My wife hates to hear this, but one of my favorite classes at Notre Dame was a study of bestselling American novels.

While she was slogging through Beowulf and Gilgamesh at Miami University (the Harvard of the Midwest), I was speeding through Peter Benchley’s Jaws and Erich Segal’s Love Story. Our purpose was to ask this question: What is it in our culture that would cause millions of Americans at a time to be drawn to these books?

A vastly simplified answer in most cases? The fear of war.

Benchley’s great white shark might as well have been named Ivan or Igor. Like a Russian spy, he hid in the depths, ready to chew us in half as soon as we let our guard down. Similarly, Segal’s tragic lovers, Oliver and Jenny, gave us all a warm, fuzzy distraction until Jenny was diagnosed with terminal leukemia — similar in effect to a war or a deadly shark.

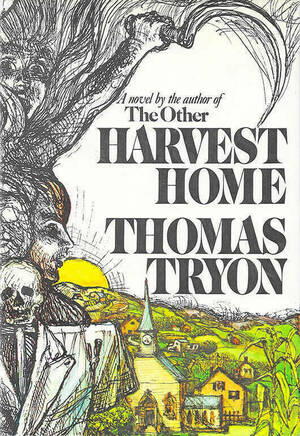

A lesser-known third book we studied was Thomas Tryon’s Harvest Home, which was a New York Times bestseller in 1973 and was made into a television miniseries in 1978.

The basics of the book are these: Ned Constantine, a middle-aged man weary of his advertising job in the big city, moves his wife and daughter to a remote Connecticut village so he can set up a studio and become a painter.

The village, Cornwall Coombe, is wary of outsiders and clings to its 17th-century ways. Its folk plant, tend and harvest corn without the benefit of machines. Festivals celebrate each step of the corn chronology with a Harvest Lord and a Corn Maiden. All of this seems to be controlled by one of the village elders, the Widow Fortune.

Ned starts prying into these traditions as well as the death of a young woman whose gravestone stands alone outside the village cemetery. He is also intrigued by rumors of a howling ghost that keeps villagers from venturing into the forest separating Cornwall Coombe from a nearby town.

Despite warnings, Ned continues his clumsy investigating and learns that something dreadful will happen during Harvest Home, the year’s final ceremony that men are strictly forbidden to attend. And, of course, Ned defies the rules and watches as the rituals go beyond his worst fears.

This sort of horror fiction has become a staple in our culture, particularly in movies. We sit in theaters silently begging the heroes not to open the basement door as they close in on whatever irresistible mystery they are solving.

What drew me back to Harvest Home nearly 50 years later is the deeper message it now delivers about the European-American experience.

Through much of American history, the goal of immigrants and their descendants was to escape the bad things our ancestors once had to survive. We were, as the Statue of Liberty poet proclaimed to the world, “the wretched refuse” of that “teeming shore.” We would escape the wickedness of Old World metropolises and cleanse ourselves in the wilderness of the New World.

And what did we do here? Particularly in New England, we cleared the forests and built villages that grew into towns that grew into cities that grew into new metropolises to rival London and Paris. Our population centers became corrupt, and our literature reflected that. Upton Sinclair’s 1906 bestseller, The Jungle, is the best example.

In the 1950s, we abandoned the inner cities, creating compromise communities in the suburbs. For some, that was the answer. For others, it wasn’t.

A big part of the hippie movement in the 1960s and ’70s was a glorification of natural life. Communes and back-to-earth outposts sprang up so we could escape artificiality. That’s what the Manson family was doing until Charlie ended up in prison.

Tryon’s Cornwall Coombe is an attempt to answer the question: Where do we really belong? This concept here is a colonial village where people live their own lives but come together for the common good, in this case the propagation of corn. When all else fails, one might go back to such roots — to a Cornwall Coombe, if not to the Garden of Eden itself.

But Tryon reminds us that we beelined out of Eden for a reason. We wanted to see the creator’s big picture, but we lacked the capacity to do so. Ultimately, separated from our creator, we have sought to survive in the New World — too often through fanatical devotion to beliefs we think might explain things we can’t understand.

Once upon a time in New England history, our ancestors depended on witches for explanations, and then they burned the witches because they didn’t understand them either.

Harvest Home isn’t about witches as such. It’s about how, wherever we go, we’re likely to find whatever we were trying to leave behind. Or worse. That, to me, is the American experience.

As I recall, Tryon’s book was extremely popular but got the stink eye from the literary elite.

The reason? Tryon wasn’t a serious writer. He was an actor in mediocre movies who hemmed together a bunch of this-and-that for his novels. Harvest Home was a quick read. All the words were spelled right.

I understand. I spent a lot of time and money learning how to discuss the mermaids of T.S. Eliot, the brown study of John Whiteside’s daughter and the revealing alliteration of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ kingfishers. It’s not fair if you get the same insights from a comic book.

Still, Harvest Home somehow hit the mark. Maybe you found yours in the war tales of Beowulf or Gilgamesh. Sorry. That’s someone else’s nightmare.

Ken Bradford is a freelance writer and former reporter and editor at the South Bend Tribune.