Editor’s note: In commemoration of the anniversary of the death of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, on February 26, 2015, Notre Dame Magazine is publishing selections from our Hesburgh Special Edition here at magazine.nd.edu. We will publish one piece per weekday through Wednesday, March 2. Print copies of the special edition are available; please visit our store for ordering information.

Tomorrow: The Strength of Leadership, by Anthony DePalma.

In my 34 years at Notre Dame, I walked west behind the Main Building many times and often thought there ought to be a plaque set somewhere in the paving blocks. It would mark the spot where the president of the University turned to his 35-year-old confrere in the Congregation of Holy Cross as both emerged from the crypt beneath Sacred Heart Church. It was June 1952, before the days of search committees and inaugurations, and Father John Cavanaugh, CSC, unceremoniously handed over his office keys to the younger man.

That low-key exchange launched Theodore Martin Hesburgh on one of the most remarkable careers in American higher education.

This happened very near the spot where, three years earlier on his way to the crypt for customary assignments within the religious community, Ted Hesburgh had first been told he would become second-in-command at the University to which he had returned with a doctorate in theology from the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., in 1945. That came as a shock, but the presidency did not.

Cavanaugh’s tenure, which had set Notre Dame on the academic path of becoming a true university, would end in 1952 because that was the canon-law limit to his coterminous office of religious superior. And virtually everyone figured Cavanaugh had picked his successor when he reshuffled the administration in 1949 and put Hesburgh in a newly created position of executive vice president “in charge of the other vice presidents.”

Hesburgh’s years under Cavanaugh’s tutelage were a valuable introduction into multitasking, a skill that would serve him well in future years. “Cavanaugh gave me more to do than seemingly I could accomplish, and when I got it done and went up in his estimation, he gave me more,” Hesburgh recalled. He had to write job descriptions for the new administrative configuration, cultivate donors and oversee the construction of new buildings.

He also had to bring some oversight to the satrapy of athletics. His skirmishes as executive vice president with football coach Frank Leahy (1941-43 and 1946-53) colored his lifelong relationship with intercollegiate athletics, although he did Leahy a great favor by convincing him to retire before his health failed.

Still, Hesburgh’s desire for institutional excellence was writ large and covered sports. He savored victory and could be seen conducting the band after the improbable Cotton Bowl victory in 1979. He did, however, recognize how easily the tail could come to wag the dog, especially at a place where the income from the Rockne years (1918-30) had been historically crucial to campus development, and football in general had been a key to national recognition.

He winced when, shortly after being chosen as president, he was at a West Coast news conference attended only by sportswriters and was asked to assume the hiking position for a photo opportunity. Privately, he vowed then and there to banish Notre Dame’s reputation as a “football school.”

- More from the Father Hesburgh Special Edition

- The Strength of Leadership

- The Endless Conversation

- The Long Twilight

- The Right Side of the Road

The proof that he did so came when the national media trooped through the campus doing his retirement story in 1987. Not one was a sportswriter, and the questions were far afield from athletics — civil and human rights, higher education, the Catholic Church, nuclear proliferation and immigration reform among them. His work on the Knight Commission to reform intercollegiate athletics in retirement continued to reflect an ingrained skepticism about the ability of universities to keep athletics in perspective.

The university Hesburgh inherited in 1952 was succinctly described by him in a report to the Ford Foundation that led to the most important grant in the University’s history, $6 million “to establish regional centers of academic excellence.”

“Our student body had doubled, our facilities were inadequate, our faculty quite ordinary for the most part, our deans and department heads complacent, our graduates loyal and true in heart but often lacking in intellectual curiosity, our academic programs largely encrusted with accretions of decades, our graduate school an infant, our administration much in need of reorganization, our fundraising organization nonexistent, and our football team national champions,” he wrote.

A backhanded compliment by former University of Chicago Chancellor Robert M. Hutchins made the same point. “The Notre Dame efflorescence,” he said of the Hesburgh era, “has been one of the most spectacular developments in higher education in the last 25 years. I suspect that Notre Dame has done more than any other institution in this period because there was more to do.”

While Hesburgh would attack Notre Dame deficiencies one-by-one, what he brought to the task was more important — visionary leadership. “The very essence of leadership is that you have a vision,” he once noted. “It’s got to be a vision you articulate clearly and forcefully on every occasion. You can’t blow an uncertain trumpet.”

Time and time again, he placed Notre Dame in a succession of Catholic universities that had preserved since medieval times the oldest intellectual tradition in the West. He predicted with confidence that Notre Dame could enter the front rank of American universities by melding again faith and reason, belief and learning, moral values and scientific fact.

Philip Gleason, professor emeritus of history and an expert in the history of Catholic higher education, put it this way, “Hesburgh had a high level of what I would call ‘executive intelligence,’ a mind, temperament and intelligence oriented to action rather than contemplation. The times were suited for active leadership, moving ahead, seizing the main chance, and he had the qualities that fit the circumstances.”

Hesburgh moved quickly on the academic front. He appointed new deans in Law (actually done by Cavanaugh but with Hesburgh’s fingerprints on it), Business, Arts and Letters, Engineering, Science and the Graduate School. He looked for men with high academic standards.

“You’ve been running a night law school in the daytime,” was the acerbic evaluation of the new dean of law, Joseph O’Meara. Hesburgh himself described Business as “a yacht club,” drawing an objection from Father Edmund Joyce, CSC, a 1937 alumnus of the college. The dean fired in Arts and Letters was Cavanaugh’s brother, and Hesburgh’s mentor had approved the action.

The upgrading of the faculty was a painful exercise in winnowing the wheat from the chaff, the teacher-scholars of promise from those with “one year’s experience repeated over and over again.” With some exceptions (Frank O’Malley being one), merit increases went to those hired after 1949. Today, one could count on age-discrimination lawsuits flowing from such an action.

He made decisions quickly and seldom looked back. He knew a certain number among his many decisions would be faulty, but he also knew little was to be gained by living out of the rearview mirror.

Notre Dame’s new president also asked for the resignations of all residence hall rectors and then reappointed those he wanted. “I felt many older rectors thought students were there for their convenience,” he explained later. Yet, despite his own chafing at French boarding school restrictions when a rector, Hesburgh moved much more slowly in reforming overall student affairs policies, perhaps because he continued to believe in the essence of in loco parentis and because he also hoped increased academic standards would result in a more mature student body, one more interested in the Peace Corps than in panty raids.

Starting in l961, the restrictive environment began to be loosened. Lights went on all night in dorms, and Mass morning-checks ended, as did patrols of South Bend’s off-limits areas. In spring 1963, students who wanted further changes suggested that Hesburgh step down as president and instead create and occupy the less powerful post of chancellor. They got a letter reminding them that the administration did not consider them “equal partners in the educative process.”

This “Winter of our Discontent” letter might have been a low point in Hesburgh’s relationship with students; it was not long afterward that he argued for student input on various University committees. However, his adroitness in dealing with students was put to the test in the Great Days of Student Unrest, which drew its fuel from opposition to the Vietnam War.

In that rough period for college and university presidents, Hesburgh’s standard joke concerned the university president who died and went to hell. “The only problem was he was there for four days before he realized the difference,” he quipped. On a serious note, he kept what might be called an “academic martyrology,” a handwritten list of college or university presidents he knew who were forced out of office in this turbulent time.

Disturbances at Notre Dame were relatively mild when compared with other campuses, yet they were unprecedented in terms of campus history. An example was the infamous “moratorium Mass,” in which students turned in their draft cards during the liturgy. Standing in the congregation was Hesburgh, who had declined an invitation to concelebrate. His presence on the scene was part of what might be called a Woody Allen strategy. It was Allen who noted that “80 percent of success is showing up.”

Another crucial time when Hesburgh showed up was to speak at a giant protest rally in the main quadrangle in 1970. Student organizers later admitted they asked him to speak first to set him up, only to see him deliver a moving speech asking the government to redress many of their grievances. Students later carried copies of that speech door-to-door, garnering some 20,000 signatures for Hesburgh to forward to President Richard Nixon. On another occasion, he came up with immediate funding for a Program in Non-Violence that provided an academic home for protesters in the Gandhi tradition. He managed to keep one step ahead of students.

To Hesburgh, protest was a matter of manner. One was not free to protest beyond the point where it impeded the freedom of other members of the campus community. You could legitimately picket campus job interviews by the CIA or the Dow Chemical Company, but you could not force fellow students to walk on bodies to exercise their right of access. Students who crossed that line had to accept the consequences.

That was the basis of his famous “15 Minutes or Out” statement in 1969, which came out at the height of nationwide campus disturbances: “Anyone or any group that substitutes force for rational persuasion, be it violent or non-violent, will be given 15 minutes of meditation to cease and desist. . . . If they do not within that time period cease and desist, they will be asked for their identity cards. Those who produce these will be suspended from this community as not understanding what this community is. Those who do not have or will not produce identity cards will be assumed not to be members of the community and will be charged with trespassing and disturbing the peace on private property and treated accordingly by the law.” The ND Archives holds an entire box of news clippings related to the statement, including some 300 mostly laudatory editorials.

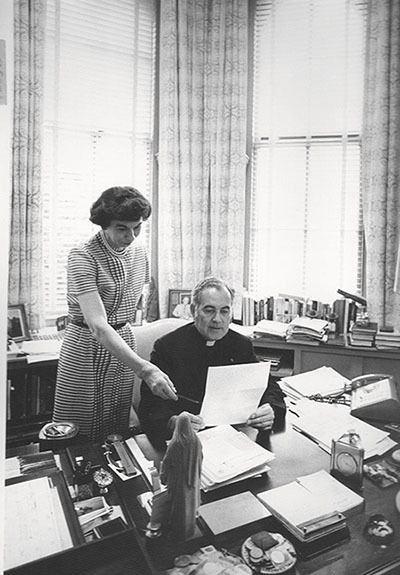

The statement, issued with the endorsement of several campus groups (but not the Arts and Letters College Council) hit a national nerve. There is a famous photograph of Hesburgh’s secretary, Helen Hosinski, framed by some of the 1,000 letters and telegrams received in its wake. It was welcomed by many college and university presidents as a timely defense of the besieged forum of academe but belittled by others who claimed it could only work at a homogenous and relatively conservative Notre Dame. Commonweal, normally a friendly publication, called it “delusionary.”

To Hesburgh’s discomfort, the Far Right made him a folk hero. That persona proved useful, however, when Notre Dame’s president had to intervene with Vice President Spiro Agnew to prevent federal troops being sent to pacify college and university quadrangles. Some years later, Hesburgh pronounced the statement a risky but nonetheless necessary use of the bully pulpit, one that had a positive effect at Notre Dame and in the country.

George Shuster, Class of 1915, 1920M.A., one of Hesburgh’s chief confidants, once remarked that “a president not worth seeing outside is not worth seeing inside.” Beginning with an appointment to the National Science Board in 1954 (Eisenhower wanted a theologian to rub elbows with its members), Hesburgh served an unprecedented (for a university president) 16 presidential appointments. He was also much in demand for higher education commissions and committees, boasting that by 1960 he knew personally every president of a significant American university.

He only took on outside activities that had a moral overtone — civil rights, immigration reform, abolition of nuclear weapons, amnesty for Vietnam offenders, Third and Fourth World development, to name only a few. He was energized by his outside commitments, not enervated. “Unless you do outside things, you run out of gas,” he said. “And I only do things where I think I can bring some fruit back to the place.”

Hesburgh was the public face of Notre Dame, and the University benefited much from its leader serving in such capacities as chair of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. There was occasional irony. While its president developed a reputation for being “the conscience of a nation” in terms of civil rights, Notre Dame’s advances in student and faculty diversity were not dramatic, despite constant Hesburgh prodding.

In some ways, Notre Dame was a university trying to keep up with its president. In polls conducted by a national news magazine to determine the most influential individuals in several fields, Hesburgh during the last half of his presidency was invariably among the top three in both education and religion. This was before Notre Dame itself made the Top 20 list for undergraduate education among national universities.

In his off-campus ventures, Hesburgh was often the first priest in a particular position. He was the first priest to serve on the board of the Rockefeller Foundation, the first to serve in a formal diplomatic capacity for the United States, the first to be elected to the Harvard Board of Overseers. In these capacities, the Roman collar was an advantage, bringing with it a certain amount of moral suasion. In fact, he had more influence in secular matters than in church affairs.

Because he was never a member of the hierarchy, he did not have the clout of, say, a Cardinal Joseph Bernardin. Not being a bishop, however, allowed him to have his extensive secular portfolio. He turned down opportunities to join the hierarchy. He could have been an auxiliary bishop in charge of military chaplaincy or bishop-head of Catholic Relief Services. Pope Paul VI, with whom he was particularly close, once gave him “a cardinal’s ring,” which he stashed in his desk drawer. On the secular side, President Lyndon Johnson wanted him to head the space effort, and Nixon asked him if were interested in taking over the poverty program. Both got a no.

His outside commitments were abetted by two people: his colleague, Father Joyce, and his manager, Helen Hosinski. Joyce was the ideal No. 2 — competent and completely loyal. Until the appointment of a provost, he ran the University when Hesburgh was on the road, and the president seldom made a phone call back to campus or had correspondence forwarded. The two priests complemented one another — a Yankee and a Southerner, a spender and an accountant, a moderate and a conservative.

Joyce wielded considerable campus power even after the appointment of a provost as second in executive authority. He was in charge of the budget, and if you followed the money it always led to his office. Joyce was like a brother to Hesburgh. “When Ned died [in 2004],” said Hesburgh, “I felt it here [gesturing to his heart], and it took me six months to really recover.”

Helen Hosinski did everything from telling Notre Dame’s president when to get a haircut to sending out his 2,800 Christmas cards. She could expertly forge her boss’s signature but would not do so on memorabilia, such as a photograph (“They deserve the real thing”). She would, however, easily sign Hesburgh’s name to a federal grant form, technically a felony. With arthritic fingers and an electric typewriter, she slew correspondence and piled it up on the windowsill behind Hesburgh’s desk. She was a gatekeeper extraordinaire who invariably lied about when Hesburgh would be returning from off-campus trips in order to give him a breather. He worked the dark side of the clock, and she left at 5 p.m. no matter what.

“Helen knew virtually everything I did, but she was an absolute sphinx when it came to information,” Hesburgh recalled. “I never had a leak from the office.” (Those of us in public relations agreed — if there was a leak from the president’s office, the culprit was always Hesburgh himself.) Helen died in a nursing home in 2000.

As an administrator, Hesburgh had just a few maxims. He did not want two people worrying about the same thing, and he did not like handling the same piece of paper twice. He allowed his subordinates considerable latitude in decision-making and expected them to bounce things to his busy desk only by way of exception. He made decisions quickly and seldom looked back. He knew a certain number among his many decisions would be faulty, but he also knew little was to be gained by living out of the rearview mirror. He chaired the Academic Council, and nothing passed that group of faculty and administrators that he opposed.

He was careful not to inhale praise; he knew he would always be No. 00652 to the people who worked in the laundry.

He was marvelous with the media. He respected their role but knew enough not to say anything to a reporter that he was not prepared to read in The New York Times the next day. With his outside activities often generating sparks and campus issues continually cropping up, we occasionally had to clear the decks of interview requests by having “bring-your-own-questions” news conferences. We would supply him with a list of likely questions covering a variety of topics; the answers were always his own. He also could duck a question well. A Time magazine writer once asked him, “Do you believe birth control is a sin?” His reply: “I hope not. I have been practicing it all my life.”

He was treated well by the national press over his lifetime. He was featured on CBS’s 60 Minutes, as well as that network’s short-lived program Who’s Who. He was profiled in virtually every major-market newspaper and national magazine at one time or another. Time featured him on its cover in 1962, and the story was one of five the magazine devoted to him during the years of his presidency.

As for his own preferences, he read only The New York Times regularly. Once asked why, he succinctly explained, “I read things there I do not read anywhere else.” When abroad, he relied heavily on the BBC radio news, although his facility in French, Italian, German and Spanish meant he was not dependent on the International Herald Tribune for printed news. His most embarrassing appearance in print was when Penthouse magazine lifted one of his commencement addresses and promoted it in its inaugural edition of September 1969 as though it were a submitted article. We got letters.

Commencements were familiar sites for Hesburgh. He was cited in the Guinness Book of World Records for having received the most honorary degrees — 150. Some thought it unseemly to count, but I think he welcomed the honors as peer recognition.

The King of Thailand once appeared to be closing in on Hesburgh’s honorary degree record, and he was deeply skeptical, there not being a lot of universities in his majesty’s area of the world. I sent a list of Hesburgh’s honorary degrees to the Thailand embassy in Washington, praising the King’s honors and asking to see their provenance. We never heard back from the embassy, and the King faded as a competitor. Hesburgh’s addresses at graduation exercises were an example of changing the audience rather than the speech; they were adept examples of “mix-and-match.”

The one place Hesburgh relaxed was at the Notre Dame properties near Land O’Lakes on the border of Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He had purchase on a small cabin on Tenderfoot Lake and sometimes grew a Hemingway beard. He read late into the quiet night, listening to the loons and classical music on public radio. In the day, he fished muskie, northern and walleye, smoking a cigar, fiddling with various lures and talking to his unseen quarry. For a time, he had a sweet hole, a muskie-filled lake that only he fished, but the muskie mysteriously disappeared, sending him more frequently to the several other lakes on the 7,500-acre property used primarily for environmental research. He sought out Land O’Lakes when his batteries needed recharging. On rare occasions, including one emergency sojourn by the Civil Rights Commission, it was a work-related site.

On two occasions — in 1982 and 1989 — he and I did oral history there, recording during the day on the screened porch of the summer house with eagles swooping about and at night in his cabin. When the department heads in the division then called University Relations started to gather annually in late May at Land O’Lakes with their spouses for strategic planning and recreation, he, retired by that time, served as our chaplain. He celebrated a liturgy every evening before dinner, and his favorite homilies were on the meaning of the Mass and on the Holy Spirit. One night was set aside to discuss informally any topic on his or the group’s mind.

A feeling of camaraderie pervaded these gatherings; most of the people there had worked as a team under Hesburgh for years and had a deep affection for him, an affection that was returned. There also was a bonus for the retired president — he counted the “chaplaincy” as the retreat that members of the Congregation of Holy Cross were obliged to take each year.

Land O’Lakes became well-known when its name was attached to a statement signed by a group of Catholic educators and churchmen who met there in July 1967. What they issued amounted to a manifesto for Catholic higher education in North America. “The Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself,” read the key words of the document, which received national attention.

Hesburgh orchestrated the Land O’Lakes statement to affirm the model of a Catholic university in service to the Church but not juridically tied to it. Only such a university, he argued, could be “the critical, reflective intelligence of the Church.”

It was a model foreign to the Vatican, which essentially made no distinction between a seminary and a Catholic university. Rome was not comfortable with the notion that Catholic institutions of higher learning in the United States were virtually all chartered by the state and pursued their religious mission in a pluralistic society which prized academic freedom as essential to the definition of a university.

Critics charged that the Land O’Lakes Statement was designed to provide cover for the acceptance of public funds — from scholarships to research grants — without which Catholic colleges and universities could not compete for students or faculty. It was, they warned, the harbinger of the secularization of Catholic higher education.

Despite his best efforts as president of the International Federation of Catholic Universities, Hesburgh was never able to get Rome to sign off on the Land O’Lakes Statement, as proved by the 1990 papal document, Ex Corde Ecclesiae, an attempt to reassert Church control over colleges and universities that wanted to call themselves Catholic. In 1970, the American Association of University Professors honored Hesburgh with its prestigious Meiklejohn Award for academic freedom, quite a distinction for a man who for several years had to sign off on campus requests to read materials on the Catholic Index of Forbidden Books.

The two most important decisions of the Hesburgh era were the changeover to lay governance in 1967 and the decision to accept women undergraduates in 1972. In the longest (19 pages) and most widely distributed letter of his presidency, Hesburgh argued that the future of Notre Dame as a Catholic university depended on increased lay involvement as the number of Holy Cross priests available for and suited to administration, teaching and research diminished.

This lay involvement, fully endorsed by Vatican II, would not come without a sense of ownership by the laity, and for the sake of its own future and that of Notre Dame, the Congregation of Holy Cross needed to transfer the assets of a University they founded and nurtured to a new Board of Trustees and group of Fellows. There was understandable opposition within the Holy Cross community, but with the backing of the Superior General in Rome and the Provincial of the Indiana Province, lay governance became a reality.

Because of Notre Dame’s unique position in the symbolic life of the Catholic Church in America, its action had widespread impact on American Catholic higher education.

What Hesburgh did not mention in his letter to the Notre Dame family was another reason for lay governance — it removed Notre Dame from interference from Rome in affairs of the University. Hesburgh kept close in memory an earlier attempt to suppress a Notre Dame Press book containing an essay on church and state by theologian John Courtney Murray. Such pressure typically traveled the clerical chain of command from a curial cardinal to one’s local religious superior. A lay board of trustees with final authority insulated the University from threats to academic freedom engendered from Church sources.

The local ordinary was still free to denounce campus activities he perceived as contrary to Church teaching (as has happened at Notre Dame and other institutions). And if push ever came to shove with Rome itself, Vatican officials had the option of declaring that Notre Dame was not a Catholic university, a step Hesburgh once described “as akin to saying apple pie was not an American dessert.”

Undergraduate coeducation grew out of a failed merger attempt with neighboring Saint Mary’s College. Negotiations leading up to a tentative 1970 agreement to merge were often testy. Two years later, when I carried notes between Saint Mary’s officials in their ground-level box on the east side of Notre Dame Stadium and Hesburgh and Trustee Chairman Edmund A. Stephan, Class of 1933, in the University box high above the west side, I sensed that these bizarre written exchanges during a football game spelled an end to merger.

The Sisters of the Holy Cross feared that, despite Notre Dame assurances, the identity of Saint Mary’s would be swallowed up. Also, Father Joyce had voiced serious reservations about the financial aspects of a merger, particularly the payment the nuns wanted. “In the end,” summarized Hesburgh, “they wanted to marry us but not take our name or live with us.”

Notre Dame moved swiftly to admit undergraduate women on its own in 1972, a time when other highly selective private universities had either done so or were planning to do so. I would receive calls from the latter schools asking for our documentation — faculty reports, institutional white papers, consultant views, administrative committee minutes — leading up to Notre Dame’s decision. There was virtually no paperwork to be had.

While a certified member of the country’s intellectual elite, Hesburgh had an attractive, down-to-earth side. He knew how to put a minnow on an orange bucktail, and his colleagues on the Civil Rights Commission knew on which door to knock to share a nightcap.

“Father Hesburgh decided to go coeducational, and we simply did it,” I would tell disbelieving university representatives struggling with a decision that divided their constituencies, particularly alumni. In explaining the positives of Notre Dame coeducation, Hesburgh was wont to cite the civilizing influence of women on male students, which grated on feminists. We eventually got him on the right page: “If we were going to educate for leadership, it behooved us to educate the other half of the human race.”

Both the changeover to lay governance and undergraduate coeducation spoke to the leadership charism of Notre Dame’s president. If the University of Chicago were a faculty’s university and Harvard a deans’ university, Notre Dame was clearly a president’s university. There was centralized institutional control to a degree not present in many other campuses.

While this trait was not universally praised by a faculty looking for wider consultation, it was a great asset in fundraising. In the successful capital campaigns during the Hesburgh years, faculty did have input in the institutional self-study that preceded the setting of academic priorities for fundraising. But the administration, particularly the Office of the Provost, had the final say in teasing campaign priorities out of the rhetoric of academic aspiration. Key trustees, as well as major benefactors, were seen individually to get their advance agreement on monetary goals.

In these, as in other matters, it was evident that Hesburgh had, in a very real sense, created the Board of Trustees, whose members were influenced by the force of his personality. In contrast, the presidents that were to follow Hesburgh would be created by the board and would enjoy a more complex relationship with its members.

A distinctly pastoral aspect also marked the Hesburgh presidency. He thought of himself as first and foremost a priest, a mediator between God and man. He was proud of saying Mass every day, whether he was at the South Pole or in the Kremlin. Once he even smuggled altar wine into the dry Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in a toiletry bottle.

He had a personal touch, and it did not matter whether he was dealing with the widow of a benefactor, a doorman at the Morris Inn or a troubled fellow priest. He felt that what was truly revealing was how one treated people below oneself, not how one treated those above. He was careful not to inhale praise; he knew he would always be No. 00652 to the people who worked in the laundry. He did not socialize in South Bend because he figured to do so for one trustee, benefactor or friend would commit him to an endless number of invitations.

When it came to visiting the sick, comforting the dying, celebrating the Eucharist, witnessing marriages and baptizing infants, however, he was as available as he could make himself. The light in his office enticed many a student night visit via the fire escape. Some came to complain, others to go to confession.

While a certified member of the country’s intellectual elite, Hesburgh had an attractive, down-to-earth side. He knew how to put a minnow on an orange bucktail, and his colleagues on the Civil Rights Commission knew on which door to knock to share a nightcap. Small talk was for the fish, however. He tended to dominate conversations, whether the table be at Corby Hall or the Morris Inn. His extensive travels made him a “country dropper” instead of a name dropper. His timing was occasionally off; once after a sumptuous dinner for the faculty, he talked at length about world hunger.

After Nixon resigned the presidency in 1974, Hesburgh was besieged with requests for interviews. Nixon had fired him as chairman of the Civil Rights Commission two years earlier, and reporters were after the most condemning quotes they could get from old foes of the president. Hesburgh declined all interviews, explaining, “I don’t want to kick a man when he is down.” He did have a coffee cup, a gift that displayed Nixon’s photograph on a three-dollar bill. We took it off his desk when he did office interviews with the media.

A self-described political independent, Hesburgh was on good terms with other U.S. presidents. His hero for civil rights legislation was Lyndon Johnson, who awarded him the Medal of Freedom in 1964. He was caught off guard when called to the White House while in Washington one summer day in 1993, only to be congratulated by Bill Clinton on the 50th anniversary of his ordination.

A few years later, Clinton would leave intense Middle East negotiations at Camp David to present Hesburgh with the Congressional Gold Medal in the Capitol rotunda. In addition to Eisenhower, four other presidents — Ford, Carter, Reagan and the elder Bush — were hooded by him at Notre Dame ceremonies.

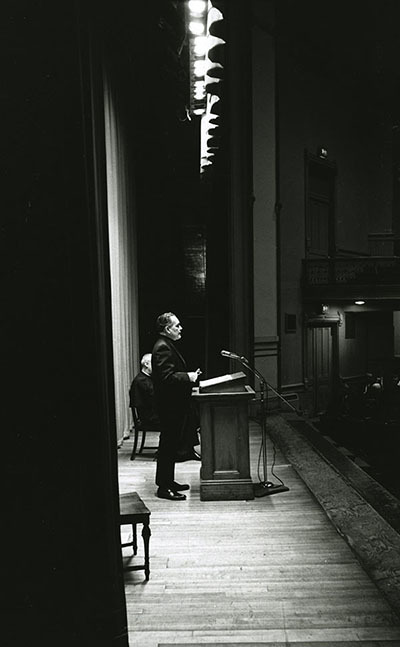

When the crowd gathered for Hesburgh’s farewell in Washington Hall, televised by satellite to alumni at 126 sites across the country, the figures for the 35-year Hesburgh era, at the time the longest presidential tenure of any major American university, were impressive. Enrollment had doubled, endowment had gone from $9 million to $400 million, annual support from $1.1 million to $48.3 million, the operating budget from $9.7 million to $176.6 million, the average faculty salary from $5,400 to $50,800, student aid from $20,000 to $40 million. Forty new buildings had been built, bringing the replacement value of physical facilities to almost a half-billion dollars.

Yet Hesburgh alluded to none of this in his valedictory. This is the way he said farewell: “To have shared with you the peace, the mystery, the optimism, the joie de vivre, the ongoing challenge, the ever youthful ebullient vitality and, most of all, the deep and abiding caring that characterizes this place and all of its people, young and old — this is a blessing I hope to carry with me into eternity when that time comes.”

Dick Conklin retired in 2001 as associate vice president of University Relations at Notre Dame and returned home to the Minneapolis-Saint Paul area, where he died in May 2013.