- Sisterhood

- Sistering, Sheila Weller

- My Warm Spot, Genevieve Redsten ’22

- Who Do I Say I Am? Maraya Steadman ’89, ’90MBA

- The Ones Who Came Before, Elizabeth Hogan ’99

- A Benevolence of Friends, Mary McGreevy ’89

- Still Some Loose Threads, Maggie Green Cambria ’88

- Flame Launcher, Interview by Tess Gunty ’15

- Rider on the Storm, John Rosengren

- Under the Long Haul, Abby Jorgensen ’16, ’18M.A.

- Writing Her Own Script, Madeline Buckley ’11

- Callings Unanswered, Anna Keating ’06

- Much More than Baby Talk, Adriana Pratt ’12

- Undeterred, Abigail Pesta ’91

- The Good Place, John Nagy ’00M.A.

- Scene Setter, Jason Kelly ’95

- She’s Got Game, Lesley Visser

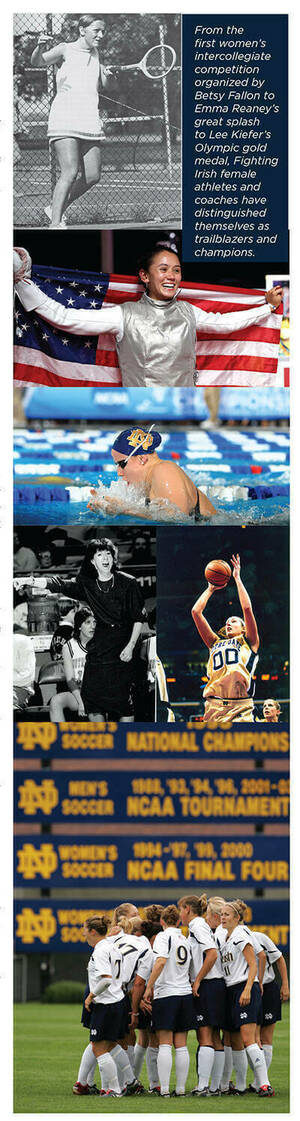

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” Those 37 words, signed into law by President Richard Nixon on June 23, 1972, changed American society. They created the explosion of girls’ and women’s sports that has taken female athletes at Notre Dame and other colleges and universities to national championships, the Olympics and professional careers. The road has not been easy.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 has been challenged many times. In 1974, a bill was introduced to exempt revenue-producing sports from the law’s requirements regarding equal allocation of resources. That amendment was rejected, as were other like-minded proposals in subsequent years. By 1975, federal law specifically prohibited sex discrimination in athletics and gave institutions three years to comply with the new requirements. Attempts to curtail enforcement continued throughout the decade, but in 1980 the brand-new U.S. Department of Education assumed responsibility for overseeing Title IX compliance. The long, hard road to women’s sports equality was being paved with better opportunities.

Under Title IX, every college and university had to demonstrate improvement toward a ratio of male-to-female roster spots equal to its overall student ratio. Women’s sports at Notre Dame and other schools were demanding — and getting — a decent slice of the pie. Young women took to the fields and the courts, the gyms and the pools.

The half-century since has witnessed remarkable progress. This past March, Donna de Varona, the Olympic swimming champion and tireless advocate for women’s sports, spoke at the unveiling of postage stamps commemorating Title IX. Pioneers like de Varona, Billie Jean King and many others fought to implement and preserve the law. Every female athlete today owes her gratitude to the women who overcame those obstacles, both on the court and in the courts.

“Title IX has given women and girls so much opportunity,” says the iconic former Notre Dame basketball coach Muffet McGraw. “When I first coached at Lehigh, my husband and I swept the floor and paid the referees. When I got to Notre Dame, it was still hard, but we had scouting and recruiting. We established credibility — two national titles. Players come to Notre Dame knowing they’ll be ready for the pros.”

The growth in women’s sports has not erased all disparities. “Title IX at 50 is a celebration, but it still demands constant vigilance,” McGraw says, noting a viral TikTok post during March Madness in 2021 that showed “a stark contrast” in weight rooms for men’s and women’s basketball teams at tournament sites.

Like most schools, Notre Dame initially struggled to comply with Title IX. The University began accepting women in 1972, but incorporating women’s sports took many years. Betsy Fallon ’76 organized the school’s first intercollegiate women’s tennis match when she was a freshman in 1973, at a time when female athletes started their own clubs, drove the vans and did the laundry, all for love of the game. In the 1970s, female athletes at Notre Dame dressed in secondhand uniforms, fought for practice time and often arranged matches on their own.

Swimming became a varsity sport in 1981. The next year, three swimmers were All-America selections, including Teri Schindler ’83, who competed in breaststroke at the national swimming and diving championships. Schindler, who became the first woman to produce basketball games for the Big East, was hired by NBA commissioner David Stern to be the inaugural vice president of WNBA broadcasting. She remembers the value of swimming at Notre Dame.

“The men swam before dinner, but our practices were scheduled during dining hall hours,” says Schindler, the co-founder and CEO of a worldwide marketing and technology firm. “I remember so many nights running across the quad from the Rock, wet hair in icicles, grabbing whatever food was left with five minutes to eat. In the mornings, we’d grab a ride on a snowplow to get to the early practices. We were determined to make the program succeed.”

Notre Dame delivered on that promise. After 23 NCAA tournament appearances and multiple Big East championships, the Irish moved to the ACC, where coach Brian Barnes guided Notre Dame’s first national champion, Emma Reaney ’15. Reaney, the most highly decorated swimmer — male or female — ever to compete for Notre Dame, won the 2014 NCAA 200-yard breaststroke in a then-American-record time of 2:04:06.

“I loved swimming at Notre Dame,” says Reaney, who grew up in Lawrence, Kansas. “I had a list of what I wanted — good academics, on a coast, and a combined men’s and women’s program. The first call I got was from Brian Barnes, who’d coached me in Kansas when I was little. I took a recruiting trip to South Bend. It wasn’t on the coast, and it didn’t have a combined program, but something told me I needed to be there. When I went home to Lawrence, I swear, I turned on the TV and Rudy was on the movie channel. I called Brian and said, ‘I’m coming to Notre Dame!’”

In the past 50 years, leveraging its reputation for academic excellence to recruit elite female athletes, the Irish have won national championships in soccer and basketball and fielded top-10 teams in volleyball and tennis. Cross-country runner Molly Seidel ’16 finished her career with four national championships and won a bronze medal in the marathon at last year’s Tokyo Olympics. Softball and golf earned varsity status in 1988, followed by rowing in 1996 and lacrosse in 1997. There are now 13 varsity sports for women at Notre Dame.

But we pause to talk about fencing.

If you’re only acquainted with fencing from The Princess Bride (Mandy Patinkin practiced intensely with famed Olympic coach Henry Harutunian to play Inigo Montoya), then you should know about the female fencers of Notre Dame. The men’s and women’s combined team has won 12 national championships — one more than the football team — and the women have compiled glittering resumes.

Alicja Kryczalo ’05 won 91 percent of her foil matches and was the first Notre Dame student-athlete to become a three-time national champion since distance runner Greg Rice ’39. But is she the best Notre Dame female athlete ever? The Gdansk, Poland, native has serious competition for that title, even from within her own sport.

Mariel Zagunis won Olympic gold medals in individual sabre in 2004 in Athens — becoming the first American fencer to win gold in 100 years — and again in Beijing in 2008. In 2012, Zagunis was selected to be the flag-bearer for the U.S. team in the opening ceremony of the London Games. And in no small irony, in 2017 she competed in the Food Network cooking show Chopped.

Lee Kiefer ’17, another legendary foil competitor, won four straight NCAA individual championships and led Notre Dame to its ninth NCAA team championship. During her senior year, Kiefer became the No. 1 women’s foil fencer in the world — the first American to hold that honor. She made history at the 2020 Tokyo Games, becoming the first U.S. man or woman to win a foil gold medal.

Her father, Steven Kiefer, a former fencing team captain at Duke, was thrilled when she chose Notre Dame.

“Notre Dame has always had a great fencing tradition,” he says while watching his daughter compete toward a first-place finish at the individual foil World Cup in Germany this past April. “They’ve always made the commitment — in facilities, in coaching, in recruiting.”

Kiefer says his daughter took an interest in fencing from an early age. Three times a week he drove her 90 minutes each way from Lexington, Kentucky, to Louisville, for lessons.

“It’s a difficult sport,” he says. “It demands both mental and physical strength, along with precision and strategy. If you’ll notice, the thigh on a fencer’s lead leg is much bigger than the other leg, and one shoulder droops. Lee has cross-trained for years to try and avoid injury.”

Should she become injured, she’ll have ready access to information. Lee Kiefer is in her third year at the University of Kentucky medical school while juggling a demanding athletic schedule. In having such success, she has added to the lore of Irish fencing, which is no less a dynasty than Wake Forest golf or Iowa wrestling.

Women’s soccer at Notre Dame has made 27 NCAA Tournament appearances over the past 29 years and won three championships — 1995, 2004 and 2010 — with runner-up finishes in 1994, 1996, 1999, 2006 and 2008. The Irish are one of only five colleges in the country with multiple national titles, along with Stanford, Florida State, Santa Clara and legendary North Carolina.

Shannon Boxx ’99, a former Irish midfielder, has enjoyed one of the most remarkable careers in women’s soccer history. A four-sport athlete from Fontana, California, and a Parade All-American in soccer, Boxx helped the Fighting Irish to its first NCAA championship in 1995, breaking North Carolina’s nine-year run at the top.

“Notre Dame was my first recruiting visit,” she says, “and after that, it didn’t matter where I went to look. I was going to Notre Dame. College was the first time I represented something bigger than myself. I was representing my school and my teammates. That carried me my entire career.”

After playing professionally for almost five years without making the U.S. National Team, Boxx thought she was happily headed for a career in coaching. But in 2003, at age 26, she became the first “uncapped” player — one without previous national team experience — to make a World Cup squad. After three Olympic gold medals — in 2004, 2008 and 2012 — she added a World Cup victory in 2015, which came with the first ticker-tape parade for a women’s team in the history of New York’s Canyon of Heroes, where athletic champions — along with astronauts, soldiers and politicians — have been honored over the years.

“I owe so much to Notre Dame for making me the ultimate team player,” says Boxx, who was inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame in January.

Boxx’s greatest challenge wasn’t soccer. She’s battled two autoimmune diseases for more than 15 years. Sjögren’s syndrome causes dryness, joint pain and prolonged fatigue, and lupus has added sudden flares of intense pain to her skin, joints and internal organs. An advocate for the Lupus Foundation of America, she played in the Olympics and the World Cup while managing the illnesses.

“I wouldn’t have traded any of my experiences,” she says. “I have so much to be thankful for, and it began at Notre Dame.”

Basketball now carries the school’s mantle of excellence and visibility, but it took a while to run the weave. The varsity team, which launched in 1977, didn’t play a Division I schedule until 1980, which included a 124-48 loss to South Carolina. The program first joined the North Star Conference, then the Midwestern Collegiate Conference.

On May 18, 1987, athletic director Gene Corrigan announced the hiring of coach Muffet McGraw. She retired 33 years later after leading the Irish to nine Final Fours, two national titles and the status of game changer. In every Hall of Fame that has a hoop — including the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame — McGraw’s been celebrated for her coaching, her straightforwardness and her ability to develop players who’ve gone on to success in the WNBA.

Raised in West Chester, Pennsylvania, Ann “Muffet” O’Brien was one of eight children. She grew up playing basketball with the boys at Everhart Park, her shots rattling through the chain nets. Fearless, she was a guard for Bishop Shanahan High School in the early 1970s. If a teammate wasn’t looking for a pass, she’d just hit her in the head with the ball. She says so now with a laugh, but it’s hard to know if she’s kidding.

“I was never afraid, and I wanted to get better,” McGraw says. “Catholic schools were way ahead of the rest of the country, and we had the benefit of watching Big 5 basketball in Philly.”

McGraw attended St. Joseph’s University, 20 miles east of where she grew up. There were no scholarships, but she played point guard for the great Theresa Grentz and later coached there under Jim Foster after playing professionally for one year. Muffet married Matt McGraw in 1977, and he laughed when she wore basketball sneakers to the reception. After five years as the head coach at Lehigh — where McGraw coached Cathy Engelbert, who would become the WNBA commissioner — it was on to Notre Dame.

Women’s basketball in South Bend was struggling for recognition. In 1989, with only 250 people attending the games, athletic director Dick Rosenthal ’54 and assistant director Bill Scholl ’79 came up with a plan. They would market Notre Dame women’s basketball to senior citizens and families with children.

“Those were two groups who were looking for things to do,” says Scholl, now Marquette’s athletic director. “We gave tickets away at the grocery store, the car wash, the Girl Scouts and even the Boy Scouts.”

McGraw made appearances at Rotary Clubs, the Knights of Columbus, schools and churches. Postgame social events gave fans the chance to meet the players. By 1997, when the team went to its first Final Four, the buzz was real. The Monogram Room was too crowded for all the people who wanted to stop in after the final home game against Georgetown. By 2000, the women were averaging 6,500 fans a game.

In 1997, the eye of the tiger arrived with a name: Ruth Riley ’01, ’16MBA. The 6-foot-5 force grew up in a small Indiana farming community loving the movie Hoosiers and recreating the scene where Ollie wins a game at the free throw line. In Notre Dame’s national championship win, with 5.8 seconds left and the score tied, Riley hit two free throws (although not underhand like Ollie) to help bring home Notre Dame’s first title, a 68-66 victory over Purdue. On the podium, Riley pulled on a freshly minted “Notre Dame 2001 National Champion” T-shirt and lit up the arena. Young girls began putting posters of Riley on the wall; young boys lined up for her autograph.

Riley went on to win an Olympic gold medal and two WNBA titles with the Detroit Shock. She was enshrined in the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame in 2019 and serves as a broadcast analyst for the NBA’s Miami Heat.

Niele Ivey ’00, the Irish point guard and captain in 2001, gave a fiery halftime speech when Notre Dame trailed Purdue in that title game, which was played in St. Louis, her hometown. In 2022, as head coach, Ivey had the exquisite challenge of leading Notre Dame into the Sweet 16 while also traveling to see her son, Jaden, power Purdue to the Sweet 16 in the men’s tournament. And Notre Dame’s Olivia Miles became the first freshman — male or female — ever to record a triple-double in an NCAA tournament game.

A decade ago, the hitmaker was Skylar Diggins-Smith ’13. She became the only Notre Dame basketball player in history to compile 2,000 points, 500 rebounds, 500 assists and 300 steals. A WNBA veteran and an Olympic champion, Diggins-Smith has been a marketable star, posing for publications like Vogue and translating her basketball expertise into television work covering the NBA’s Phoenix Suns.

In 2018, America came to know Arike Ogunbowale ’19, she of the inconceivable game-winning three-pointer in the championship showdown against Mississippi State. Some consider it only her second greatest shot of the weekend — after her identical heroics in the semifinal against unbeaten Connecticut. In that game, McGraw called timeout with one possession left and the score tied in overtime. She saw that Ogunbowale was angry that the Irish had blown a 5-point lead and decided to set up the play for her. The guard took the ball at half court, moved to the right wing just inside the three-point line and let it fly. Her step back with one second left gave the Irish a monumental 91-89 win over a team that had beaten them seven straight times, including twice in NCAA championship games.

Ogunbowale, one of nine Notre Dame players now in the WNBA, had her buzzer-beater in the 61-58 win over Mississippi State memorialized in a Buick commercial.

McGraw is mindful of how far women at Notre Dame have come — and the work it took to get them there. In 2012, she had her first all-female staff. She often asked her players what they thought the word “feminist” meant, and most of them explained that it was, ultimately, about opportunity — the very definition of Title IX.

So how influential, how meaningful, has Notre Dame been for female athletes? The question doesn’t surprise her, but she still has to collect her thoughts.

“I always struggle to find the perfect words to say how great Notre Dame is,” McGraw says. “I’m big on accountability. I demanded it from my players and myself. At Notre Dame, everybody makes a promise to do it the right way.”

Lesley Visser is a pioneering sportswriter and sportscaster who was the first woman enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame. She is in her 35th year at CBS.