I love a family saga, especially one set in the American West where the characters are as outsized as the mountains and the endless sky. Add in biting ethical questions, and I can’t put it down.

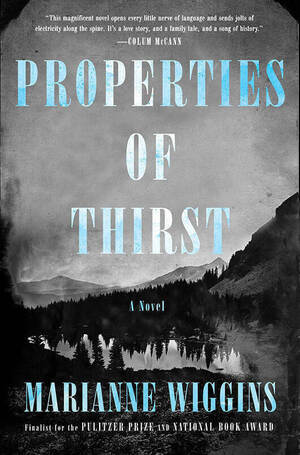

Such was the case with Marianne Wiggins’ new Properties of Thirst, set in the Owens Valley north of Los Angeles in 1942. The patriarch, Rocky Rhodes, renegade son of an East Coast robber baron, has already been battling the L.A. Water Authority for years. The agency, as personified by the uneducated louts careening about in pickup trucks and pointing their rifles at all and sundry, has destroyed the valley and all its inhabitants, human and otherwise.

Most noticeably, the diversion — or theft — of the valley’s water has turned its lake into a desiccated bowl of poisonous dust. The people who’ve managed to hang on to their homes are now plagued by coughing. And the ducks who have rested there for centuries during migration keep returning, though they cannot adapt to the sun-scorched dirt. The senseless deaths of so many birds breaks Rocky’s heart, and the reader’s.

Rocky shares his home with his formidable twin sister, Cas, a musician who gave up her European performance career to care for his twin children when their mother died of the polio virus. Her iron lung still fills their living room. Rocky’s daughter Sunny also lives at the ranch, although she has her own restaurant in town. As a girl she learned French in order to read her mother’s cookbooks. Sunny’s twin brother is listed as missing in action at Pearl Harbor. Despite the family’s personal connections to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, they cannot locate Stryker or his rumored wife and baby.

Into unresolved grief comes Schiff, a Jew from the Chicago tenements. About the same age as Sunny, Schiff worked himself through college and law school to join the civil service as an ardent New Dealer. He’s been named the first administrator of the Manzanar Internment Camp for persons of Japanese descent. The camp, with its barbed wire, tar-paper barracks and clanging flagpole, is right across the highway from the Rhodes family ranch.

Wiggins has put two strong, intelligent, upright men in the position of knowing in their minds and their bones that the laws defining this moment in their lives, and justified as being “for the greater good,” are just plain wrong. Rocky’s nemesis, the law allowing Los Angeles to drain the valley of water for the city’s use, has already created an environmental and social catastrophe. Schiff, a constitutional lawyer, cannot find any defense for the deprivation of the freedom and rights of American citizens, including women and children, that he supervises.

Cas and Sunny, being women in the 1940s, have no overt power in these struggles, but they find ways to subvert injustice. Sunny turns her kitchen into a means by which imprisoned Japanese women can regain their dignity. Cas uses her fortune to legally undermine the unconstitutional actions taken against Japanese citizens.

These four men and women struggle through the impossible contradictions of their situations, each intent on maintaining his or her own honor and obligations to the people they love. Wiggins offers no easy outs or platitudes. Schiff must choose between love and integrity not once but twice. Things catch up with Rocky on a solitary camping trip high in the mountains. By the end, none of the four remain in the valley, though some have found love to console them for their many losses. I cried for these characters. I won’t forget them.

Megan Koreman lives in Royal Oak, Michigan. She is a historian and author of The Expectation of Justice: France, 1944-1946 and The Escape Line: How the Ordinary Heroes of Dutch-Paris Resisted the Nazi Occupation of Western Europe. A young adult novel, Dark Clouds over Paris, is forthcoming. Read more at dutchparisblog.com.