If writers were something one drank instead of read, Hemingway would be a shot of whisky and Faulkner the entire bottle. Tom Wolfe? An Electric Kool-Aid dose of LSD. But America’s best literary libations hail from New England. Emily Dickinson leaves a complex aftertaste. The bracing Robert Frost has an icicle swizzle stick. Melville? A stout with a whale-blood chaser.

Most satisfying of all is a tall glass of Maine spring water — easy to swallow, it revives the soul and leaves one more clearheaded than before. This pure, deep, transparent stuff is E.B. White.

Best known as the author of Charlotte’s Web and Stuart Little and as coauthor of that guide to good writing called The Elements of Style, White won a Pulitzer in 1978 for the body of work that included his years as a writer for The New Yorker. He joined its staff in 1927, two years after its launch, and “he brought the steel and the music to the magazine,” according to playwright Marc Connelly.

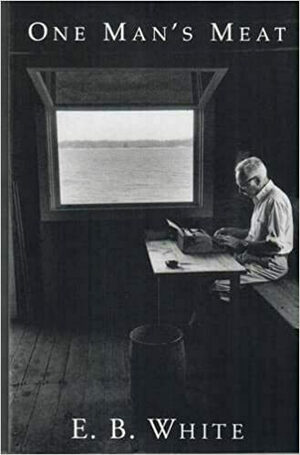

White’s true mettle is best found in his less well-known collection of essays, One Man’s Meat, meditations on farm life and the fate of the world that he wrote for Harper’s between 1938 and 1942.

He and his wife Katharine, The New Yorker’s fiction editor, had fled Manhattan to live full time on their saltwater farm in Brooklin, Maine. The word “fled” is apt. “I smell something that doesn’t smell good” in New York City, he wrote. “There is a decivilizing bug at work.”

His keen nose, decades ahead of other cultural observers’, had become repulsed by the city’s “easy virtue,” a spiritual weakening he felt was caused by technology, mass media and consumerism.

White became a husbandryman, the master of 15 sheep, 148 hens, three geese, a pig and “a captive mouse.” In one year, he hauled in a quarter ton of cod, haddock and mackerel. He harvested everything from oats and hay to apples and asparagus.

He dismissed his own agricultural efforts, calling them “a cheap imitation of the real thing” and said “much of my activity has the quality of a little girl playing house. . . . My demeanor is that of a high school boy in a soft-drink parlor.”

If that’s the case, would that we all sipped from that cup. A well of wisdom, One Man’s Meat succeeds in being many things at once. White’s diary of farm life, his commentary on World War II and his musings on rural America are tributaries of a river that carry the reader on the smoothest of all possible rides.

“The approach to style is by way of plainness, simplicity, orderliness and sincerity,” writes White in The Elements of Style. This is what one finds in One Man’s Meat — the plain, simple, orderly, sincere reflections of a thoughtful, decent man who listens to the war news (“It is a source of relief, after listening to a radio broadcast, to take my .22 and go out to the barn and shoot a rat”), serves as an air-raid warden (“For a few minutes I was brother to Paul Revere”), and gets roped into a midnight coon hunt and notices how “the bare birches wore the stars on their fingers, and the world rolled seductively, a dark symphony of brooding groves and plains.”

Just before the Nazi invasion of France, in his April 1940 essay, “A Shepherd’s Life,” White describes the birth of a lamb (“a little tomato surprise” for the ewe, he calls it) and how the ewe revives its sprawling offspring by cleaning its “forward end” before its “after end.” He sees hope in the coming of spring (“This is a day of high winds and extravagant promises”) and in how geese and lambs share straw beds for their mutual benefit (“Things work out if you leave them alone”). Along the way, like an assassin of the essay’s calm, he slips in the line, “This is a day of the supremacy of warmth over cold, of God over the devil, of peace over war.”

By the last paragraph he seems to mock his own midwifery. Instead he is doing the opposite, while revealing how he captures the attention of his readers: “When I was a novice I used to work hard to make a lamb suck by forcing its mouth to the teat. Now I just tickle it on the base of its tail.”

Anyone wanting to know what it felt like to be an American during the war years will find out in this book. White loved his country, writing in July 1940, “I believe in freedom with the same burning delight, the same faith, the same intense abandon that attended its birth on this continent more than a century and a half ago. I am writing this declaration rapidly, much as though I were shaving to catch a train. Events abroad give a man a feeling of being pressed for time.”

Six months later, he hammered the new book by fascist sympathizer Anne Morrow Lindbergh. “She says: ‘I do feel that it is futile to get into a hopeless “crusade” to save civilization.’ Maybe it is, but I do not think it entirely futile to take up arms to dispossess tyrants, defend popular government, and promote free methods.”

In December 1941, he offered this gem — “To hold America in one’s thoughts is like holding a love letter in one’s hand — it has so special a meaning.”

White sows warnings about the future. “I am fascinated by the anatomy of decline,” he admits. Of TV, he writes, “We shall stand or fall by television — of that I am quite sure.” Reflecting on religion’s waning influence, he observes, “The church merely holds out the remote promise of salvation: the radio tells you if it’s going to rain tomorrow.”

In what could have been a commentary on social media, he predicts that “more hours in every twenty-four will be spent digesting ideas, sounds, images — distant and concocted. . . . We shall be like the insane, to whom the antics of the sane seem the crazy twistings of a grig [a small eel].”

By December 1942 the war had driven government intrusions into daily life. In “Control,” he sees no end to this. “And the reason there will be a couple of strangers in all your barns and offices from now on poking through your piles of accumulated trouble is that somewhere in the past there were those vast untested herds spreading their fevers through the world. This is a sad outlook but one we shall have to face with what cheer is left in us.”

A mid-20th-century Thoreau, White often tapped out his work on a manual typewriter while sitting in a 10-by-15-foot boathouse by the ocean’s edge. He visited Walden Pond in 1939 and addressed the long-gone recluse directly: “As our goods accumulate, but not our well-being, your report of an existence without material adornment takes on a certain awkward credibility.” Perhaps so, but nothing — not one syllable — is awkward about E.B. White’s way with words.

George Spencer is a freelance writer who lives in Hillsborough, North Carolina.