Lozada’s act of “transcendent masochism” helps us better understand Donald Trump’s America. Photo by Carrie Gates

Lozada’s act of “transcendent masochism” helps us better understand Donald Trump’s America. Photo by Carrie Gates

My Uncle Jonas died in April of complications from COVID-19 that swept through his long-term care facility. A true-blue Massachusetts liberal, Jonas ended all our conversations since the election of Donald Trump with a question: How did we get here?

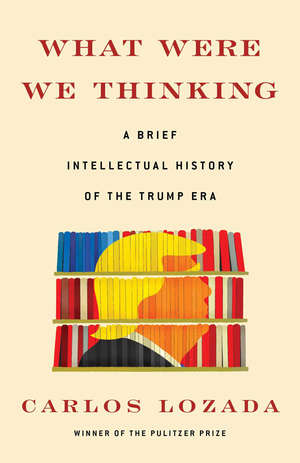

My neighbor, Carlos Lozada ’93, has produced one of the most comprehensive answers with his new book, What Were We Thinking: A Brief Intellectual History of the Trump Era. I only wish Jonas were here to read it.

A month after Trump descended the escalator into the lobby of Trump Tower, launching his presidential bid, Lozada had an idea. He had recently become the Washington Post’s nonfiction book critic. What if he offered to binge-read a selection of Trump’s ghostwritten books dating back to the 1980s and share whatever he learned with his readers? The editor approved, but urged deliberate speed. It wasn’t clear in July 2015 whether America’s fascination for all things Trump would be long lasting.

After Trump won the presidency, Lozada’s project expanded. His consumption of Trump-related books kept intensifying along with America’s seeming insatiable appetite to either lionize or vilify the real estate developer-cum-reality show star-cum-leader of the free world.

Five years later, after reading more than 150 books about Trump and the era, the Pulitzer Prize-winning critic has turned what political author Joe Klein called an act of “transcendent masochism” into his first book.

Imagine stuffing the full spectrum of Trump genres into an immersion blender — from the bombshell-laden tell-alls to books that hardly mention the president at all but evoke his America. In What Were We Thinking, Lozada distinguishes books that truly explain the era from those that might be considered literary fast food, momentarily titillating with outrageous anecdotes but leaving you hungry for what it really means.

Having spent my career as a Washington journalist, it’s no surprise that Chapter 5, “True Enough,” speaks directly to me. A journalist’s mission to strive for accuracy has made the past four years dispiriting and exhausting, far beyond the usual challenge of sifting through political spin for the facts. As Lozada writes, “Trump would love to exert power over the truth itself. He has settled for power over us.”

Lozada, a Notre Dame adjunct professor of political journalism, examined dozens of accounts of how Trump acquired such power despite no political experience and a checkered reputation in business. That’s what stumped Jonas: how? Despite four decades in Washington newsrooms, I was stymied to offer a satisfying explanation, so I put the question to Lozada.

“Part of the reason it happened is that so many people thought it couldn’t,” he said. “We treated his 2016 campaign like a publicity stunt, giving it both more attention and less seriousness than it deserved. Major American institutions — in politics, in the press, in the tech world — simply assumed Hillary Clinton would win, and even lots of voters did, too. In hindsight, it was a pretty cavalier way to treat our democracy.

“Within the Republican Party, the traditional gatekeepers and party leaders seemed to think they could eke out one more mainstream nominee without alienating the more extreme forces in the Republican base — but once they realized they couldn’t, simply made their peace with the situation, deciding that the tax cuts and Supreme Court nominees and deregulation were worth it.

“Finally, many of the books I read tried to understand the motives of Trump supporters among the white working class, and usually boiled it down to one of two culprits: either economic anxiety or cultural prejudice. But one of the most insightful books on the white working class that I read, We’re Still Here by Jennifer Silva, emphasized how, rather that pushing them to support one candidate or another, the struggles of the white working class often led them to think there was no room in the political system for them at all, no one who would listen. In that mindset, it becomes easier to vote for someone who promises to tear it all down. Silva wrote her book during the 2016 campaign and election, and when she wore her “I Voted” sticker, some of her interview subjects mocked her for being naïve enough to think that the system would be responsive to her vote, to her desires. It’s a scene I can’t forget, and a reminder that the best books I read about the Trump era are barely about Trump at all.”

If only Jonas would have had the benefit of Lozada’s insight. I’ve promised myself when COVID restrictions lift and I can visit Jonas’ grave for the first time, I’ll not only tell him who won the election, but finally offer a better explanation of what we were thinking and how we got here.

Richard L. Harris has been a Washington journalist for more than 40 years, including as senior producer of ABC’s Nightline with Ted Koppel and as the producer of NPR’s All Things Considered.