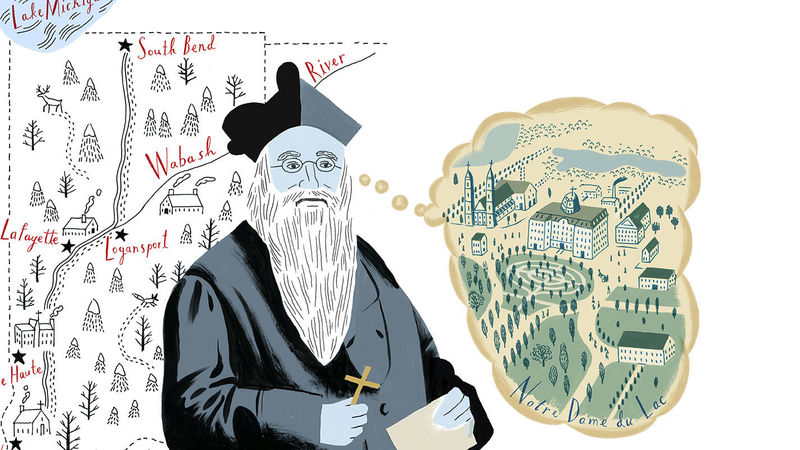

Bishop Simon-Gabriel Bruté de Remur visited France in 1836 to petition and recruit. He needed money and men for his nascent missionary diocese in the United States that covered all of Indiana and part of Illinois, a 50,000-square-mile frontier of the faith.

Among the stops on Bruté’s tour was the St. Vincent Seminary in Le Mans. Most of the seminarians there, including 21-year-old Edouard-Frédéric Sorin, likely had never heard of the distant territories he represented.

- Celebrating 175

- The Notre Dame Trail will retrace the steps of founder Rev. Edward F. Sorin, CSC, from Vincennes to South Bend, August 13-26, 2017. The final day will include walking the last three miles, Mass and campus celebration. For more information go to trail.nd.edu.

Bruté’s charms in selling the place to his audiences, though ample and productive, were not of the chamber of commerce variety. He was 57 then but seemed much older, missing most of his teeth and possessing only halting command of both his native French, forgotten overseas, and the English of his home for the previous 25 years. Still, as had been the case all his life, people were taken with him.

Sorin biographer Rev. Marvin R. O’Connell describes Bruté as “a curious combination of prayerful ascetic and unpredictable eccentric,” but he exuded simplicity and courtesy. “A perpetual half-smile playing across his lips,” the bishop radiated decency that transcended what he lacked in political charisma. He attracted powerful friends. Napoleon, for example, had nice things to say.

Born to wealth in 1779, Bruté became a doctor, then a priest, immigrating to the United States in 1810, where he worked with or taught many early American leaders of the Catholic Church. His closest confidant was Elizabeth Ann Seton, whose Sisters of Charity gave $245 in start-up capital that Bruté carried west to Indiana when he became Bishop of Vincennes.

Whatever his personal virtues, the reserved bibliophile did not inspire confidence among colleagues that he would be up to an administrative job so big in landscape and scope. But the warm light within him, and the missionary moths drawn to his flickering flame, put the diocese on a path toward stability.

From Le Mans and elsewhere in France, Bruté gathered some of the material he would need for the job, including a priest named Célestine de la Hailandière. He would become Bruté’s successor and an antagonist in the story that led to the founding of Notre Dame.

Sorin, still two years from ordination, was not yet able to enlist for the foreign mission but, O’Connell writes, Bruté demonstrated “a priestly dedication and a spirit of adventure that lit up the young heart” of the ambitious seminarian.

Sorin shared Bruté’s characteristics and also possessed the vision and self-assurance to build on the unlikely bishop’s foundation when his time came.

The boy who played priest

In Ahuillé, a village in western France, the Sorin family was among the elite. Not wealthy, but comfortable and of distinguished status because Julien Sorin de la Gaulterie owned the modest land he farmed. They were, among the French of their time and place, notables. What’s known of young Edouard’s traits were attributable to his place in the society he was born into in 1814 and foreshadowed the man he became.

O’Connell: “The posture of command he so readily assumed during his career, his self-confidence, his willingness to take up any challenge and embark on any adventure, and, less attractively, his propensity to ride rough shod over opponents — all these characteristics of leadership reflect to some degree the position of relative privilege in which Edouard Sorin was reared.”

- God, Country, Notre Dame et cetera

- 175 and Counting

- En Route

- The Passing of Ancestral Lands

- The Stationmaster

- The Littlest Domers

- The original home-grown do-it-yourself meal plan

- Gettysburg, 1863

- Washington Hall

- Commencements through history

- Cartier Athletic Field

- The old ND&W

- As ND as football, Mother’s Day and community service

- Notre Dame vs. Army: The rivalry that shaped college football

- Bound volumes, illicit lit

- Mock political conventions

- The Collegiate Jazz Festival

- When the Irish got their fight back

- The damnedest experience we ever had

- 40291

- It takes a University Village

Religious devotion was another reflection of his upbringing, and it made a particular impression on the seventh of the nine Sorin children. Family lore says Edouard crafted vestments out of paper and pretended to be a priest, offering Mass at a makeshift altar to other village children. His flight of imagination would have been relatively unremarkable in a region with a strong Catholic identity, except for the living memory of persecution and protection of the faith among the community’s elders.

At the end of the 18th century, some 3,000 priests were killed and tens of thousands more exiled in an “orgy of hatred and destruction” that accompanied the French Revolution. Julien Sorin and his wife, Marie Anne Louise Gresland de la Margalerie, risked their means, if not their lives, to offer their home as a shelter for priests.

Resistance in the provinces became legendary tales in the decades that followed. A man called “the Mustache” led the guerillas of his home district of Mayenne and the surrounding region. The stories Sorin heard as a boy established the primacy of religion to the cause of the Mustache and his men. The allied restoration of the French monarchy came to mean far less to the people of western villages like Sorin’s than Catholic faith, Catholic practice and, especially, the Catholic priesthood.

Although French clergy had lost much of the secular status they held before the revolution, their numbers and holy vigor began to grow in the decades after. “Few periods of modern French religious history,” Robert E. Burns writes in Being Catholic, Being American, “witnessed such an outburst of spiritual, intellectual, and organizational energies.”

Father Basile-Antoine Moreau was among the catalysts. Precocious among his fellow priests and tenacious in his attention to what he considered the regimented duties of faith, Moreau quickly rose to prominence, becoming a professor at the St. Vincent Seminary where had trained. Sorin, on his own accelerated path to a religious life from his mid-teens, would be among Moreau’s students in the 1830s.

The hollowed-out Church of post-revolutionary France needed a renaissance of religious instruction. In the Mayenne region where the Sorin family lived, 341 parochial schools were thriving in 1789. Within a decade, they were all gone.

Congregations and other Catholic associations sprang up around the country, dedicated to filling that gap. Among them were the Brothers of St. Joseph, which merged in 1837 with Moreau’s Auxiliary Priests of the Diocese of Le Mans, a marriage that begat the Congregation of Holy Cross. The congregation’s founding document “left no doubt as to who would be in charge” — Moreau, first and foremost, and priests above brothers in the institutional hierarchy.

France was hardly the only place that needed education-minded men to revive Catholic schools. Requests for help from around the world — from Algeria to Canada to Vincennes — reached Moreau. He felt inclined to comply, to enhance both the Catholic religion and his young congregation’s reputation. Moreau’s men, Sorin prominent among them, also were eager for the missionary opportunities.

In 1841, Moreau decided to send six Holy Cross brothers to the Vincennes diocese, now under Hailandière’s direction. Three teachers, a farmer, a tailor and a carpenter were chosen. According to the congregation’s hierarchical rules, a priest would need to lead their mission. This responsibility went to Sorin, who accepted it with effusive enthusiasm.

“The road to America,” he wrote to Hailandière at the news of his assignment, “is the road to heaven.” He went on to extol the miseries that he would have to endure over land and sea to reach distant Indiana in the Church’s service. “I look forward to sufferings over every kind, and I know ahead of time that the good Master will maintain his protection over me, which is all I aspire to . . . I have a great need to suffer!”

The journey ahead of him would go a long way toward satisfying his “hunger and thirst” for life’s unbearable burdens.

The road to heaven

After 20 hours on a stagecoach from Le Mans to the Normandy port of Le Havre, Sorin and the six Holy Cross brothers departed, clotted with 200 other steerage passengers aboard the Iowa, on Sunday, August 8, 1841.

The ship stood essentially still in the English Channel for about a week, but the waters bobbing underneath belied the absence of a breeze needed to propel them west. The passengers’ stomachs churned and heaved in the nauseating sway.

“Whoever has had experience of the sea,” Sorin wrote in his Chronicles of Notre Dame du Lac, “knows how it paralyzes and in a sense annihilates the physical and moral powers of even the most courageous.”

A sense of humor prevailed among the men even in the depths of debilitating illness. The queasy six (one brother was spared the malady at first, though his brethren later had to reciprocate the care that he had given them) joked with each other that mere seasickness was no test for their brave souls.

“Even when they were hardly able to stand or to raise their heads, they did not altogether lose that gayity which always accompanies a conscience at peace with itself,” Sorin wrote. “It was amusing to hear them ask one another, between the throes of those revolutions that were going on within them, whether they still thought the world big enough to bear any proportion to their courage.”

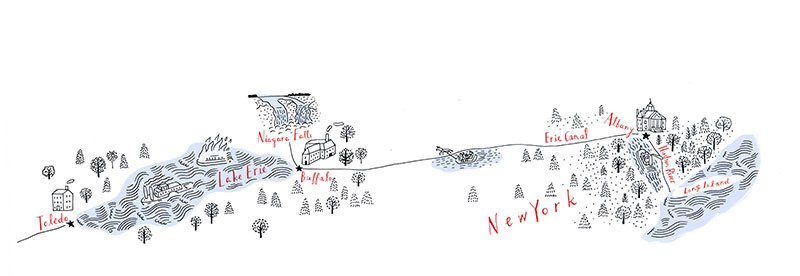

Once the Iowa reached open water, the men remained well and the voyage lasted only about four more weeks, a brisk 35 days in all from Le Havre to New York harbor. Sorin said Mass 11 times on the journey — and a funeral service for a 2-year-old German girl who died en route.

When the girl became ill, the Sisters aboard entreated her Protestant father to have her baptized. “After many fruitless pleadings,” Sorin wrote to Moreau, the man consented. “Two days later the new Christian went to take possession of the heritage that had just fallen to her.”

While her body rested on a plank, Sorin performed the funeral rite. Afterward the board was tipped upward at one end and, the priest wrote, “the little corpse slid gently off, and the next instant it was heard dropping into the sea; but the soul which had taken its departure was already in heaven.”

The Holy Cross men remembered the girl they called “little Mary” for years afterward, O’Connell writes, as “a Providential token . . . that in undertaking this perilous mission they were fulfilling God’s special designs.”

Only the usual discomforts of close quarters with dozens of strangers befell them the rest of the way to New York, where Sorin disembarked on September 13, 1841. He fell to the ground and “embraced” the soil upon arrival, but the journey to Vincennes would be weeks longer still and more diverting in scenery and anxiety than the Atlantic crossing.

They left New York City on a Hudson River paddleboat. Nature’s “prodigious grandeur” evident on its shores exceeded, in Sorin’s estimation, even the lovely Loire Valley. At Albany the next morning, they boarded a horse-drawn freight barge on the Erie Canal, bound for Buffalo at four miles an hour.

This relatively cheap mode of passage along the canal attracted a rough clientele. The Frenchmen in cassocks, who “performed unintelligible devotions” among themselves, were not of the usual crowd. As O’Connell put it, the Holy Cross men were “not only foreign but peculiar.”

Much of what they encountered seemed peculiar to them as well, particularly the forestry and farming practices, “a great negligence” Sorin intuited from what he saw. “I do not know whether they have ever uprooted a tree in America.”

A side excursion refocused his vision from the neglect of the earth to the splendor of creation. Sorin and the eldest brother rode by train to Niagara Falls and paid their 25 cents apiece to see the wonder of nature.

“We stopped for some time as if rendered immobile by astonishment,” Sorin wrote. “Then we dropped to our knees, and there amid the noise of the surge of the torrent, amid marvels so new to us, we adored the infinite power of the Creator of all things.”

Instead of scratching their names into a tree, as other visitors to the falls had done, they carved a cross as a mark of their visit. “That was our name and surname.”

They caught up with the rest of the traveling party in Buffalo for the steamboat ride over Lake Erie, after which they planned to rejoin the canal network across northwest Ohio into Indiana and on to Vincennes.

Six weeks earlier 175 people had been killed in a steamboat fire on the same Lake Erie route. With trepidation in their hearts, plus choppy waves churning their stomachs again, the three days to Toledo were another test of their endurance. But not as stern a test, in retrospect, as two tumultuous days that soon followed.

When the Holy Cross contingent, struggling to communicate with the Americans they encountered, finally reached the place where they expected to rejoin the canal, they discovered the fragmented project did not yet extend that far. They had to hire two carriages and four horses, in transactions conducted mostly in sign language, to ferry them through the forest over rutted, muddy paths. If there were paths at all.

“It was especially during this part of the journey . . . that they had occasion to remember the care heaven took of them,” Sorin wrote.

He certainly wouldn’t have attributed any protection to the earthly guidance of the men accompanying them. There were five in all — two brothers in charge, “veritable rogues, who made efforts to steal from us,” and three others with no apparent purpose to the trip and, as Sorin remarked, “completely without religion.” For fun, they fired their rifles into the woods at random.

Where trees had fallen, the guides had to blaze a way around and through the thick growth. Other times they had to navigate rain puddles, wheels halfway submerged, the carriage struggling as if through quicksand. Swollen streams that they had to cross flowed with such force that the currents carried them “into vast ponds where our horses went in up to their breasts.”

Even when they did find a clear path, it often appeared to Sorin, roiling with fear but stoic for his men’s sake, that only inches separated them from steep 60-to-80-foot descents into who knows where.

“At each ravine, at each mud hole,” Sorin wrote, “I muttered an Ave with my gaze fixed on the danger.”

They came to no serious harm. “A little tired, it is true, and all covered with mud,” but by time Sorin wrote those words, they were aboard a boat that carried them along a completed section of the Wabash and Erie Canal toward Vincennes.

About two months earlier they had left France. Debilitating illness and mortal danger were the harrowing price of entry into Sorin’s American heaven, the final leg covered on foot in the middle of the night. This “forced march across the sands” on the banks of the Wabash River brought them to the tower of the Cathedral of St. Francis Xavier on the morning of Sunday, October 10, 1841.

Hailandière received the Holy Cross men “like well-beloved children,” a sentiment that did not last much beyond the first blush of greeting.

A Le Mans man in Vincennes

In his letter from the boat reflecting on the “romantic” adventures that buffeted them through the Indiana woods, Sorin noted that the traveling party was “gathering the strength in order to sustain us for the rest of our trials.”

Vincennes and environs, still the rugged frontier, offered little in the way of creature comforts, to be sure. There, O’Connell writes, “the vows of poverty they swore as religious took on a radically new meaning.”

The cathedral was a “small, squat building,” the bishop’s residence likewise spare and simple, and those were among the few buildings in the surrounding wilderness. There was no place yet designated to house the new arrivals. But the biggest problems awaiting Sorin would be bureaucratic.

Hailandière’s authority over the Holy Cross men was a point of contention because Moreau also had a claim to jurisdiction over those of his congregation. The relationship between the two amounted to a long-distance tug-of-war for control of the men while deflecting responsibility to provide resources that neither had in abundance. Sorin, unaware of the tension until his arrival, found himself caught in the middle.

Hailandière needed the brothers Moreau sent from France to support the schools he planned across the diocese. As their superior, Sorin was not merely another priest to serve local Catholics but the highest-ranking congregation man in Vincennes. “An agent of Basile Moreau,” from Bishop Hailandière’s point of view.

Combine the fact that Hailandière “was a man utterly without tact” with Sorin’s stubborn commitment to his own positions and the circumstances were primed for conflict. Wherever he directed his loyalties, Sorin’s expansive (and expensive) ambitions likely would not have aligned with the bishop’s plans.

First, Hailandière had to decide where to put the men. He made a point of giving them a tour of potential sites. A settlement called Francisville did not appeal to Sorin, “though I cannot exactly tell you why.” Another option was St. Peter’s Mission, nearly 30 miles east of the Wabash River near the town of Washington, Indiana.

After a discussion, including fawning descriptions of the landscape, lasting late into the night, Sorin and another priest set off on horseback to see the 160-acre farm with a few aging buildings and small chapel. The site appealed to him, and he came to believe that’s where the bishop had intended to bivouac the Holy Cross missionaries all along.

The men set to work almost immediately. They established a novitiate that attracted a dozen men within a year, an amalgam of German, English and French speakers with little overlap, suggesting that communication must have been among their early obstacles.

In addition to the novitiate, a notice for a new boarding school at St. Peter’s was published before they had been in the diocese two weeks, historian Rev. Arthur Hope, CSC, notes in his book, Notre Dame: One Hundred Years. Quarterly tuition and board, “including washing and mending,” would be $18, payable in advance.

They would need that money up front. With little on hand, or on offer from the bishop or forthcoming from Moreau back in France, the “School for Young Men” they envisioned had scarce material to bring it to fruition.

“We are not mentioning the fact that we shall have to use the attic for a dormitory,” Sorin wrote to Moreau. “We don’t speak of the refectory; nothing has been said for the fact that the teachers will probably not understand their new pupils. Tell me, are we not men of faith?”

Sorin’s vision, O’Connell writes, sometimes “merged into fantasy.” Clear-headed assessments of the community’s material circumstances mingled in his mind with vivid dreams untethered to the restraints that encumbered them.

Lacking a working knowledge of the language or the land — an insubstantial harvest in 1842 exposed the latter — reality ultimately intruded on his wildest imaginings. “An experienced guide is needed,” Sorin wrote, “otherwise devotedness will wear itself out to little purpose.”

Even the devotedness Sorin and the Holy Cross men displayed worked against them at times. “The paranoid Hailandière” perceived them to be conspiring with the diocesan priests, who held their own grievances toward the bishop.

For his part, Hailandière resisted Sorin’s idea of a school — modeled after a French collège, or secondary school, not a university — because he had promised another Catholic congregation in Vincennes, the Eudists, that he would not infringe on their struggling institution nearby. Sorin countered that without their own St. Peter’s school, 30 miles away, the community struggling to establish itself there could not survive.

Testy letters between Sorin and Hailandière yielded the bishop’s offer, if the priest must remain so intent on opening his collège, of diocesan land known as Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs in northern Indiana near South Bend for the purpose. This would satisfy Sorin’s ambition to start a school and Hailandière’s obligation to the land’s donor, Father Stephen Badin, who had offered it to the Vincennes diocese with the stipulation that it be used for a “religious or charitable project.”

There was another benefit to the plan. “The prospect of separating themselves by a distance of more than two hundred miles,” O’Connell writes, “was more than welcome to both men.”

As a condition, Hailandière expected some Holy Cross staff to remain in the Vincennes region and continue to carry out the duties they had undertaken. Because of the congregation’s rules requiring a priest to act as superior, Sorin had a problem of how to extricate himself from that role in the fledgling community. He dispatched of it, O’Connell continues, “in the most high-handed and imprudent fashion: he named Father Étienne Chartier, a postulant of only a few weeks standing and a man he hardly knew, to act as director of those brothers to be left behind.”

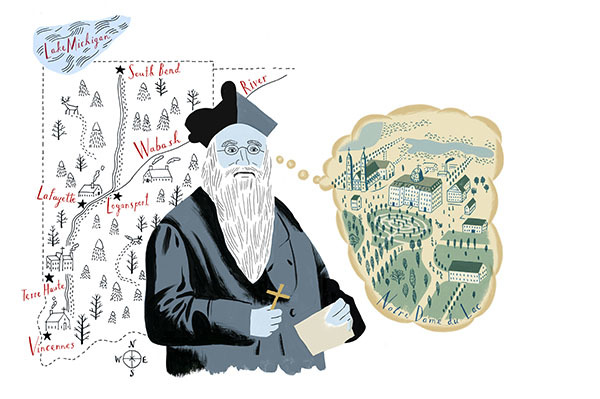

Sorin wanted out, whatever it took, even if it meant going through the administrative motions without even notifying Moreau, or actually trudging more than 250 miles in the snow to get to his school.

North to South Bend

“A true cold of Siberia” assaulted Sorin and the seven Holy Cross brothers who departed for South Bend in mid-November 1842 with their possessions loaded onto an oxcart. At Vincennes, the bishop provided them with horses and a wagon. Sorin and Hailandière later sparred over whether that was meant to be a loan or a gift and, at length, the horses were returned.

Illustrations by Curtis Parker

Illustrations by Curtis Parker

The bishop did provide them with $310 and a letter of credit for an additional $231 (“and twelve and one-half cents”) to be presented to a Mr. Coquillard of South Bend. “My hopes are enormous, as are my desires,” Hailandière said in his farewell letter.

The group made it less than eight miles in the arctic conditions on the first day of their journey, the snow and ice requiring them to take particular care with the animals. The impatient Sorin could not tolerate such a pace. Summoning four of the brothers, he set off in the horse and wagon ahead of the other three, who were left to labor along at the heavy oxcart’s slower speed.

The wagon broke down four times along the way, but in the end, the travelers managed to cover about 25 miles a day. Their path wound along the Wabash River up past Terre Haute, then turned eastward toward Lafayette and Logansport. From there, it was north to South Bend and the warmth — in hearth, food and welcome — of the Alexis Coquillard home.

November 26, 1842, has been accepted as the date, after 11 days en route, that Sorin and his accompanying brothers set foot on Coquillard’s snow-covered property.

“Père Sorin?” the South Bend fur trader asked, emerging from his house to greet the men whose arrival he had anticipated since receiving a letter from the bishop.

They were welcomed with great hospitality and a meal of hot soup and bread. Still impatient to reach Sainte-Marie-des-Lacs, Sorin waved away the insistence that the group should rest, asking to be shown the way immediately. Coquillard summoned his 17-year-old live-in nephew and namesake, young Alexis, to take the men north of town to the property Hailandière had ceded to them.

A trapper named Nicolas Charron lived in a shack on the land, where he had served as an interpreter between previous missionaries and the native people. Nearby stood a derelict log structure, a chapel and residence for the priests that preceded them there, now dark, cold and foreboding inside. Among their predecessors was a Father Louis DeSeille, who was buried beneath the floor near the altar, where Sorin knelt to say a prayer for him.

Ascending a ladder to a loft, the men found a place to sleep, but it required repair before it could be used. They would have to return, temporarily, to the Coquillard home until they could make theirs suitable.

The land outside, on the other hand, needed no improvement. Frozen and frosted with fresh snow, the lakes and the forested acres that surrounded them brought to Sorin’s mind “the spotless beauty of our august Lady whose name it bears.” The sweep of the land warmed their hearts and revived their fatigued spirits.

They explored their grand new inheritance and, “like children, came back fascinated with the marvelous beauties of our new home” that Sorin christened, still in Mary’s name but on his own terms, as Notre Dame du Lac.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.