Illustration by Gary Hovland

Illustration by Gary Hovland

They’ve come from some of the best universities in the United States and gathered here, in the ornate ballroom of Dallas’ Hall of State, to spend a beautiful spring weekend discussing their budding political movement. Picture three dozen ambitious college students, a mix of liberals and conservatives, all clad in suits and dresses, representing the likes of Duke and Notre Dame and the University of California, Berkeley. Looking across the room, it’s not difficult to imagine the future leaders of our country: politicians, diplomats, titans of industry.

They take turns speaking into the microphone, their ideas and opinions echoing through the expansive art deco building. Incorporating impressive vocabularies that could double as SAT prep guides, the students discuss everything from the potential follies of identity politics to the threats posed by neo-Nazis. They talk about how schools should respond to sexual assault allegations, the boundaries of free speech and the use of the N-word on campus.

In the middle of the room is Rogé Karma ’18, a charismatic 22-year-old from southern California. He intervenes periodically to focus the conversation, making thoughtful points that have many in the group nodding in agreement. Sometimes he just pops in with a snappy quip to lighten the mood.

Karma is a natural speaker, at ease in front of a crowd, and today he’s a bit giddy. This is the inaugural Bridge Summit, a three-day gathering designed to bring together students from BridgeUSA chapters across the country. Attendees will have the opportunity for a group conversation with former CIA operations officer and 2016 independent presidential candidate Evan McMullin. They’ll also hear from Ohio Gov. John Kasich. But they’ll spend the majority of their time talking to each other and proposing solutions to problems.

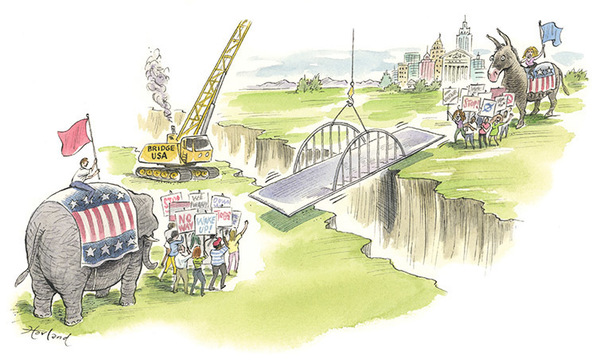

Karma conceived BridgeUSA as a response to America’s widening political divide. He envisioned it as more than a college club, as something that could morph into a grassroots movement and help unite the country through respectful discourse and open-mindedness. The goal was simple: Get people to talk to each other. Especially people who disagree, or who come from opposite ends of the political spectrum.

This April weekend is the culmination of his original idea, a meeting place where engaged college kids from different schools, backgrounds and political leanings could come together to discuss how to further the Bridge movement.

The Saturday conversation goes 45 minutes over schedule, pushing back lunch, but no one seems to mind.

Karma grew up in the fairly conservative California town of Temecula, but his family didn’t pay much attention to politics. No one watched the news or talked about politicians. Instead, the Karmas focused on sports — all five sons played hockey — and performance in school. Rogé’s father worked in real estate, later transitioning to textbook sales; his mother stayed at home with Rogé and his younger brothers, a set of identical quadruplets.

Photo by Barbara Johnston

Photo by Barbara Johnston

“I was born to be a bridge person,” Karma says. “I was the one non-quadruplet brother, and I was the liaison between my parents and my brothers. It’s also why I’m very outspoken — you had to fight to get a word in at my house.”

When Karma started his freshman year at Notre Dame in 2014, he was excited. He imagined college as a marketplace of ideas where he might discover his political beliefs and learn more about himself as a person. He was frustrated, though, by the campus Democratic and Republican organizations. They were perplexed by his desire to debate topics. One person actually laughed at him. The parties had already decided where they stood on most issues — so why discuss them?

Karma felt, as he often puts it, “politically homeless.” Eventually he stumbled upon a group of campus moderates who called themselves BridgeND. This was the best political fit he’d found yet, so he joined — but soon realized that the members of BridgeND were mostly in agreement. Karma wasn’t learning, and he was no closer to figuring out what he believed. So at the end of the semester, he stepped up to become the group’s president, explaining that he wanted to transform the club’s purpose. BridgeND, he told them, would become a place where people from across the political spectrum could come together to talk and to better understand one another.

“It’s not about policy, it’s about discussion,” he says. “I wanted to bring together partisans, nonpartisans, extremists, moderates, everyone under the sun — anyone willing to come.”

Over the next year, BridgeND’s membership jumped from eight to 50 people. Under Karma’s leadership, the group hosted events that grabbed attention by creating volatile combinations. At their first annual Melting Pot event, the group invited the College Democrats, College Republicans, GreeND, Right to Life, Women in Politics and the Student Coalition for Immigration Advocacy for a panel discussion of immigration. More than 200 people showed up to watch what they assumed would be a bloodbath. In the end, attendees walked away surprised and enlightened. Some of the speakers’ opinions subverted expectations — for example, the anti-abortion group representative’s ostensibly more liberal views on immigration.

“It totally blew conceptions of where you could lie on the political spectrum and what conventional labels are,” Karma says.

In 2016, a University of Colorado student named Courtlyn Carpenter contacted Karma to ask if he could help her start a Bridge chapter at her school. Together, they cofounded BridgeUSA, transforming Karma’s fledgling idea into a national organization. Bill Shireman, a Berkeley journalism professor and CEO of Future 500 who calls Bridge the “next phase of the American experiment,” reached out and said he knew some students who’d be interested in doing something similar at his university. Arizona State soon jumped on board, too. Within two years, Bridge chapters had formed on 22 campuses.

When Ross Irwin told people in his California hometown that he was going to Berkeley, they’d tell him to be careful around all those evil liberals. When he got to Berkeley, he found a vastly liberal campus that assumed rural America must be evil for electing Donald Trump.

“I thought, ‘These people obviously haven’t talked to each other because they would realize that neither of them are evil or stupid — they’re just different humans,’” Irwin says.

Anthony Lusardi, who helped found a Bridge chapter at Oregon’s Linn-Benton Community College and is working to start one at Oregon State, says he is “not a political guy.” But, because Linn-Benton is a school where two counties — one liberal, one conservative — overlap, he recognized the potential for tension — and dialogue.

“I’ve always admired and appreciated someone else’s perspective, even if I don’t like it or don’t understand,” Lusardi says. “It helps me become a better person: I see that in myself, and I want it for other people.”

While getting people to talk to each other might sound like an uncomplicated endeavor, it’s sometimes proven difficult. People are skeptical of Bridge, and at times its attempts to facilitate free speech have gone awry. When the Bridge group at Berkeley struck a deal with College Republicans to bring conservative firebrand Ann Coulter to campus for open discussion, the event fell apart — threats of violence led to a cancellation, igniting a media firestorm.

Karma himself experienced a personal crisis following the 2016 election. He worried that Bridge was complicit in the Trump phenomenon; that he was providing a platform for people who espoused racist and misogynist views. He wondered if Bridge was somehow hurting the country. But after going to Jerusalem to study, and witnessing up close the effects of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, his doubt evaporated.

“I saw what happens when people build walls instead of bridges,” he says. “There’s demonization and dehumanization. Bridge is the ultimate humanizing experience.”

But even if he has decided that Bridge is the best medicine for a divided country, it doesn’t mean that Republicans and Democrats agree. Though Bridge aims to keep its membership varied — Karma himself leans liberal, though he retains his sense of political homelessness — those on the outside tend to believe that Bridge is a shill for the opposite party.

“Walking the fine line between being nonpartisan and balancing the hate of the Republicans and the hate of the Democrats is very difficult,” says Manu Meel, a Berkeley student and BridgeUSA’s CEO. “Two years in — now we’re getting used to it.”

“Is cereal soup?”

That’s one of Karma’s favorite ice-breaker questions. It’s best employed at the beginning of Bridge meetings, before things get heated during sensitive political debates. It makes people laugh; it relieves tension. It allows them to see each other as people — and even as potential allies, since the lines of the cereal-soup debate have yet to be incorporated into political ideology. So although it’s a silly question, it is emblematic of what BridgeUSA does, carrying the potential to unite liberals and conservatives in unexpected ways.

On the last day of the conference, attendees trade tips on the best ways to engage professors, or how to use disarming questions like Karma’s before delving into political topics. A common concern is ensuring that the movement’s vision outlasts the typical student’s four-year college career. As the focus shifts toward networking, the excitement in the room is still palpable.

“Not until coming here did I even understand the extent to which this is a movement,” says Zoe Isaac of Arizona State. “It’s happening, it’s big, and we want people there — and to be a part of it.”

Karma is optimistic about the group’s future. Most of the success stories lie on the personal level — like how Mimi Teixeira, a conservative from Massachusetts, and Geralyn Smith, a liberal from Louisiana, forged a close friendship through their participation. But it’s a start. If the next generation of leaders can learn to reach across the aisle, Karma says that’s a good sign.

As attendees depart, they stop to shake Karma’s hand and thank him. Students from Oregon promise to take him out for craft beers when he visits; a California sociology professor says she’ll call him soon for more discussion. He tears up while reflecting on the fact that it was his “simple and naïve idea” that brought all these people together.

“These conversations are what give me hope,” he says. “Our generation is called ‘coddled’ and ‘snowflakes’ and ‘little fascists’ and ‘lazy’ — but this restores my faith not just in our generation, but in our country.”

This summer, his involvement with BridgeUSA — as a student, at least — will draw to a close, when he leaves Notre Dame to take a job at the consulting firm McKinsey & Company. There he hopes to learn about capitalism from the inside.

“I want to be the person who can try to increase access to equal human dignity for as many people as possible,” he says. “I know that’s my goal. How I get there is unclear — but I recognize now that it’s a lifetime process.”

Tara Nieuwesteeg is a freelance writer based in Dallas.