Editor’s note: In commemoration of the anniversary of the death of Father Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, on February 26, 2015, Notre Dame Magazine is publishing selections from our Hesburgh Special Edition here at magazine.nd.edu. We will publish one piece per weekday through Wednesday, March 2. Print copies of the special edition are available; please visit our store for ordering information.

Monday: The Endless Conversation by Andy Burd ’62.

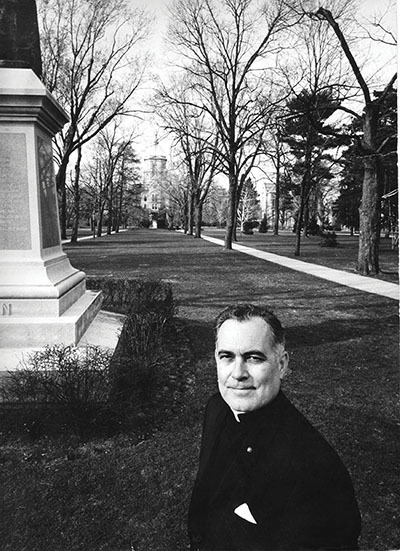

By any measure, Father Theodore M. Hesburgh’s influence on higher education — both during the 35 years he served as president of Notre Dame and over the many years after he retired — was oversized: broad, deep and enduring, touching everything from athletics and academics to the very essence of what makes a modern university, especially a modern Catholic university.

When the nation’s campuses rose in revolt in the 1960s he took a hard line that set an example for other university presidents, but when the Nixon White House wanted him to help draft laws expanding the federal role in quelling campus dissent, he told the president to back off. He helped lead the way for Catholic higher education’s independence, and he challenged all institutions affiliated with the Church to reject mediocrity. He fought for a clear definition of what it means to be a Catholic school where all ideas are tolerated and where faith is lived truly, every day. And he established an illustrious standard for what a university president could be, a record that, like Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak, inspires but may never be equaled.

“When you look at the men who were in university leadership roles since World War II, Father Ted cast a very strong shadow as moral leader among us,” said William Friday, the University of North Carolina’s much-respected former president who, along with Hesburgh, was a founding co-chairman of the influential Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. “I would put him at the very top, and I think most of the colleagues I worked with would do the same. You always knew the strength of moral judgment would be brought to bear in decision-making when Father Ted was involved.”

In any ranking of the most effective university leaders of the 20th century, there is widespread agreement that Hesburgh’s name should be in the top rank. But in terms of the respect with which the academy regarded what he did and what he said, it is widely agreed that he has no peer.

“Within the higher education family he is a towering figure,” said Robert H. Atwell, former president of Pitzer College in Claremont, California, and later president of the American Council on Education. It was at the council that Atwell realized top business executives and the presidents of other schools were willing to volunteer their time and money simply for a chance to be in the same room with Hesburgh. He was by all measures, Atwell said, “one of the giants.”

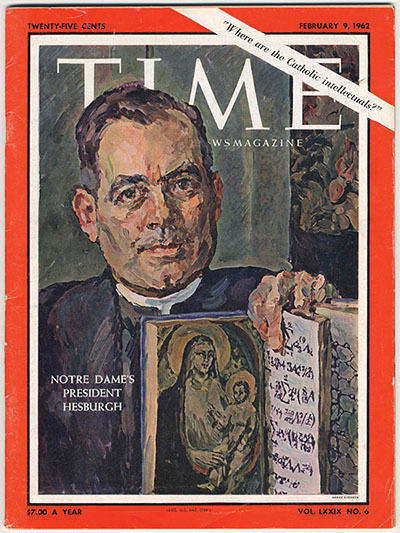

As far back as 1962, when he was completing his 10th year as president, Hesburgh appeared on the cover of Time magazine, looking like a young Dan Rather in a turned-around collar. Although he hadn’t yet realized his most important accomplishments — the campus was still a clubby, all-male place wholly owned by the Holy Cross fathers — Time called him “the most influential figure in the reshaping of Catholic higher education in the United States.” His influence spread across the higher education landscape, but it was felt most keenly within Catholic higher education, where he led what has amounted to a full-scale revolution that has touched practically every American college and university connected to the Catholic Church.

Empowering the laity

The scene that Time magazine described in 1962 was one in which an energetic young Hesburgh attempted to bring a measure of academic success to his own campus, where football and theology reigned supreme. He held onto a different notion of what Notre Dame could be, and as he attempted to push the University toward becoming a “Catholic Princeton” he realized that one obstacle wouldn’t yield to minor tinkering but required a wholesale transformation.

The University had been controlled by the Holy Cross fathers since its founding in 1842. By the early 1960s, Notre Dame had become a complex institution whose operations required expertise that often exceeded the order’s abilities. This was not, Hesburgh realized, just a recruitment problem. He saw it as the opportunity to put into practice a theory he had formulated 20 years before. At Catholic University of America in 1945, he had written his doctoral dissertation on expanding the role of lay Catholics in running the Church. “Ninety-nine point nine percent of the church’s members are laymen, and I thought they should have a really important and significant role in the life of the church,” Hesburgh said in a telephone interview in 2005. “Many of them are highly motivated, and it was clear to me that we were entering the age of laymen.”

- More from the Father Hesburgh Special Edition

- The Maker of Notre Dame

- The Endless Conversation

- The Long Twilight

- The Right Side of the Road

He was referring to the pronouncements then coming out of the Second Vatican Council, which vastly broadened the role of lay Catholics in the affairs of their Church. In the summer of 1965, preliminary discussions were held on the front porch of the summerhouse at the Holy Cross fathers’ Land O’Lakes retreat in Wisconsin. Surrounded by birdsong and dense woods, Hesburgh walked his order’s superiors through the radical change he proposed. They were in basic agreement, but he expected opposition from Holy Cross priests who could not see the sense of giving away what was then an asset estimated to be worth half a billion dollars. Some of them also believed that lay leaders would not care for the University with the same passion as the priests.

But a consensus was reached, and the decision was made. A special provincial council in 1967 approved the change, and then, using the order’s strong contacts in Rome, the Vatican was petitioned to authorize the transfer, a process called alienation. Paul C. Reinert, S.J., was taking St. Louis University through the same steps at around this time, but with a much lower profile.

Many other Catholic institutions were keenly aware of what Hesburgh was doing at Notre Dame. Just before her death in September of 2005, Monika K. Hellwig, past president and executive director of the Association of Catholic Colleges and Universities, which represents most Catholic institutions of higher learning in the United States, Canada and the Middle East, praised Hesburgh for his role in the evolution of Catholic education. “He set a model for other schools to incorporate separately,” she said, “and almost all our colleges have followed that model.”

Hesburgh helped launch a sea change, and a higher education disaster was averted. With their newfound independence, the Catholic schools became more adept at handling the critical tasks of modern institutions of higher learning. Professional administrators kept the places running efficiently, and multimillion-dollar budgets were taken over by people with real-world financial experience. Endowments grew, campuses expanded, and the extra resources were used to increase the quality of Catholic education. Hellwig said the Catholic colleges and universities also had been “horribly at risk” when the separate religious orders owned them and assumed the legal liability for guaranteeing their existence. Transferring ownership to lay boards protected many smaller orders from ruin.

Hellwig also said that the other schools were intrigued by the way Notre Dame had set up a board of fellows made up of clergy and laymen in which principal authority was shared equally between six members who were Holy Cross priests and six laymen who were graduates with expertise in such fields as banking, business and law. And because they were ND graduates, she said, they were people the religious could trust would understand “what a Catholic university should be.”

One of the biggest concerns at the time of the big changes was the risk that by adopting this model, Notre Dame — and the schools that went down the same path of turning control over to lay boards — would become less Catholic or, in some extreme cases, not Catholic at all. But Hesburgh’s confidence that this was the right way helped many other institutions get through the tough transition. His own conviction that lay control was a good thing never wavered. “I think we are more Catholic today than we were in the past — both big C and little c,” Hesburgh, along with Jerry Reedy, wrote in his best-selling memoir God, Country, Notre Dame. “One could argue with that, and many do, but I stand by that statement.”

Academic freedom

His bold steps in South Bend and Rome made Hesburgh a lightning rod for criticism of Catholic education in the United States. Lay boards only added to the confusion over what a Catholic university in the 20th century really was.

Hesburgh was already familiar with the pitfalls and hidden traps of that debate. One of the first organizations he belonged to outside of the Notre Dame campus was the International Federation of Catholic Universities. In 1963, he was asked several times to run for president of the group, but he always said no. He was elected president anyway, but before he could take control of the moribund organization he was summoned to the Vatican and told the election was invalid. Canon law had not been followed, he was told. When Hesburgh questioned the Vatican officials about what aspect of canon law had been violated, he was shocked by the answer. The archbishop in charge told him that the president of the organization had to be president of a Catholic university, and that particular archbishop did not consider the University of Notre Dame to be a Catholic university.

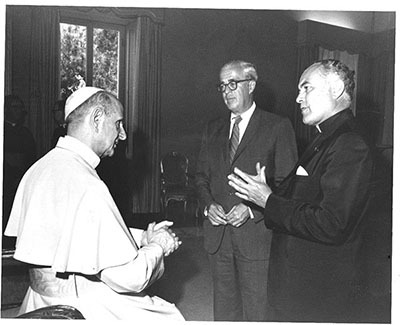

The dispute turned as much on foiled personal ambition as canonical interpretation of the University’s nature, and it was straightened out when Hesburgh sent a note to Pope Paul VI advising him of what was being done in his name. But the broader question remained unsettled: What is a Catholic university?

In 1967, Hesburgh went back to Land O’Lakes. This time, he gathered a number of university presidents and administrators to work out a coordinated position on the autonomy of Catholic universities in the face of attempts by the Holy See to assert authority over the schools. For the first time, American Catholic higher education focused intently on the issue of academic freedom. The Land O’Lakes meetings produced a written document that became a turning point in the history of Catholic education in the United States. This “symbolic manifesto” was a declaration of the independence of Catholic colleges and universities and their dedication to the pursuit of truth wherever it might lead.

While respecting the Vatican’s role in theology and doctrine, the proceedings at Land O’Lakes were an attempt to loosen Rome’s tight control over what could be taught in the classrooms, and by whom. At the same time, the manifesto also affirmed the most fundamental nature of the Catholic university as “a community of learners or a community of scholars, in which Catholicism is perceptively present and effectively operative.”

The Land O’Lakes statement is inevitably linked to Hesburgh. “He shaped the response of American colleges and universities to Rome,” said Hellwig. But certain parts of the American Church also connected Hesburgh’s role in the Land O’Lakes conference to the “wholesale loss of Catholic identity,” at most Catholic institutions. That phrase comes from the mission statement of Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia, one of a small group of conservative Catholic schools founded after the Land O’Lakes meeting.

When Hesburgh questioned the Vatican officials about what aspect of canon law had been violated, he was shocked by the answer.

Other parts of Christendom College’s raison d’etre reveal a particular mindset that Hesburgh and the others had challenged in 1967: “The cultural revolution which swept across the United States in the late 1960s struck a devastating blow to Catholic higher education,” the Christendom mission statement notes. “The damage became evident with the Land O’Lakes statement in 1967, in which Catholic universities formally broke their ties with the teaching Church and repudiated their duty of obedience to her. There followed a wholesale loss of Catholic identity in these institutions. Not only were crucifixes stripped from classrooms, but the foundations of Western civilization were stripped from the curricula. The very existence of objective truth and absolute moral principles was denied, explicitly or implicitly.”

Although this is the view of a minority of Catholic educators, its survival to this day is an indication of how difficult it was for Hesburgh to have marshaled the forces for academic freedom in 1967. And the Land O’Lakes statement was not the end of the debate. Hesburgh held meetings of the International Federation on the issue of academic freedom through much of the 1970s, then in 1990 Ex Corde Ecclesiae, the pontifical document on Catholic higher education, set off an even more passionate debate about the identity of Catholic education that continues today. But Hesburgh’s leadership of the Land O’Lakes conference in 1967 played a seminal role in the process of determining what makes an American university Catholic.

The actions of a few

In the turbulent 1960s, Notre Dame experienced its own campus unrest, not unlike many other universities around the country. The protests and lie-ins were less violent there than in other places, but because they were staged at Notre Dame they drew a sharper profile. And because Hesburgh was president, they were handled in a way other university presidents could only marvel at. Notre Dame students threatened to burn down ROTC buildings, and they lay down in front of buildings to disrupt recruitment drives by the CIA, Dow Chemical and other companies targeted by student radicals opposed to the war in Vietnam.

In 1969, Hesburgh finally had had enough. He issued what became a well-known letter, setting down in clear terms his own dim view of the disturbances. His criticism was not based on his judgment of the moral value of what the students had to say, nor their unquestioned right to state those views. Rather he believed the actions of a few could not be allowed to interfere with the rights of the many.

The letter took a hard line — a 15-minute line. Hesburgh warned all students whose actions infringed on the rights of others that they would be given “15 minutes of meditation to cease and desist.” If, at the end of that time, they were still involved in the disturbance, they would be suspended and given another five minutes to reconsider their actions. When that deadline passed, protesters still obstructing the rights of others would be expelled.

The letter struck a chord and was noticed far beyond South Bend.

“At a time when most university presidents were backfilling, compromising and getting from one day to the next, Ted was much more courageous and forthright in standing up and saying to student demonstrators, ‘You’re not going to behave in this fashion,’” said Derek Bok, former president of Harvard. “He showed a toughness you didn’t find very often in those days. I admired him for it, and a number of people did.”

Hesburgh’s no-nonsense letter also caught the attention of the Nixon White House. After reading about the situation at Notre Dame, President Nixon sent Hesburgh a congratulatory telegram and asked him to help put together a tough new federal response to student violence.

Hesburgh had become the darling of right-wing hawks for standing up to the demonstrators, but he felt they had misjudged his motives and his politics. He responded to Nixon’s invitation with a note saying that the best way for the federal government to handle the university situation was to allow the university community “to save itself.” He discouraged any effort to expand federal powers on campus and politely told the White House that if the day ever came when universities felt they needed federal help, they would not hesitate to ask for it.

The anti-war campus unrest continued for several more years, and in May of 1970 the Ohio National Guard opened fire on student demonstrators at Kent State University, killing four and wounding nine. But it is sobering to imagine what might have happened if Hesburgh had not discouraged the Nixon administration from taking a tougher line on student violence.

For a long time, Hesburgh kept a small card in the inside pocket of his jacket. On the card was a running list of the presidents at other universities who had been forced to resign or who had died in office, often, he suspected, from the unbearable strain of trying to keep the places running in the face of so much controversy. The list included the names of Clark Kerr, the University of California president who was dismissed by Gov. Ronald Reagan in 1967 when student protests spiraled out of control, and Courtney Smith, the Swarthmore College president who died of a heart attack during a student takeover of the college admissions office in 1969.

“It was one of those little yellow sheets, with two columns on one side and three on the other,” Hesburgh once recalled. “I got up to about 250 names and thought this was a useless process, so I packed it up. Some of my best friends, from the best universities in the land, were on that list. It was a sad list.”

Raising the bar

It was a tough time to be a university president. And while it wouldn’t be fair to say that Hesburgh made being president look easy, he did make it seem a task that could be achieved with good will and grace. He kept Notre Dame running smoothly, and growing rapidly, with energy enough left over to be involved in the heavy lifting of special groups like the Carnegie Commission on the Future of Higher Education and the Knight Commission on Intercollegiate Athletics. Part of the reason he was able to do so much was his extraordinary partnership with Father Edmund Joyce, executive vice president and number-two man at Notre Dame for the 35 years Hesburgh was president. Joyce died in 2004.

“Ned Joyce read every paper I ever got from the Knight Commission, and I never said a single thing that he didn’t agree with me was the right thing to say,” Hesburgh once noted. “We were never at cross-purposes in these things.”

Hesburgh abhorred the win-at-all-cost attitude that he believed had distorted college athletics. When he and Bill Friday served on the Knight Commission he used that large stage to focus attention on the imbalance between athletics and academics. Because he represented Notre Dame, his views carried great weight. “We’re not in the entertainment business,” Hesburgh said in 2001. “The things we’re supposed to do we’re not doing.”

He pushed the commission to recommend drastic changes, and one of the results was the Academic Progress Rate, APR, which was supposed to restore a degree of importance to university academics over sports and ensure the balance was not lost again. A passing rating of 925 roughly translates into a 50 percent graduation rate for athletes — a modest goal Hesburgh passionately believed was the least major schools should achieve. Universities that failed to meet that standard stood to be penalized and their scholarship students prohibited from playing.

Today the system still is far from perfect. In the 2011 NCAA tournament, for instance, 10 of the 68 basketball teams fell below the 925 rating, which would have made them ineligible to play in the tournament under the Knight Commission’s proposed guidelines. The Secretary of Education, Arne Duncan, has strongly supported the commission’s proposal and has agreed with another of the commission’s recommended actions, which would require that some of the NCAA tournament revenues be redistributed to teams that achieve the highest academic standards.

The presidential pulpit

Besides attempting to reform collegiate sports, Hesburgh was a driving force on many other commissions and study groups that examined a range of critical issues, including public funding of independent universities. Derek Bok nominated him for the Harvard Board of Overseers, and in 1994 he was elected president of the board, the first Roman Catholic priest to hold that position or any other on the board.

“I nominated him because I thought it was good to have people who really understood academic institutions on our boards,” said Bok, who was president of Harvard for 20 years. “And like everyone else who knew Ted, I thought of him as a natural leader, someone everybody turns to and listens to with a great deal of respect.”

As an outspoken moral leader of American society, Hesburgh naturally followed the tradition of such great university presidents as Nicholas Murray Butler, who led Columbia University for 43 years and shared a Nobel Prize, and Charles W. Eliot, an influential education innovator who was president of Harvard University for 40 years. That Hesburgh was able to accomplish all he did during the turmoil of the 1960s, and through the pendulum-swing back to campus conservatism that followed, is a most remarkable achievement, a gold standard for a disappearing breed of university leaders.

Jack Peltason, former chancellor of the University of Illinois and former president of the University of California and the American Council on Education, said that beyond being a university president, Father Hesburgh was also a priest who took his role as moral leader seriously. “He used the pulpit of his presidency for some pretty important causes,” Peltason said.

It is hard to think of a single contemporary university president who fills the same role in society today as Hesburgh did in his career. Most university leaders now are content to keep a low profile that does not in any way cause discord which would hurt their fundraising efforts.

One notable exception was Lawrence H. Summers, who, as president of Harvard from 2001 to 2006, pushed his university to re-examine itself, to challenge established modes of thinking and to shake off some of the lingering legacy of the 1960s. In many ways, Summers was the opposite of Hesburgh — brash where Hesburgh was cultured, pugnacious where Hesburgh was tough but fair, and provocative for the sake of provoking whereas Hesburgh always had a point to make. Yet, when Summers got into trouble in 2002 for taking a hard line on Harvard’s relationship with Cornel West, one of its faculty superstars, Hesburgh sent Summers a letter of encouragement.

“I told him he’s doing things that he ought to be doing,” Hesburgh said in an interview years later. He said Summers’ outspokenness was probably disquieting Harvard. “He may not survive that,” Hesburgh commented. “But to say that a university president should never say anything controversial is insane. University presidents should be among the intellectual leaders of the country. If I had never said anything about civil rights, we wouldn’t have the laws we have today.”

Of course, West left Harvard for Princeton and Hesburgh was right about Summers, who resigned in 2006. But in the current academic world, leaders like Summers and Hesburgh are anomalies. Presidencies have been reduced to an average six-year term during which most attention is focused on administration and fundraising and little effort is expended on taking tough moral stands because doing so might hurt a capital campaign. It’s not that university presidents are silenced; rather, they censor themselves. The approach outlined by John Sexton, the president of New York University, probably stands for the attitudes of many.

“[T]he paramount and superseding duty of the president is to safeguard the fragile sanctuary for dialogue within the university,” Sexton said in an address a few years ago. “In service of this end, I believe it is essential for the university’s leader to refrain generally from expressing views publicly on any issue that is not centrally related to the core mission of the institution; to do otherwise would compromise the moral authority of the presidency in the forum and undermine the credibility of the leader’s commitment to the role as guardian of that dialogic space.”

Hesburgh obviously believed a university president should follow a different set of rules. By going down that road, he set an example that has inspired many, even if they could never duplicate it.

“He did have an impact on me, yes,” said Leon Botstein, president of Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, since 1975, longer now than Hesburgh’s 35 years as president. Like Hesburgh, Botstein has used his four decades at the helm to pursue a vision of a radically transformed institution. Under Hesburgh, Notre Dame became “a world-class, diverse university,” he said. “That is an achievement that is only possible with duration of leadership, and by committing your soul to an institution.”

Botstein also said what many other presidents have expressed — that there is a certain tragedy to Hesburgh’s remarkable role in higher education, and that is, in Botstein’s words, because he was “so evidently an exception.”

“There is not going to be another Hesburgh,” he said. Not in the Catholic community. Not in the higher education landscape. Robert Atwell of the American Council on Education said as much: “There’s nobody who could fill his shoes.” Derek Bok of Harvard said Hesburgh was “among the last of the people who could combine being president of an institution and being an important figure on public issues and matters of morality.” Jack Peltason of the University of California called him “a splendid soul,” whose influence on higher education is vast and enduring but will probably never be replicated.

Such talk used to make Hesburgh uncomfortable. He was just a priest, he liked to say, and proud of it, a priest with a knack for doing a few things better than might be expected. “If I had to describe myself I’d say that I’m essentially a storyteller,” he said once. “I think that’s what I’ve been doing here all this time, telling stories.”

One of those stories involved the time, just after he was named president of Notre Dame, when he went back to Syracuse to visit his parents and sat down with his father, Theodore, for a game of Scrabble. The old man was a whiz with words and an absolute shark at Scrabble. Of course, he beat the newly minted Notre Dame president just as handily as he had always beaten the young priest. The old man turned to his wife, Anne Marie, and complained, “They just don’t make college presidents the way they used to.”

Just about everyone in American higher education would agree.

Anthony DePalma covered higher education as a journalist with The New York Times. He is now writer-in-residence at Seton Hall University and author, most recently, of City of Dust: Illness, Arrogance, and 9/11.