Frank, my brother-in-law, works in the emergency room of a medical center in Arkansas. About twice a year our families get together for the holidays. We catch up on news, share meals and hear how Frank comes to terms with carnage.

Many of Frank’s after-dinner stories involve nail guns, motorcycles, tree branches (“going in and out of him like a fish hook”), astounding extrications, the laughter of doctors, the sheepish confessions of the wounded.

To deal effectively with all the physical damage, a doctor or surgeon has to see it accurately. The job of a radiology technician in the ER is to broaden and sharpen the doctor’s vision. Frank is nearly 50 years old and is very good at this.

Achieving that level of accuracy has taken a toll. Although the flexibility, speed and precision of imaging technology has increased by leaps and bounds, Frank’s work remains physically taxing. The bodies of patients are often very large. Many arrive unconscious. One consequence of handling patients is that Frank has had to undergo back surgery himself.

And things can get weird. Patients walking wounded into an ER are often dazed and confused. If you had shot a steel nail through your jaw, into your brain, and out the other side, you probably would not be in your best mood either — although “Nail Guy,” says Frank, “was totally lucid and kept talking. As he waited, he just daubed the end of the nail with a napkin.” Frank laughs.

Seeing so many wounds in such sharp detail, night after night, year after year — would this not affect how you see the world? If you poke around meat and bones long enough, the whole thing could start to resemble nothing more than a veal chart.

You can see this fascination with the flesh in Frank’s art. When he paints human forms, they are often chimerical — sarcastic combinations of the human and animal. Many of his sculptures look like stylized internal organs, cancerous growths or glazed aortas.

Which brings us to Holy Week.

On Good Friday, we take a long look at physical suffering. In the crucified, we see that God shared it fully. When the whips bit into his back, his skin welted and burned. Pressed thorns scraped his skull. The cross on his shoulders was heavy and rough. When nails were driven, it hurt. And when he was hoisted and had to hang there naked in front of everybody, blood and sweat dripping off his nose, his gaze on Jerusalem must have been filled with anguish as painful as anything we could experience ourselves.

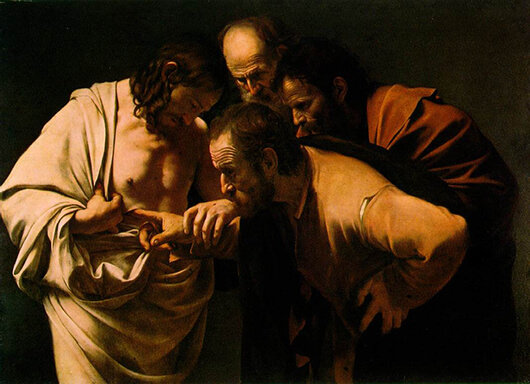

Christian artists have been deeply attentive to Christ’s wounds, but the actual purpose of these wounds in the Gospels is ambiguous. On the one hand, the vividness of detail is an implicit argument against the Nestorian idea that Christ was not a physical being. On the other, the risen Jesus shows his wounds to doubting Thomas so that he may believe — only to praise as “blessed” those who trust without all the poking and probing.

Perhaps there is something to understand about wounds that goes beyond the physical. Even if they do not break the skin, wounds are intrusions from the objective world into our internal life. Even if they scab over, our wounds are subtle reminders that we have been warned. They leave marks (from the Greek, “stigma”) that we carry with us to the end.

Whether we suffer or inflict them, all wounds can be understood as instances of emptiness. They represent the opening of voids. All the jeers or physical degradations we suffer or inflict, all the abandonments and betrayals, are cuts that leave us feeling emptier, poorer, even forsaken.

The fashion today is to take such wounds to therapy, to externalize and confront them, to give them names and see them from all angles. Binding, tending, and coping with wounds are all helpful practices, but do they help us heal damage that goes beyond the physical and emotional?

Leonard Cohen, the Canadian poet and musician whose body regrettably returned to dust late last year, once insisted: “Ring the bells that still can ring / forget your perfect offering / there is a crack in everything / that’s how the light gets in.” These generous lines suggest that our imperfections, our wounds, can be the very openings through which the divine becomes present to us as a power.

And this is what we see in the carnage of Holy Week. To live in the emptiness of our wounds, without covetousness or indifference, is to wait obediently in vigil for the source of all healing. Humbled and opened to the outside, our hearts can turn warm, even solar. Filled with a light that is revelatory, we become impervious to self-deceit or fanaticism:

“Father, forgive them.”

The wounds will surely come. How we see them in the fullest dimension is what matters most.

Anthony Monta is the associate director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies.