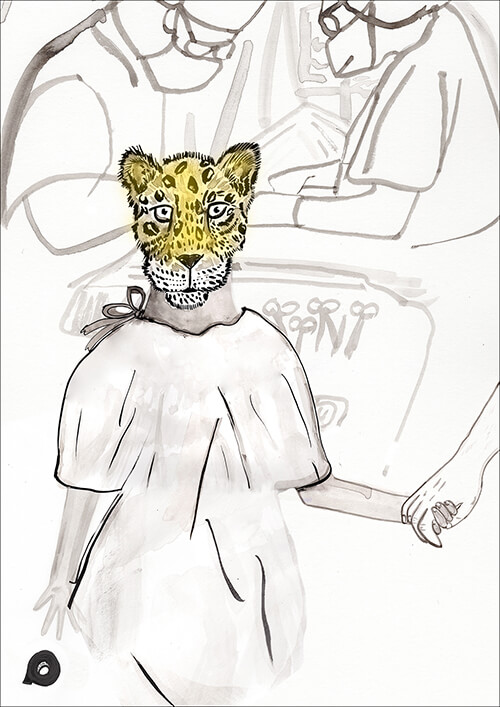

Illustration by Hayley Potter

Illustration by Hayley Potter

It is 6:30 a.m. and the sun is resting low in the east. We all speak in quiet tones as our bus pulls up to the hospital.

We see pickup trucks and old cars and small, green-and-white taxis idling endlessly along the dusty, cobbled street. A huddled line of shawl-covered mothers and wide-eyed children extends from the hospital’s weathered front door to the second turn around the corner. Several hundred people are waiting.

They wear sombreros or straw hats, the women in bulky jackets or dresses to preserve body heat in the foggy morning’s chill. We walk through the crowd scanning as many faces and expressions as we can absorb. We look for children with cleft lips, for burn-scarred necks and chins buried in chests, for swollen blood tumors (hemangiomas) and dark birthmarks (nevi), for extra fingers and toes, for deformed hands, for scarred limbs. These are our patients. Our mission is to help them.

The tension, the stare resulting from hours of waiting, of planning, of getting on buses, of calculating the cost of travel to this clinic, is palpable in this group. A profound anticipation hovers behind the gentle smiles welcoming us as we make our way into the clinic stations to start screening patients. This is our first contact with them, and we’re excited.

Out of the crowd, some 250 or 300 indigent children, teenagers and adults will come to the operating room over the next four days, and a surgical procedure will correct a defect that some have suffered for many years. One child in particular catches my eye — a small boy of 8 or 9 with a strip of electrical tape shielding his upper lip.

My examination station consists of a small desk, a flashlight, tongue blades, examining gloves, liquid hand disinfectant and blank charts ready to be filled in with vital statistics and surgical plans. We arrange to see the youngest patients first so they do not go too long without taking anything by mouth.

I am working with a scheduling nurse, a local translator and an operating room nurse. We bring in each young patient with one or two family members and ask questions about the child. Many of these children have been screened by Mexican health authorities. We examine the problem and the medical history. We ask about previous surgeries and what the families want for their child.

Once we’ve made a decision, we book them for surgery. They are checked by a pediatrician, an anesthesiologist and a nurse coordinator. All is made ready for procedures that will, in no small way, change each child’s life — and we assign a surgery time. That’s when families know they’ve cleared the first hurdle and may continue toward the ultimate goal of surgical correction.

At midmorning I see him again. The boy with the electrical tape, holding onto his mother’s hand. He is now fifth in line. He stands ramrod straight in his tattered white shirt and threadbare blue jeans. His shoes are scuffed and dusty. He will not look at me, but keeps his head turned toward his mother’s puffy white-and-red skirt. He does not smile, but stares ahead. The neatly cut electrical tape stretches across his upper lip, just below his nose and into the vermilion border of his mouth.

I proceed with my screenings but look down the line periodically. The boy will not look at me. He will not smile, will not laugh. He is like a little soldier ready for battle. His eyes are open and dry. There is no conversation between him and his mother.

The line moves slowly. When I get to the boy, I stand up from my desk and go to greet him and his mother. I shake their hands and ask the mother to sit next to me, and to have the boy stand before me. I am seated, and he stands facing me but looking over my shoulder. I ask his name. He replies in a soft, halting voice, “Juan.” He looks toward his mother, but never changes his determined look.

I cautiously ask about the electrical tape, and his mother answers quickly, trying not to call too much attention to it. She says he has been doing this for the past three or four months. Children at school talked about his cleft lip, she says, and he thought he could hide it with the tape. He asked her once if the tape could heal the lip and make it grow together.

She bows her head and looks away. Juan stares silently ahead.

It is interesting that some of these children have only a cleft lip defect with an intact palate. Juan’s speech is perfect, but he is not used to talking a lot because it calls attention to his deformity. What a hard way to grow up, I think. Juan has enough problems without this. It is not fair, but it is life.

The boy will not look at me. He will not smile, will not laugh. He is like a little soldier ready for battle.

I explain to Juan that we will fix his lip in a 30- or 40-minute operation. The stitches will dissolve in a few days. At first, the scar will be thick, red and swollen, but in four or five months, it will smooth out, and he will no longer need his electrical tape. He nods and looks to the floor.

Juan and his mother are directed to the anesthesia screening station and to the pre-surgical construction area. Straight, erect and looking forward, Juan takes his mother’s hand. His mother holds his medical records in her other hand, and I imagine how she might feel knowing that Juan will finally get his lip repaired, and he will be able to forget the teasing and the shame — and the electrical tape.

We start our operating program the next morning. I look at the schedule and see that Juan is my sixth case. I think about how brave and determined he is to get his lip fixed.

The fifth case finishes early and I go out to see him. His mother sits at the end of a long bench. Next to her, standing at attention and already dressed in his surgical gown, is a very somber little Juan staring off into the distance. I greet his mother and shake Juan’s hand. He has the look of a man condemned to death, ready to endure the unknown.

I try to reassure him that we will take good care of him and make sure that he has no pain. I do not know if he understands me, but I notice a small trembling in his chin and lower lip. He looks up at the ceiling with his eyes wide open so as not to display any tears.

Juan’s mother hugs and kisses him. He takes my hand, and I lead him to the operating theater, where surgeries are underway on the other two tables. The procedure is to allay anxieties by standing in front of patients so they do not see the other surgeries. Juan walks through the room deliberately, with just the slightest hesitation. He jumps up on the operating table, as brave as any grown man I have seen. He lies down and scarcely grimaces when the anesthesiologist places the mask over his nose and mouth.

We talk to our patients in low, soothing tones while the anesthesiologist turns on the anesthetic gases. Juan will not look into my eyes, but I tell him he is doing just fine, that he will be OK. His courage is evident as he tightens and furrows his eyebrows. I did not know him before yesterday, but I am so proud of him as he marches into the surgical battle.

The anesthesia deepens as Juan breathes in the gases. His eyes begin to fade and I can see he is hiding the deepest fears an 8-year-old boy could possess. Two enormous tears well up in the conjunctival recesses of his eyes, spill onto his cheeks and stream down to his ears. Poor Juan had not wanted to show how scared he really is, but the anesthetic liberated these feelings, and he is crying like we all need to do at such times.

Cleft-lip repair is a delicate procedure but usually has few complications. Within an hour, I think, all Juan’s anxieties, his shame and fear will be alleviated. This is the spirit of our mission, and here is the moment of truth. This is why we look forward to helping these children, time and time again.

After Juan is intubated and washed with the surgical prep, I mark his lip and inject a local anesthetic. We talk about Juan’s bravery, how none of us would have a fraction of his courage. The surgery goes very well, and 35 minutes later, we are wheeling Juan into the recovery room. In another 20 minutes, he will wake up and be on his way to a step-down bed.

Juan recovers very well. He has no nausea, very little discomfort and minimal swelling. I do not see him again until my rounds at the aftercare facility. He and his mother are sitting on a bed, and she is reading a book to him. About 30 mothers sit with their children in this one large room with beds lined up as in a Civil War hospital dormitory. What a sight to see — all these children spending the night together like a huge slumber party, mothers and children comforting each other.

The next day after a medical check, they pack up, receive medications and instructions, and go home. Follow-up with these patients will be at a government clinic or the hospital.

I’ve been on about 35 medical missions and met many children like Juan. Each child has a unique and touching story. Some will come back to see us on later missions, some won’t. Sometimes I wonder how these children are doing. Do they need a scar revision? Do they need a secondary procedure? Are they doing well in school? Is their social integration what we hoped it would be?

I’ve never seen Juan again, but I know that a trial like his often forges a stronger person. Sometimes the physical change does not produce the psychosocial metamorphosis we want. But change always occurs. I know Juan will never need electrical tape again and, when I think about him, I’ll bet he is doing just fine. A brave little boy like him would have to be.

Thomas Vecchione is a plastic surgeon in San Diego and a founding member of MOST, the Mercy Outreach Surgical Team, which has helped more than 10,000 patients in central and southern Mexico over the last 40 years.