Editor’s note: In commemoration of the anniversary of the death of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, on February 26, 2015, Notre Dame Magazine is publishing selections from our Hesburgh Special Edition here at magazine.nd.edu. We will publish one piece per weekday through Wednesday, March 2. Print copies of the special edition are available; please visit our store for ordering information.

It seemed like a fine idea at the time. Maybe even fun.

Father Hesburgh would drive the Amish buggy. I would follow along in my car and pick up Father Ted and our dear friend David Luthy ’65 at the end of their joyride. David figured that the man who had piloted a submarine and flown in the world’s fastest airplane should check an Amish buggy off his “bucket list” of cool rides. David is Amish.

- More from the Father Hesburgh Special Edition

- The Maker of Notre Dame

- The Strength of Leadership

- The Endless Conversation

- The Long Twilight

Father Hesburgh and David have known each other since David was Catholic and joining the priesthood with the Congregation of Holy Cross. Even though David joined the Amish instead and has lived in Ontario for several decades, the two have remained friends. They are my friends, too, but my role today is to chauffeur the aging priest and Amish elder on a day-long tour of Amish country east of South Bend, Indiana.

David has scheduled stops at an Amish museum, Amish school and book publisher, and a private home for an ample meal with a genial Amish family — noddingly entertained by Father Ted’s head-of-the-table discourse on space exploration and the Amazon Basin. Now the buggy ride.

For this leg of the excursion I follow the priest and our gray-beard friend down the dusty, dirt-and-gravel road in the sunny heat of summer. The buggy sways and leans, veers and pitches side to side down the narrow lane. It’s a rolling rural byway with troublesome deep gullies on each side, and it looks like Father Ted needs all the room the slender road offers.

It’s all a kind of lark, steed and buggy jauntily careening — until the truck barrels over the hill in front of us.

Not just any truck. A huge logging truck. Fully loaded. Rumbling and grumbling downhill with the buggy in its sights. The horse-drawn carriage steered by the Rev. Theodore Martin Hesburgh, CSC. Mighty behemoth whose girth dwarfs the country lane. Neither vehicle slowing. The diesel rig threatening to destroy all in its path. It is speeding on, looming large, the collision playing out in my brain. Little black buggy. Leviathan. The squashing moment of impact imminent.

I pull the car off right, stop, shut my eyes, squeeze tight and brace for doom.

I hear the roar of 18 tires ripping loud over gravel and dirt, spewing hot air and dust into my open window. The buggy, unscathed and undeterred, clip-clops placidly on up the road. I look into my rearview mirror and watch the grim reaper disappear in a furry haze over the hill to our backs. Whew. Close call that was.

Fortunately for all of us — not just David, Father Ted and me — another decade would pass before the final call came to bring Theodore Hesburgh home to the communion of saints.

We all have Father Hesburgh stories; favorites have been told and retold. Some recount bold moves on global stages, acts of wisdom and courage on a grand scale. Others are small but meaningful maneuvers that changed the course of lives, gestures of kindness and generosity extended when no one else was watching. What they have in common is a man who had a very human heart; a visionary leader who could decipher the right thing to do, who could act decisively then stay the course of his convictions; a priest who was holy but real, who lived simply even among the world’s powerbrokers and who was humble but had a global reach.

True, Hesburgh could recount long stories about the wielding of power and influence in exotic locales with a name-drop cast. But for all he saw and did and accomplished, the man stayed grounded, remained centered in himself and his faith. He didn’t let the heights distract him from his rootedness as a Catholic priest serving the good wherever he could.

For most of his years on campus, he lived, like many other Holy Cross priests, in Spartan quarters in Corby Hall — his room was the one with the garbage Dumpster just outside the window. He said Mass daily, was as comfortable around popes and presidents, rulers and kings as he was with students, benefactors, the housekeepers and support staff. He was probably happiest at Land O’Lakes, fishing for muskie or walleye, or relaxing, reading, writing, smoking a cigar or telling his own stories, like the time a fish leaped into the boat while he was casting his lure into the water to catch one.

When I became editor of Notre Dame Magazine, I was included with other department heads in University Relations who made an annual retreat to that ruggedly pristine expanse of woods and lakes along the Wisconsin-Michigan border. Father Hesburgh was always there — just before Memorial Day, always for his birthday. He said Mass for us each evening and joined us for drinks and dinner.

Once during each visit we’d have a Hesburgh seminar, during which we’d throw some logs on the fire, pull up chairs, ask questions and let the man hold forth on all manner of topics. The range of subject, depth of knowledge and extent of personal experience was extraordinary — though the man could surely go long, supplying plenty of details and detours that the editor in me would be itchy to cut out.

On my first trip there I was re-introducing myself to Father Hesburgh when he interrupted me, said he knew who I was and began talking about my Louisiana hometown, which he had visited during his days with the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. It was the last stop, he said, before getting everyone to Land O’Lakes to hammer out the document that would become the U.S. Civil Rights Act.

So Father Ted led me to the porch overlooking a broad, serene lake and pointed to the table where the commissioners sat to review their findings, then debated, negotiated and scripted the tenets that changed life in America forever. It was the first time I heard the story about Hesburgh taking the commissioners there, with him explaining how he had brought them together — Northerner and Southerner, Republican and Democrat — to fish. And how they had fished for several days before talking business near the end of their stay. And how the relationships and common love for fishing had oiled the gears of deliberation, their humanness begetting their resolve for justice.

The setting was the same for the conclave that yielded the 1967 Land O’Lakes statement, the watershed moment in Notre Dame’s bold experiment to be both Catholic and a world-class university. I was a peripheral character during those days of the University Relations meetings and talks at Land O’Lakes, an observer of this communal accord of leadership, wisdom and caring. But on a few occasions I followed Father Ted back to his tiny, cluttered cabin to talk, ask questions, listen and learn. Despite the rustic setting, I knew I was in the presence of greatness — although I was always struck, too, by how down-to-earth he was. Hesburgh was grounded, genuine and unpretentious. He was comfortable in his own skin, straight and true to his God.

A question could send him down surprising pathways — flying co-pilot in the cockpit of the world’s fastest plane, serving as chaplain to the newlyweds in Vetville, pardoning Vietnam War protesters, helping to launch the Peace Corps, brokering deals on atomic energy between the United States and the Soviet Union, fending off mass starvation in Cambodia, or walking the hills near Jerusalem for the spot to build Tantur. As I listened to him recount his tales, I could not help but think this man had no wife to come home to, no family to hear about his latest trip or to ask how his day was, no proud children or grandchildren sitting at his knee.

Despite all the orbits in which he operated, he’d strike up a conversation with most anyone he encountered on campus. He talked straight, dressed like a father, had incredible stamina, and when he retired and moved into his top-of-the-library office he would get off the elevator a few floors short of his stop and walk the last few flights of stairs for the exercise. He declined an invitation to join the College of Cardinals, kept a pope’s ring in a drawer and judged people on their own merits, not their position, pedigree or wealth. On the day of our Amish adventure he provided me two more vivid images that still make me smile.

On a stop while heading back to South Bend, Father Ted is draped in a Columbo-style trench coat and clutching the cup of coffee he had bought at the McDonald’s in a Toll Road rest area. When I spotted him waiting for me in the soiled, bustling lobby, he seemed curiously comfortable and out of place: this close friend of Joan Kroc (head of this whole vast global McDonald’s enterprise), this globetrotting humanitarian dignitary indistinguishable from his common, fellow travelers at this most human of stops along the Heartland interstate.

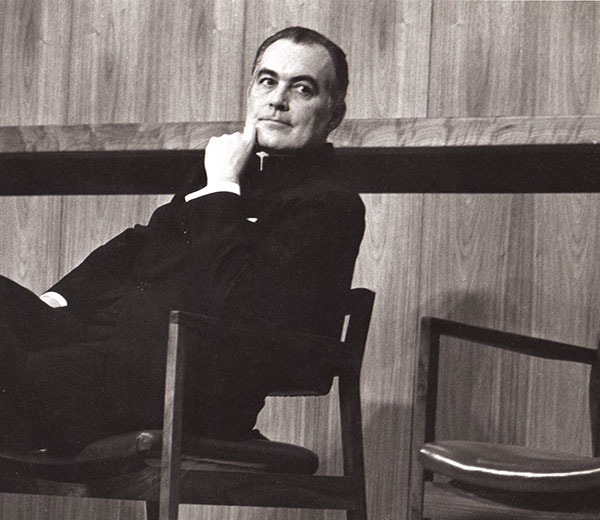

Earlier that day he had worn David Luthy’s round, black, wide-brim Amish hat to shield him from rain and said he had worn a similar hat as a young priest in Rome. He then looked to me like an Old Testament prophet or Old West explorer gazing out over the Promised Land. Hesburgh had a face suited for magazine covers as a young man, and later the dignified countenance of a national hero to be sculpted in stone or bronze.

When I was a student in the early 1970s, Hesburgh had been president for 20 years. He was a forceful proponent of civil and human rights, and had gained national notoriety for hard-lining student protest while standing as a conscience against war and nuclear weapons. He was one of the most visible symbols of Catholicism worldwide, and through various boards, foundations and commissions he was combating poverty and oppression on a global scale.

These engagements in world arenas (he would travel 150,000 miles annually fulfilling those obligations) had spawned campus jokes — like the reference to the statue of Moses pointing skyward at the airplane traffic overhead and noting, “There goes Hesburgh.” Yet students really did scale Main Building stairwells and fire escapes in the early morning hours to visit with the night-owl president whose office light glowed amber long into the night and who invariably invited interlopers into his office for a visit.

Even in my early years as a very minor employee at Notre Dame, I received handwritten notes from the perpetually involved world-traveler complimenting me on a story I’d written or thanking me for the smallest things. He had a human touch that gathered loyalty and affection with a strong gravitational pull.

In his twilight years Hesburgh still had a grasp of campus; he didn’t miss much. He retained keen, on-target observations about the place and its people. I told him more than once, and made the point when speaking publicly, that I had always seen Notre Dame Magazine as an extension of his vision for the University and that I had spent my time as editor trying to make the magazine true to that mission.

As a young alumnus, I was moved by some pieces Hesburgh had written defining the Catholic university in this modern era. He explained the need for institutions that pursued truth with the most rigorous intellectual and scholarly aspirations while situating research and scholarship within contemporary Catholic thought and the moral, ethical and spiritual dimensions of mankind’s most pressing concerns. I came here to work because I wanted to be part of that. As a believer in the truth-seeking endeavors of both journalism and education, I wanted in on that conversation for the global good, and I readily saw what role the University’s magazine might have in furthering those aims of enlightenment and understanding.

Hesburgh was always a supporter of the magazine, a firm defender of its autonomy and position. In 1985, the Notre Dame president, talking to a group of university magazine editors meeting on campus, said their publications should provide continuing education. “Write about national and international problems,” he said. “And don’t be afraid to criticize the university. Don’t be afraid to make the alumni angry. Let your readers scream back at you. Don’t be afraid of disagreement. The magazine should challenge readers to do some thinking.”

He preferred — his life was testimony to this — the value in taking a thoughtful and well-reasoned stand to shying away from tough topics.

When the magazine staff began work on this issue, I told Father Ted what we were up to and that some writers would be contacting him for interviews. “You do what you’ve got to do,” he wryly noted, unperturbed we were embarking on a commemorative issue to be published after his death. It was no easy task to bring such a life into so few pages, a life touched by so many with memories, appreciations and stories to tell.

I remember Jim Frick, the long-time vice president for University Relations, telling me about Hesburgh’s years representing the Vatican during nuclear arms talks in Vienna for the United Nations. He was seated next to the Soviet delegate who rebuffed any pleasantries the priest offered. But Hesburgh noticed a woman in the gallery who exchanged nods daily with the Soviet leader. One day she wasn’t there and Father Hesburgh found out why: She was in the hospital. Father Hesburgh sent her roses, and his friendship with the couple was formed — one that lasted for decades and benefited both Notre Dame and U.S.-Soviet relations during the Cold War.

One of the writers whose story I most wanted told was Robert Sam Anson ’67. Anson had been the founding editor of The Observer, the independent student daily launched during the old student unrest and the protest days. Hesburgh had later pulled made a phone call to get Anson out of Cambodia when he was captured while covering the Vietnam War for Time magazine.

Anson was sheepish about seeing the priest after all the years in between. He asked if I would intercede on his behalf and make sure the coast was clear for Anson to contact him. I didn’t know why until I raised the name with Hesburgh. The eye-roll and groan said enough.

Anson, said Hesburgh, had been a harsh and relentless critic of the University president on The Observer’s pages — mean enough that, independent of each other, both Anson’s mother and sister had called the priest, asking him to boot the malcontent out of school. Hesburgh declined, he recalled, despite his irritations, because any retaliation would negate all he said and believed about the freedom of the press.

Still, when the Time editor called and told Hesburgh that the priest was their only hope for getting their imprisoned correspondent out of captivity, he weighed the decision. In the end, Hesburgh concluded, “I figured that as a graduate he was still a member of the family. Besides, I wouldn’t be much of a priest if I didn’t believe in forgiveness.”

So Hesburgh picked up the phone and called Pope Paul VI. The pontiff had been given an honorary degree from Notre Dame in 1960 when he was Cardinal Giovanni Montini. “I told him,” Hesburgh recalled, “that because of the honorary degree, he and Anson had the same alma mater and he should do what he could to help.” Three weeks later Anson emerged from the jungle intact.

This story is a favorite of mine. I like the marvelous practicality of his calling the pope, and I like that Hesburgh supported the rights of student journalists even when they used those shields to give him grief. Throughout his life he had a confidence, self-restraint and panoramic outlook that enabled him to stand apart from the rest. The story’s turns and layers reveal a lot about the man — his principles and his loyalties, the importance of relationships, the generosity of his spirit and his clout, the refreshing humanness and the priestly values of forgiveness and redemption. He was a man of honor, a man with a conscience, a priest who called on the Holy Spirit to grace his days.

The trait I most appreciated — from my outlying orbit in the spheres of his life — was the man’s ability to see into a situation, usually a knotty, thorny complex of competing forces, and to see — by his own lights — the right way through. Once he had discerned that path, he had the resolve and dexterity to move the players and the pieces to get his mission accomplished. And in the process — despite the difficulties and the foes — he gathered respect, admiration, even love. The man was loved. He was loved.

Hesburgh left his mark on the world, Our Lady’s university, the people whose lives he touched in big and little ways. We’ll all miss him. But we’re also now obligated to carry on, to move forward in the ways he showed.

Kerry Temple, who joined the staff of Notre Dame Magazine in 1981, has been its editor since 1995.