- 9th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- Schaal Prize: “Letting It All Be True," Mary Kate O'Leary '20

- Honorable Mention: “The Road Taken," Sara Felsenstein '12

- Honorable Mention: “The Storage Closet," Allie Griffith '17, '19M.Ed.

- Honorable Mention: “Chocolate Lessons," Andrew Robinson '17

- Honorable Mention: “A Day in the Life of a Millennial Homeowner,” Taylor Sheppard ’12

- Honorable Mention: “Invisible Motherhood,” Becky Wagner ’15

- Honorable Mention: “It’s Not Too Bad, Man,” Dylan Walter ’13

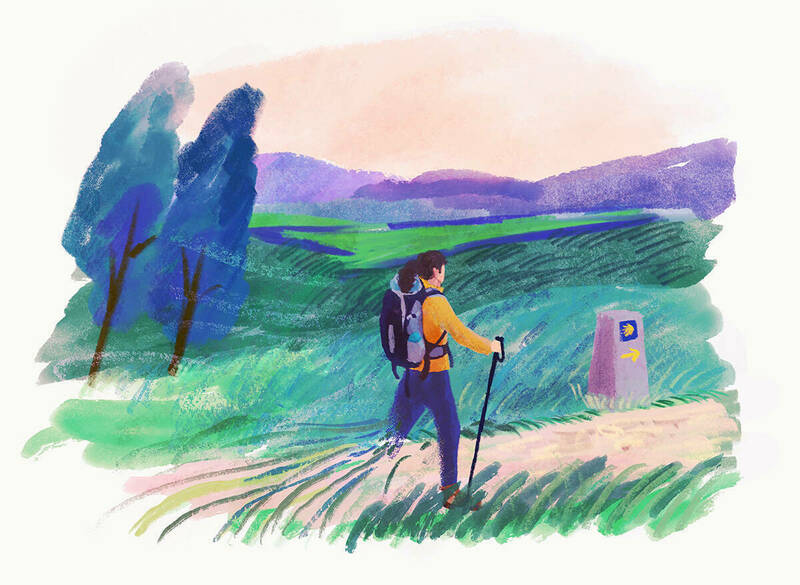

The Camino snuck up on me. I kept waiting for something to call it off: the rain, the government, a positive COVID-19 test. I was living in Santiago de Compostela, teaching English in a tiny pueblo in the northwest corner of Spain, hearing again and again how “normally” Santiago has such an energy thanks to the travelers celebrating their completion of the most ancient pilgrimage in the world, El Camino de Santiago. Because of “the situation,” as Galicians refer to it, I knew Santiago to be quiet and moody. I still can’t imagine the city as a massive finish line, full of pilgrims from every part of the globe.

But during that last week of March, my cynicism was for nothing. No cancellation, no COVID, barely any rain in the forecast. My friend Ellye and I got on a train to Sarria, 115 kilometers east of Santiago, with matching backpacks and borrowed trekking poles. My only expectations: We would take the train; we would walk back. Any revelation or spiritual insight gained along The Way would be a bonus.

After a year of Virtual This and Virtual That, there was something unbelievably fulfilling about a real, physical experience, one that came with muscle spasms and sunburns. Blindly following the stone markers that pointed to Santiago, I thought of all the people in all sorts of “situations” at other ends of other worlds who had walked the same steps. I wondered what questions drove them into the hills I was cursing. I wondered if they found any answers. Given my situation and the questions that forced me into my hiking boots, I wondered what exactly makes a pilgrimage, because it couldn’t be just the sandy roads and rolling hills.

I had thought my Camino started when I got off the train in Sarria. But kilometer by kilometer I realized it had begun the year before with an email from the president of Notre Dame saying that campus was closed “for the foreseeable future.” The world had changed in an instant, and my best friends and I were hunkered down in South Bend. We cried and complained and talked about nothing for days, then weeks, on end. The magnitude of how quickly life as we knew it ended still takes me by surprise. (I feel like the only thing that will soften the blow is some other earth-reorienting event. I do not find this thought comforting.)

On the darkest days of quarantine, my Notre Dame roommate and I made hazy plans for her to visit me in Europe once I made it there myself. I made my phone screen a picture of lavender fields in France: We were holding onto dreams like that as our last days of college passed unceremoniously. Then, almost before we noticed, we graduated. Little pomp, horrible circumstance, a livestream that my parents watched on an iPad. In eight months, I was supposedly moving to Spain, or so the Fulbright Commission had told me, but the moment felt nothing like it was “supposed to.”

The Camino firmly beneath my feet, I felt grounded for the first time in 12 months — physical pains taking my mind off abstract, theoretical ones. I was living in my body again. Over the previous year, I had been living in my mind or, more often than not, on my phone. At the height of the pandemic, in the absence of other distractions, I had passed days on end picking myself apart. I hadn’t used the time productively, and I scribbled in my journal about it: “If I ‘love’ writing, shouldn’t I be writing?” I spent my months at home sad and angry and confused, but telling myself I had no right to be since I “only” lost my last weeks of college.

In my journal, I gave endless qualifications: “I know I have it good. I know I shouldn’t be complaining.” I watched the endless, online competition of suffering, and logged off feeling worse for feeling bad. As I waited to move abroad, I happened into an opportunity I really loved, so then I felt bad about feeling good.

The pain and frustration and cynicism. The serendipity, the silver linings, the unforeseen plans that ended up being exactly right. It hadn’t been events that made my head spin, but my fruitless attempt to rationalize and justify how I felt about them.

When I moved, Spain looked nothing like the daydream I described in my application; instead it had a curfew, a mask mandate and a lockdown as soon as I arrived. Still, I thought, I shouldn’t complain, as if moving abroad amid a pandemic meant forfeiting the right to struggle.

Along the Camino, during Holy Week in the Galician countryside, I put my finger on what I had been feeling. Every decision to go out in public, to leave my house unnecessarily, had seemed like an ethical failure. Every complaint, every frustration, every grievance had felt bratty and tone-deaf and wrong. I had been zooming in and out of worldwide tragedy and everyday annoyances. No wonder I had whiplash.

On the Camino, things were different. It was a world waking up, resuming old rituals, even though it all felt new and foreign. After a year of abstract problems and ephemeral experiences, the Camino gave me straightforward, personal connection: no Zoom link required. A teacher tending bar at her husband’s restaurant smiled like she knew us. The storekeeper in a tiny, new age jewelry store gave us stones for free. When Ellye bought some earrings, the barista at an artisanal coffee shop asked, “Can I take a picture for my neighbor? She makes the jewelry, and it’s just been such a terrible year.” It was the distinct feeling of El Camino de Santiago coming back to life: an ancient, long- trodden path that is a study in consistency and change.

As the days stretched on, the path changed shape again and again — a forest turning into pueblo turning into highway and back into forest — I began to stitch together my definition of “pilgrimage.” To me, it is a lesson about moving forward even when it’s painful. Even when your blisters are excruciating and your calves are cramping and the hostel is still 3 kilometers up the road. It’s a lesson about letting the Grandiose Bucket List Item look different than expected.

I had always imagined the joy of the Camino to be meeting hundreds of pilgrims from around the world. In reality, the joy was spending five days outside without a mask. It wasn’t just the photo in front of Santiago’s cathedral, sign of a job well done. It was the detours and the hostel breakfasts and the moments when I truly thought I could not walk any farther, each part as much Camino as the last. The Way doesn’t fight its contradictions: It’s just as beautiful as it is ugly. It’s just as painful as it is rewarding. It lets it all be true.

I realized I could do the same: I could let each part of the pandemic be as valid as the others. The pain and frustration and cynicism. The serendipity, the silver linings, the unforeseen plans that ended up being exactly right. It hadn’t been events that made my head spin, but my fruitless attempt to rationalize and justify how I felt about them.

Somewhere around kilometer 87, we came upon this stunning field of wildflowers, no other pilgrims for miles. There was a fence and a farm and it was so sunny and so beautiful, the very beginning of spring. From that field on the other side of the world, I recalled the lockdown in freezing South Bend. That patch of Galician flowers gave me the perspective the French lavender on my phone had symbolized: We’re moving on, we’re getting better, we’re gonna be just fine. This field was messier and smelled vaguely of manure, but it was everything I needed. I breathed it in then turned my back: 28 kilometers to go. Santiago was in the distance.

Mary Kate O’Leary’s essay won first place in this magazine’s ninth annual Young Alumni Essay Contest — the Schaal Prize, named for former managing editor, Carol Schaal ‘91M.A. O’Leary, who majored in the Program of Liberal Studies and Spanish literature, teaches English in Spain through the Fulbright Program.