From college buildings to courthouses and stately homes, the built environment of the South Bend area fascinated John W. Stamper, a Notre Dame architecture professor and associate dean.

In addition to teaching, Stamper spent a lifetime studying and documenting the architecture of the city and its nearby campuses. One result is a new book, City and Campus: An Architectural History of South Bend, Notre Dame, and Saint Mary’s, which examines the architecture and urban development of the region from the frontier days of the early 1800s through the 20th century.

The author, a longtime fixture in the School of Architecture, had nearly finished the book when he died in 2022 at age 71. After his death, colleagues and family worked to complete it.

Stamper was born in South Bend and grew up on a farm in nearby Granger, Indiana, so the book is in part a salute to his hometown. The volume is extensively illustrated with images of significant local buildings — those lost and those still standing.

The book “was a labor of love for John,” says Jennifer Parker, head of the School of Architecture’s library and co-director of Notre Dame’s interdisciplinary Historic Urban Environments Lab (HUE).

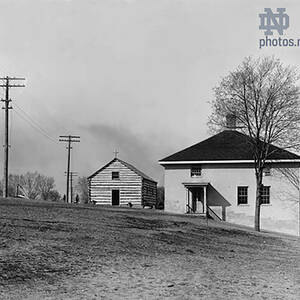

Notre Dame in its early years was more than two miles distant from the village of South Bend. City and campus for the most part grew separately.

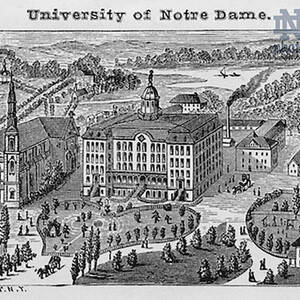

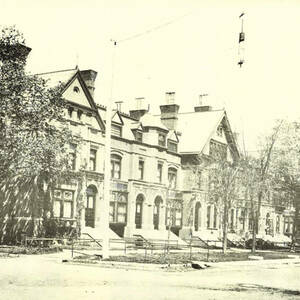

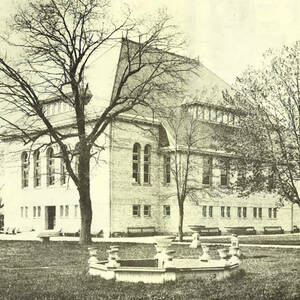

Rev. Edward Sorin, CSC, the University’s founder, recruited architects from Chicago and elsewhere to design some of its landmark buildings. After the Great Fire of 1879 destroyed the second Main Building and several other structures, Sorin quickly hired Chicago architect Willoughby Edbrooke to design a new Main Building, which later was topped with the Golden Dome. Edbrooke designed other important buildings on the Main Quad — Sorin Hall, Washington Hall and Science Hall (now LaFortune Student Center) — before going on to an illustrious national career.

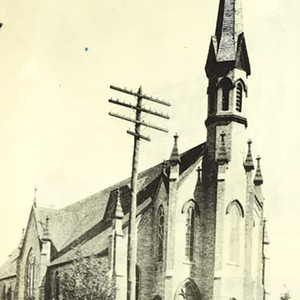

The Gothic revival style of what’s now the Basilica of the Sacred Heart influenced the design of a number of South Bend’s early churches, Stamper writes, including an 1882 church for St. Joseph’s Parish, which Sorin had founded near downtown in 1853. Structural concerns resulted in the demolition of that building in 1963. A modern church replaced it on the same site.

As South Bend grew into an industrial center in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, factory buildings rose throughout the city. Local industrialists — in particular, the Studebaker brothers of wagon and automaking fame, and the Olivers, who built the world’s largest plow factory in the city — helped spur South Bend’s commercial, civic and religious architecture.

The Studebakers turned often to Chicago architect Solon S. Beman — primarily remembered for designing Pullman, Illinois, the nation’s first planned industrial community. In South Bend, Beman designed the First Baptist Church in 1886 (demolished), the Studebaker Auditorium Building in 1898 (demolished), the Studebaker Administration Building in 1908 (vacant but still standing), the downtown YMCA in 1908 (demolished) and the white terra cotta-clad JMS Building in 1910, an office building that has been converted to apartments.

Meanwhile, the Oliver family in the 1880s and 1890s led construction of the Oliver Opera House, the elegant Oliver Row townhouses and the Oliver Hotel — all now gone. The J.D. Oliver family mansion, Copshaholm, a Romanesque Queen Anne showplace built in the 1890s, remains a South Bend icon and is part of The History Museum complex.

“Despite what some would say was exploitation of South Bend’s labor market and natural resources,” Stamper writes, “the Studebakers and the Olivers practiced a form of industrial paternalism that provided a livelihood for thousands and added greatly to the city’s civic realm as they built opera houses, a library, hotels, power plants, churches, streets, and whole housing districts.”

Some of the architects who worked at Notre Dame also practiced their craft at neighboring Saint Mary’s College.

A widely published 1875 aerial illustration of the college was actually a master plan and the campus developed in a considerably different manner, Stamper reports. The illustration shows a Gothic church at the end of the college’s avenue — a church that was never built.

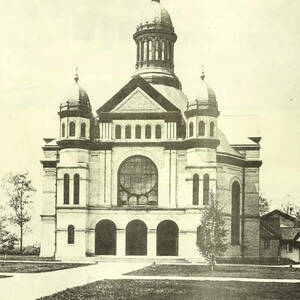

The Church of Our Lady of Loretto, featuring a circular or octagonal plan and designed in a Romanesque Revival style, was built southwest of the existing academic complex in 1885. While the campus church was dramatically altered from 1954 to ’56, a near-exact copy of it — the church of Notre Dame de Chicago by the same architect, Gregory Vigeant — still stands in Chicago.

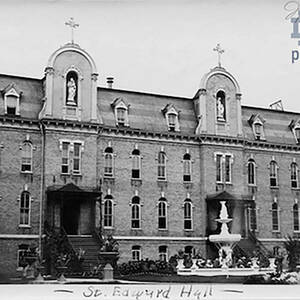

Willoughby Edbrooke also received commissions at Saint Mary’s. He designed the ornate Romanesque Revival Tower Building — topped with a steepled clock tower — in 1889 as the focal point of campus. It still stands, although the much larger Collegiate Hall (now Holy Cross Hall) was built just in front of it in 1902-03. Edbrooke also designed St. Angela Hall, constructed in 1892. The gymnasium-auditorium was torn down in 1975.

Nearly 40 commercial buildings in the Italianate or Second Empire style were built downtown during the 1870s and 1880s. Many of those buildings were replaced during a second commercial boom in the 1920s.

Stamper’s formal research for the book began in 1980. At that time, employed as director and planner of the local Historic Preservation Commission, he undertook a meticulous inventory of historic sites and structures in South Bend and St. Joseph County.

“The book is a reflection of John’s work far more than it’s a reflection of my work,” says Benjamin J. “Jack” Young ’23M.A., a doctoral student in history who revised Stamper’s manuscript for publication. Young’s work involved going through Stamper’s digital files and physical collections, editing the chapter drafts into a single manuscript and gathering additional photos and illustrations. He was committed to keeping the finished book in Stamper’s voice.

As a research associate at the HUE lab, Young has been a contributor to and an editor of Building South Bend, an interactive resource chronicling the city’s architectural history.

Stamper’s book also traces the decline of downtown South Bend. “After a profound economic disintegration in the 1960s, South Bend then suffered years of urban renewal that were meant to revive the city’s economy but ultimately did more harm than good,” he writes. Demolition of many downtown buildings made way for a short-lived pedestrian mall — leaving the city with fewer storefronts and many parking lots.

Some of the city’s premier structures were demolished during that era, including the 10-story Odd Fellows Building, the former Oliver Opera House and the Oliver Hotel. Such losses spurred historic preservation activism that continues today.

The downtown experienced something of an architectural renaissance in the 1970s with the creation of Century Center, the city’s convention center, on former industrial land along the St. Joseph River. Designed by the architectural team of Philip Johnson and John Burgee ’56, it was followed in 1982 by the glass-walled 1st Source Bank/Marriott Center (now a DoubleTree hotel), designed by the Chicago-based architect Helmut Jahn before he went on to international fame.

In contrast, Notre Dame’s brief foray into modernist architecture — for example, Hesburgh Library in 1963 and the Center for Continuing Education, built in 1965 and recently demolished — has yielded to an institutional preference for the collegiate Gothic style for most new campus buildings.

Published by Notre Dame Press, Stamper’s book arrives just as the city is crafting a new 20-year plan for downtown, a project that will involve the University. Notre Dame recently acquired the century-old former South Bend Tribune building, but hasn’t yet announced plans for it. University officials intend to work with city leaders and residents to repurpose the building and develop a comprehensive plan for the surrounding area.

The ideals of historic preservation and New Urbanism — a mixed-use design philosophy modeled on traditional walkable cities, with housing, jobs, entertainment and shopping in close proximity — should be brought to bear on the city’s renewal, according to Stamper, whose voluminous research files are now housed in the School of Architecture’s archives.

He recognized promise for the city’s future in recent development around Four Winds Field, the minor-league baseball stadium; in housing along the East Race Waterway; in the Eddy Street Commons mixed-use development near Notre Dame; in new downtown construction and the return of two-way streets in the commercial core.

“The challenge for South Bend today,” Stamper writes, “is to redefine its identity in response to the social, economic, and political changes of recent decades.”

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine. Contact her at mfosmoe@nd.edu or @mfosmoe