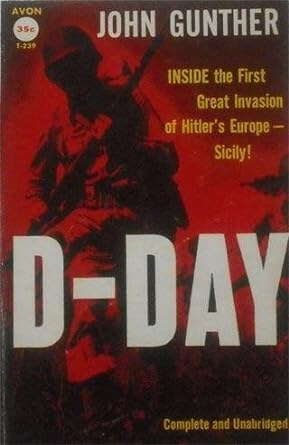

To prepare for an upcoming trip to Normandy under the auspices of Notre Dame’s Alumni Association, I strolled over to Hesburgh Library to peruse books about D-Day. One volume immediately caught my eye.

Titled simply D Day, the author was John Gunther, a highly regarded foreign correspondent from the 1930s until his death in 1970. He wrote a series of popular and probing “insider” books about nearly every part of the world: Inside Europe, Inside Asia, Inside Latin America, Inside Africa and so on. His Inside U.S.A., originally published in 1947, remains an engrossing survey of American life and culture that came out last year in a 75th anniversary edition.

On the third page of D Day, Gunther mentions the date of “June 27, 1943,” and I began to wonder when the book first appeared. A quick internet search revealed the date of publication was March 8, 1944. But didn’t “Operation Overlord,” the code name for the Allied assault of Western Europe during World War II, begin three months later on June 6, 1944?

Gunther’s reference to “D Day” is different from “D-Day,” with its addition of the all-important hyphen between the “D” and “Day.” The military’s generic term, “D Day,” to designate the beginning of any planned action was transformed into “D-Day” by the massive and valorous air, sea and land aggression that took place on the Normandy beaches and their surroundings nearly 80 years ago.

D Day — as opposed to “D-Day” with over two dozen books about that historic date in Hesburgh — focuses on the onslaught by Allied forces of Sicily that began on July 9, 1943, and continued for six weeks. Code-named “Operation Husky,” this offensive was the first one carried out in Europe and preceded the attack on mainland Italy, starting early in September of ’43.

Though Gunther takes readers close to the action — he remarks he was “the third American to set foot on this part of Axis Europe” — the noteworthy sections of his diary-resembling account provide a close-up portrait of General Dwight D. Eisenhower in the months before he was named supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, with responsibility for all aspects of the massive undertaking to free the continent of Nazi occupation, beginning with the blitzkrieg at Normandy.

By then, the overlord of “Overlord” had commanded Allied combat in North Africa during late 1942 as well as the Sicily and Italy campaigns. Still, everyone on both sides of the Atlantic expected General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army chief of staff since 1939 and a future secretary of state and secretary of defense, to be appointed the leader of the military forces going into France and then across Europe.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided otherwise and announced his choice of Eisenhower in a fireside chat on December 24, 1943. FDR had relied on Marshall’s advice for the first two years of the war and didn’t want to lose his counsel in Washington by shipping him abroad.

Readers of D Day during the spring of 1944 learned more about “General Ike’s” style of leadership than they'd previously known. Meeting with a few correspondents, Eisenhower promised to be helpful in providing information for their dispatches, but he made a single, specific, inflexible demand: “nothing whatever about himself personally,” Gunther wrote. “No word at all about Eisenhower, except when mention of the C.-in-C. [commander-in-chief] was essential to the story, and then only in connection with the other high officers of the Allied command.”

This desire for near-anonymity — “to keep in the background” in Gunther’s phrase — and to share the credit extended to firm instructions for filing stories from the field. “He will not allow correspondents to dateline anything as from ‘General Eisenhower’s Headquarters,’” Gunther noted. “He insists on the term ‘Allied Headquarters.’”

Throughout the depiction of the commander, Eisenhower is shown to emphasize collegiality and cooperation among the fighting forces from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and elsewhere as the hallmark of his approach. We’re all in this together is his mantra, with no outfit better than any other for this common cause.

Despite his solidarity with fellow combatants, the resolute general was clear-eyed about his foes, saying in a telling quotation, “You know, I’m not one of those people who find it hard to hate my enemies.”

As Gunther spent more time with Eisenhower, he took his measure with shrewd specificity: his “essential toughness, even ruthlessness,” his “art of human relationships,” his “modesty” and his “complete lack of personal ambition.” The author completes the profile by saying that the general “is quick, bright, realistic, and packed solid with common sense.”

Everything in D Day provides a prelude to the enormous attention Eisenhower received in the months leading up to and after June 6. By reading it, the public had a stronger sense of the officer in command, who incredibly was promoted from a one-star brigadier general in 1941 to a five-star “General of the Army” at the end of 1944.

What’s fascinating about Gunther’s observations of Eisenhower’s administrative style in 1943 is its similarity to how the general conducted himself when he became America’s 34th president a decade later. The seeds of his leadership method, especially his penchant for staying in the background as much as possible, took root with his wartime assignments of command.

The most insightful analysis of Eisenhower’s two White House terms, from 1953 to 1961, is Fred I. Greenstein’s The Hidden-Hand Presidency: Eisenhower as Leader. Through close study of the first Republican administration since 1933, Greenstein explains his subject’s “indirect,” near stealth-like process of governing.

Eisenhower called the shots and made the final decisions but avoided “look-at-me” constant recognition. His style was definitely more hands-on than hands-off, yet it was difficult to detect fingerprints.

D Day is a foreshadowing of “D-Day.” An astute reporter chronicles a critical period before June 6, 1944, and the decisive invasion of Normandy that year. At the time, the Allies were beginning to post their first victories on European soil, and the commander in charge was emerging as the most consequential military figure of the Second World War before he assumed even greater responsibilities in Washington.

Bob Schmuhl is the Walter H. Annenberg-Edmund P. Joyce professor emeritus of American studies and journalism at Notre Dame. He’s the author most recently of The Glory and the Burden: The American Presidency from the New Deal to the Present. His new book — Mr. Churchill in the White House — about Winston Churchill’s meetings with Roosevelt and Eisenhower during the 1940s and '50s will appear in 2024.