If you take courses in Notre Dame’s department of art history, you can learn a lot about the art of ancient Greece and Rome, medieval France and the contemporary United States. But until recently, you couldn’t learn much at all about the art of China or Japan.

This semester, the University launched its first-ever course in Asian art history — and its instructor says the new offering is but a harbinger of the greater change to come.

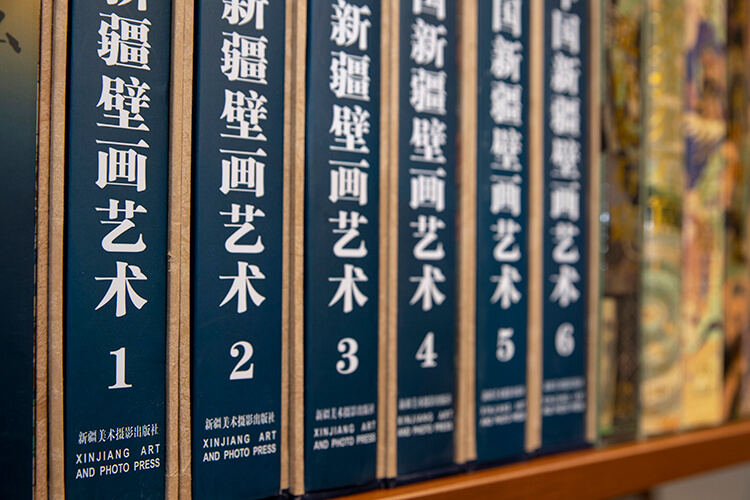

Art books in Dr. Fletcher Coleman's office. Photos by Barbara Johnston

Art books in Dr. Fletcher Coleman's office. Photos by Barbara Johnston

“Notre Dame has a long history with teaching and understanding art history, particularly rooted in the Western tradition,” says Fletcher Coleman, a visiting assistant professor in the art history department and the Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies who teaches the course. “But I think in recent years there’s been a push to expand into global art history in the department here. The department, as it moves toward the future and looks to expand, is really looking toward the global world.”

Like much of society — think the #OscarsSoWhite debacle, or the law firms and congressional intern classes that have been lambasted online for their lack of visible minorities — the field of art history is in the midst of a diversity renaissance. ARHI 20703: Introduction to the Arts of Asia is one of Notre Dame’s efforts to join in.

Coleman attributes much of the rising interest in Asian art in particular to simple economics, joking that, as an undergrad in the mid-2000s, he was among the last group of college students to study Mandarin out of pure cultural interest rather than a desire for economic gain. Art historians, he claims — like professors of language or business — have followed the money in recent decades as countries like China and Japan have become increasingly significant economic powers.

In support of that theory, several of the 27 students in ARHI 20703 are business majors fulfilling their fine arts requirement with a course that’s relevant to their career aspirations. But many more are art and art history students or just curious enrollees from other departments, whose reasons for signing up vary widely.

Some, like sophomore art history major Meg Burns, were interested in the diversity that the class represents.

“The primary reason I signed up,” Burns says, “was to try and expand my knowledge of art history beyond the traditional Western-centric canon.”

Junior Laura Richter expressed a similar motivation for enrolling and added another: Coleman’s melding of art-making with art-examining.

“Being particularly fascinated by artistic materials and techniques myself,” she says, “I was excited to see Professor Coleman’s course promised hands-on activities.”

Each unit of Arts of Asia — from Chinese woodblock printing to East Asian ink painting — features at least one hands-on class session, in which students get to experiment with the techniques they’re learning about. On the day I visited in mid-February, the art project du jour was calligraphy. I joined in with the students, and even without understanding the characters I was copying, I had a great time. For students who’ve been learning the history of the techniques, there’s little doubt that it helps enormously with their appreciation for the material.

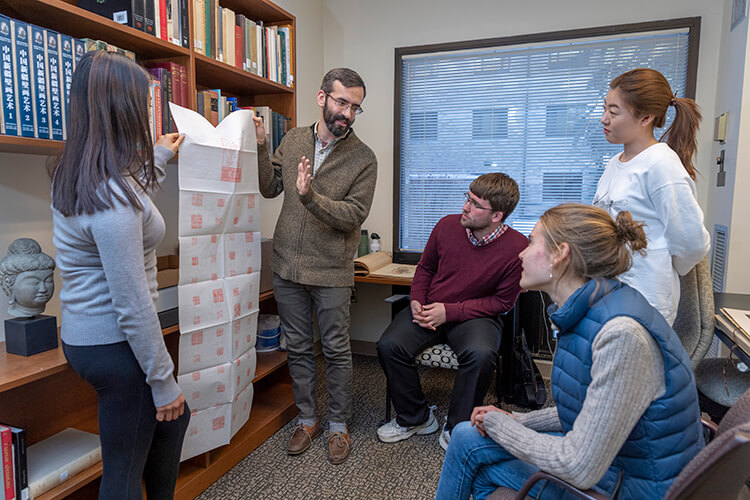

Coleman and students at work in his office

Coleman and students at work in his office

“You don’t have to be an expert in studio art as an art historian,” Coleman says, “but you really can, I think, inform your work pretty heavily if you have some sort of foundational understanding of artistic practice.”

This incorporation of hands-on practice, known as technical art history, is both a specialty of Coleman’s and, he says, a growing trend.

“It used to be common actually, in art history departments in the early 20th century, that you were joined together with the fine arts departments under one roof as a school of art,” he says. “That’s less common now, as the disciplines sort of moved their separate ways in the late 20th century. [But] I’ve found in recent years there’s a movement to bring back the study together with one another.”

At Notre Dame, the two disciplines never separated and have instead long shared an academic home in the Department of Art, Art History and Design. That makes Our Lady’s University a perfect fit for a class like Coleman’s — and for a scholar of this hybridized style of art history.

The future of this Cool Class is somewhat uncertain since its instructor is, for now, still just “visiting.” But regardless of whether the exact class lives on after this spring, its pedagogy and its focus on non-Western art are likely to leave a legacy that lasts far longer than one semester.

As the University becomes increasingly international and its students demand ever more diversity in their studies, it’s safe to say that Introduction to the Arts of Asia is truly just that: an introduction.

- Cool Classes

- Irish-American Tap Dance

- One's Life Story

- American Political Journalism

- Summer Abroad

- Culture, Conflict, and Commemoration

- Moreau First-Year Experience

- Beginning Furniture

- The Chemistry of Fermentation

- Rethinking Crime and Justice

- Playing Shakespeare

- The Arts of Asia

The Liu Institute is quick to point out that, long before there were eager teenagers taking Mandarin to further their job prospects, Notre Dame had a vested interest in Asia. Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, made his first visit to China in 1979, and said upon his return that “anything relating to a fourth of humanity must be important, however much it may differ from one’s own version and vision of what the world and mankind are and might be.”

Four decades after Hesburgh’s maiden Eastern voyage, the University he once led has three offices in Asia and an entire institute dedicated the study of Earth’s largest continent. ARHI 20703 may be Notre Dame’s first class devoted to Asian art history, but it’s unlikely to be its last.

Hesburgh kept his office on the 13th floor of his namesake library decorated with a number of Asian artworks, and the University president often wrote and spoke of his fondness for the the continent and its art. Long before there were eager teenagers taking Mandarin because it helped their career prospects, Hesburgh had an abiding interest in Asia, and a desire to apply that interest at Notre Dame.

“Anything relating to a fourth of humanity must be important,” he said after his first visit to China in 1979, “however much it may differ from one’s own version and vision of what the world and mankind are and might be.”

Four decades later, the University Hesburgh once led has an institute for Asian studies; offices in Beijing, Hong Kong and Mumbai; and, now, an entire class dedicated to the Asian art that he so loved to collect. As the University becomes increasingly international and its students demand ever more diversity in their studies, it’s safe to say that Introduction to the Arts of Asia truly is just the beginning.

Sarah Cahalan is an associate editor of this magazine.