Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

Photography by Matt Cashore ’94

The fall semester of 2020 was the stuff of future history books, never to be forgotten by this generation of Notre Dame students and employees. Normal campus routine was upended and replaced with strict rules designed to protect the community from the spread of the coronavirus.

Students spent the semester mostly outdoors or in their dorm rooms, heeding reminders to stay at least six feet away from others. Those who disobeyed the health protocols faced disciplinary action. By design, the stands in Notre Dame Stadium were more than 80 percent empty during football games.

During the pandemic, Notre Dame had a different look and feel: more distant and mostly quiet. Students attended classes in classrooms and other venues reconfigured to allow for social distancing. Everyone wore face masks — even joggers looping around the campus lakes. And with public lectures shifted online and all performing arts events canceled, few visitors appeared on the quads.

The new routine included daily mandatory online health checks. Bans on visitors in residence halls. Warnings to avoid parties, bars, restaurants and private social gatherings that would draw crowds or didn’t include antivirus precautions.

The University’s plan was designed to slow the spread of COVID-19, which by the end of the semester had infected more than 57 million people worldwide. In the United States by then, there were more than 11.7 million confirmed cases and 253,000 deaths.

Notre Dame altered its academic calendar in its effort to limit cases. The autumn semester began August 10, two weeks earlier than originally scheduled. Fall break was canceled, and final exams ended six days before Thanksgiving.

Social life and recreational activities moved outdoors. The University created a seating area on the Hesburgh Library quad with Adirondack chairs, fire pits, hanging lights and a stage for entertainment. Dubbed the Library Lawn, it immediately became a popular gathering place for studying and socializing.

Meals were served carryout style, with students eating in large tents, picnicking on the grass or dining in their dorm rooms. The dining halls opened for interior seating in October, with transparent panels installed across the tables to reduce the potential for virus transmission, then closed again by early November out of concern that indoor interaction was contributing to rising case numbers.

Some residence hall Masses moved outside or to lecture halls to allow more space between worshippers. The sign of peace was replaced with a hand wave, the “peace” hand signal or a quick elbow bump. The Basilica of the Sacred Heart limited the number of congregants and required reservations to attend Christmas Masses.

University leaders made efforts to cheer the anxious student body, including a September 24 music festival in the stadium. It featured free refreshments from food trucks and performances by 500 student vocalists and musicians, an opportunity to sing that many hadn’t expected to have this school year.

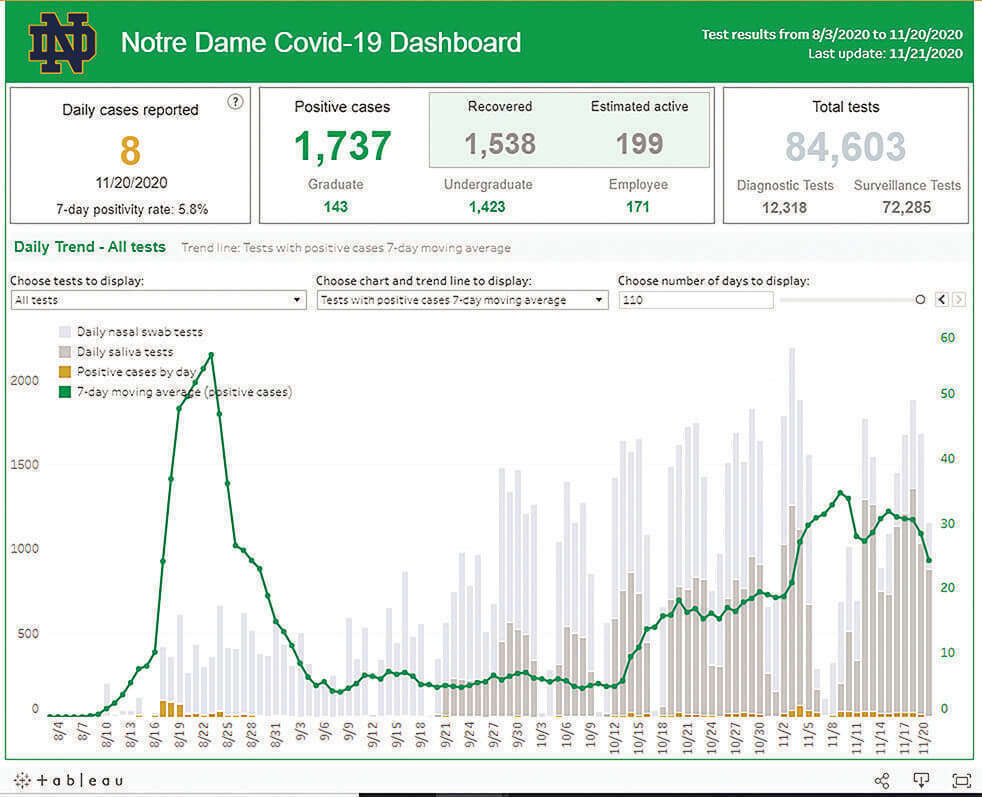

Each day students and employees checked the latest campus virus figures at here.nd.edu. The “HERE” dashboard reported such data as how many people on campus had tested positive the previous day, the seven-day positivity rate and the numbers of active campus cases and of individuals who had recovered.

Those who tested positive were isolated in apartments or hotel rooms, attended classes virtually and had meals delivered to them. Roommates and others identified via contact tracing were placed in quarantine.

“This has been the hardest year academically for me, and it’s not just classes. It’s a weird year to be in college,” says senior Gretchen Andreasen, who entered quarantine on November 9 after spending time with a friend who tested positive for COVID-19 the next day. Andreasen tested positive a couple days later, suffering symptoms including a stuffy head and a mild sore throat.

She remained isolated for 12 days, through final exams. Cleared to leave November 21, she made a quick visit to her dorm to gather her belongings, then drove home to Madison, Indiana.

The fall semester “was a lot harder in ways I wasn’t expecting. I had to relearn how to study,” Andreasen says. Before the virus hit, she often worked in small groups. When the pandemic made that all but impossible, she studied alone in her single room. “It became my work space, my living space and my eating space,” she says. “But I was definitely glad to be on campus.”

Approximately 138 of Notre Dame’s international undergraduates — nearly 30 percent of that cohort — weren’t able to make it to campus for the semester because of the global suspension of visa processing and U.S. entry restrictions. In response, the University launched an initiative to connect these students to campus resources. A reported 71 of them continued their studies virtually or at other institutions abroad, while others took a deferral or a leave of absence.

Senior Yanlin “Elaine” Chen was studying at Oxford last March when Notre Dame shut down its overseas programs and shifted all classes online. Chen flew to her family home in Shanghai. Travel restrictions prevented her from returning to Notre Dame in the fall. She took a leave of absence and hopes to return for the spring semester, although it’s unclear whether that will be possible.

“While I recognize that ND has made a significant amount of effort to ensure in-person learning, safety on campus is still a major concern for me, given the number of infections I saw on the [HERE] website,” Chen says. She spent her gap semester working an internship at a publishing house, learning to drive and preparing for the GRE graduate school entrance exam.

Chen is sad she won’t graduate in May with the Class of 2021. “It definitely disappointed me, especially considering that I may not be able to see my senior friends on campus upon my return, whom I missed a lot during my study abroad,” she says.

In October, officials moved the COVID-19 testing site they had set up in the stadium last summer into the north dome of the Joyce Center. The site added saliva-based testing and ramped up the number of employees called in for surveillance testing. It became a smooth-running operation, with test results generally provided the next day.

In addition to testing, other decisions helped to keep numbers relatively low. The University moved to online-only classes for two weeks in late August when the campus positivity rate soared to nearly 16 percent. Once in-person classes resumed, the number of new cases remained relatively low through September.

Then, mirroring the trend in Indiana and across the nation, cases started climbing in October. Administrators traced many new infections to larger parties held on the weekend of the October 10 Florida State football game. The University tightened restrictions, limiting informal outdoor gatherings to no more than 10 people.

Collectively the changes to campus life and academics posed challenges for students and faculty. “It was kind of a juggling act. It was hard to challenge the students equally,” physics professor Zoltán Toroczkai says of his graduate-level math course for physics majors. Some of his 17 students were in the classroom and others participated via video conferencing technology.

Professors like Toroczkai had more details to remember before each class, such as bringing a mask, a laptop and live-streaming equipment: In his case, a sloped ceiling in the lecture hall blocked an installed camera, so Toroczkai brought his own camera and tripod and set them up before each class to provide online students a clear view. Glitches with the audio or video meant class couldn’t proceed.

“I could tell the students were struggling. It was a constantly stressful situation,” he says. To help his students, he eased up a bit on the homework load and the difficulty of the problems.

He takes the threat of COVID-19 seriously. “It’s like Russian roulette,” Toroczkai says, striking down some people and causing no symptoms in others. Still, the semester was memorable and rewarding in some ways. “When you go into hardship with a group of people,” he says, “you come out with a sense of satisfaction.”

On October 2, the University announced that its president, Rev. John I. Jenkins, CSC, ’76, ’78M.A. had tested positive for the virus. The news came six days after Jenkins was seen maskless on national television, shaking hands at the crowded White House event at which President Donald Trump introduced Judge Amy Coney Barrett ’97J.D. as his nominee to fill a Supreme Court vacancy.

Jenkins was among more than a dozen University employees — most of them law professors, plus some spouses — who attended the Rose Garden gathering. Many from the University contingent appeared without masks in video and photos from the ceremony and inside the White House. At least a dozen people who attended tested positive within a few days, including Jenkins and Trump.

Jenkins and the others faced criticism from some colleagues and students for violating University protocols, including a proscription against nonessential travel. Jenkins self-isolated for two weeks and issued a written apology.

He wrote that it was important for him to attend the ceremony because Barrett is a Notre Dame alumna and was an active professor at the time. “I regret my error of judgment in not wearing a mask during the ceremony and by shaking hands with a number of people in the Rose Garden,” Jenkins wrote. “I failed to lead by example, at a time when I’ve asked everyone else in the Notre Dame community to do so. I especially regret my mistake in light of the sacrifices made on a daily basis by many, particularly our students, in adjusting their lives to observe our health protocols.”

Jenkins’ diagnosis drew national attention because he was among college presidents who had pushed aggressively last spring for campus reopenings in the fall. He had declared that convening Notre Dame for in-person classes was safe and “worth the risk.”

The Student Senate passed a resolution formally disapproving of Jenkins’ violations of the University’s COVID precautions. The Faculty Senate, in a 29-13 vote, adopted a “resolution of disappointment” regarding Jenkins’ actions, while also accepting his apology.

The football season went forward, but not without dramatic changes to game day traditions: No pep rallies, tailgating, band concerts on the steps of Bond Hall or player walks through ranks of cheering fans.

The Fighting Irish played the 2020 season as a temporary member of the Atlantic Coast Conference. Notre Dame, Saint Mary’s and Holy Cross College students were able to purchase tickets and attend home games. Faculty and staff could also buy tickets, but attendance was limited to no more than 20 percent of stadium capacity, about 15,525 fans per game.

Ushers were assigned to enforce face mask adherence among fans. A “physical distance camera” on the stadium videoboard displayed images of fans who were inching too close together. The Notre Dame Band and cheerleaders weren’t permitted on the field, performing instead socially distanced and in the stands.

“It was a surreal experience,” junior Grace Scheidler said after the September 12 season opener, a 27-13 Irish victory over Duke. Students sang the “Notre Dame Victory March” and other songs and did the traditional arm motion during the “1812 Overture” at the start of the fourth quarter. “It felt like muscle memory, doing all the usual things, but spread out and with our face masks on,” Scheidler said.

Seven Irish players sat out the September 19 game against South Florida after four players tested positive and six others were placed in quarantine. The next game on the schedule, at Wake Forest, was postponed to December 12 after seven additional players tested positive. (That game was later canceled.) By mid-November at least 55 games involving Division I football teams had been canceled or postponed for reasons related to COVID-19.

Students with tickets to the November 7 Clemson game were required to take COVID-19 tests, and those who didn’t show up for testing had their tickets canceled. That night game was the highlight of the 2020 home season, played before a mostly student crowd of 11,011. When the Irish won the game 47-40 in double overtime, thousands rushed the field, a celebration broadcast live on national television. The last time the Irish had downed a No. 1 team at home was in 1993, when Notre Dame beat Florida State 31-24.

Many cheering fans kept their masks on but pushed close together and surrounded the players and coaches, raising concern about spreading the virus less than two weeks before the end of the semester. The scene drew criticism in the national media and on social media. Photos of some large off-campus student parties that weekend also showed up online.

The next day, Jenkins reminded students about the University’s plans — announced before the Clemson game — requiring them to take a COVID-19 exit test by November 21 and before going home for winter break. “As exciting as last night’s victory against Clemson was, it was very disappointing to see evidence of widespread disregard of our health protocols at many gatherings over the weekend,” the priest wrote.

Students who ignored the exit-testing mandate or who left town before receiving their results faced tough penalties including a registration hold. Violators would not be able to enroll, register for spring classes or receive a transcript. As the semester drew to a close, administrators reiterated the zero-tolerance policy for gatherings that violated campus COVID-19 protocols, warning that those who disobeyed faced “severe sanctions.”

Daily case numbers climbed after Halloween, possibly driven by parties and the Clemson victory celebrations, but went nowhere near the double-digit rates seen during the August spike. The seven-day positivity rate reached 4.1 percent on the day of the Clemson game and hit a second peak of 7.9 percent 10 days after the game.

Some students who tested positive near semester’s end remained in isolation in South Bend through Thanksgiving. COVID-positive students who sought to leave before the mandatory isolation period ended had to request permission. They couldn’t fly and had to be accompanied by another driver, and the University notified local health departments at their destinations that they would be receiving confirmed COVID-positive individuals in their areas. Family members in contact with those students were advised to quarantine for 14 days.

The pandemic, health protocols and compressed academic calendar aggravated already serious problems with student depression and stress. In October, Provost Marie Lynn Miranda notified faculty of a University survey that found that more than 41 percent of students fell into categories of serious or moderate distress on a depression rating scale. Roughly one quarter of student respondents reported feeling socially disconnected or said they were having trouble concentrating. The University monitored signs of emotional health and well-being and made mental health counseling available.

Miranda thanked faculty for their “Herculean efforts and compassionate approaches” to helping students during the unusual semester. She encouraged professors to adopt creative ways to achieve course objectives while reducing student anxiety and workloads, such as dropping a low grade, allowing tests to be retaken, adding light moments in online classes, canceling class for a day or eliminating comprehensive final exams.

Students petitioned for the right to forgo course grades and instead be provided a “pass or no credit” option, as had been granted undergraduates in the spring. Administrators decided against renewing that policy for fall grading.

Pam Butler, an assistant teaching professor of gender studies, presented her fall courses online because she is immunocompromised. She checked in often with her students to ask how they were doing. “They were struggling,” she says, noting many consistently used words like “overwhelmed” and “overloaded.”

Butler canceled a few assignments and redirected her students to work in small groups on projects. Even though they were “meeting” virtually online, the students had the chance to share their thoughts and concerns — and their common humanity.

As it became clear the pandemic would continue through winter, the University made further changes to the academic calendar to lessen student and employee time on campus. The spring semester will begin February 3 and end May 19 with no week off for spring break, but a few minibreaks now appear on the schedule. Study abroad programs remain canceled.

The changes created an extended winter break of 10 weeks. Students have the option of participating in a “winter session” during January in the form of online courses, virtual internships, research or community service opportunities.

By the final day of the fall semester, the University had conducted more than 84,000 COVID-19 screenings and reported a total of 1,737 coronavirus cases: 1,423 among undergraduates, 171 among employees and 143 among graduate students. No deaths due to coronavirus infections were reported.

A few days before Thanksgiving, students headed home. However one defines success, this very strange semester was brought to completion, and both faculty and administrators were glad to breathe a little more easily as more than 12,400 students temporarily left their care.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.