Editor’s Note: As a Notre Dame freshman in 1965, James Loverde boxed in the welterweight division of the 34th annual Bengal Bouts. This Magazine Classic, from our May 1979 issue, is a memoir of what, for Loverde, was an unforgettable week. His most recent magazine piece, reminiscing about a fleeting encounter with a recently deceased classmate, was published this week.

I won my first Bengal match on Monday, March 15, against Dad Tutko, an experienced sophomore. A slight euphoria remained with me late Tuesday afternoon when I strutted out of my Cavanaugh Hall room and walked to the nearby Field House to learn the name of my opponent for the semi-finals on Wednesday, Saint Patrick’s Day.

The Field House retained the odor of 66 years of sweat. When I closed my eyes, I felt as if I were standing in a clothes hamper with only a chill draft for ventilation. But as the wooden floor creaked and the door shut, I sensed even more the musty smell of disinfectant that lingered to haunt decades of athletes.

For boxers, at least, it was not the actual clash of combat that this smell brought to mind but the very anticipation of it. Whenever ring attendants carried buckets of mouthpieces floating in disinfectant, the scent would trigger streams of consternation in me that I would try to interpret—like a Celtic druid studying the flow of a slain chieftain’s blood, or an ancient Roman augur judging the gods’ favor by the direction of lightning.

But as I saw my opponent’s name on the list under a glass case, my fears became concrete. Wednesday’s opponent would be Pat Farrell, the defending Bengals’ champion and a national Golden Gloves semifinalist. On Monday, he had TKO’d his opponent early in the first round. I stared at our bracketed names and thought of my grandmother chopping mushrooms in her kitchen and answering all soothsayers with a Tuscan pragmatism: “La vita e TOUGH-a!”

The calm of near certainty fell over me: I would almost surely lose. But I consoled myself: I was in good condition and was considered a good beginning boxer. I had only to do my best.

I also noticed that few Italian names were on that list, which the Irish dominated. Despite another beloved grandmother and a cohort of friends who were Irish, that disproportion was significant: I had not signed up for the Bengals to be knocked out by a Farrell.

“What the hell, stick your head in and see what you can do,” a friend told me back at the hall. After dinner, I stopped in a room full of dorm mates on my way to the library. After some forced joking, they grew silent and regarded me with curious stares. Then I went to study for a German midterm exam. The exam, too, was scheduled for the following evening.

On Wednesday, my two roommates and others went into South Bend after morning classes to celebrate Saint Patrick's Day at any establishment that would admit them. I spent most of the day resting and trying to study German. In the afternoon, my classmates returned from their partying with a staggering panache and an insistence on looking drunk and carefree. Some freshmen outside my window grabbed what little snow that was left and started a skirmish with upperclassmen from Zahm Hall.

I lay on my bed and envied them, and wondered what conceit led me to set myself apart from them on that day. Then I realized that most of them had performed on gridirons, diamonds and mats while I had sat in the stands. That night, it would be my turn.

During the long preseasons at Notre Dame, the sun often appeared late in the afternoon.

It would splash a dull yellow onto the corners of the buildings and fall in patches on the ground. In suggesting warmth, the sunlight served only to make the weather seem colder. But the sun hid on that afternoon, as if to deny me any good omen.

I walked to the South Dining Hall around four for a prefight dinner of steak, toast with honey, and fruit juice. Lighter-hearted boxers were always among us, but the usual badgering was subdued. Those with a penchant for bragging had either fallen out or quieted down a month before, when the sparring started. After I finished, I walked up to Pat Farrell by the coat rack. I noticed again his deep-set eyes and the streamlined features of his expressionless face. I told him I would probably be a little late because of an exam.

“Okay. We don’t want to start without you,” he said, as he put his “Champ” jacket on over a kelly green pullover. Then I saw Nappy, a short, gray-haired man. I told him the same thing. “All right, don’t worry,” he snapped with a quick nod.

The German exam started at 7:30. My professor, Albert Wimmer, greeted me with a wide smile. “Come on, you have to fight the champion tonight,” he said. Then he led me quickly through the six testing stations. When I completed the exam. I thanked him and walked to the Field House.

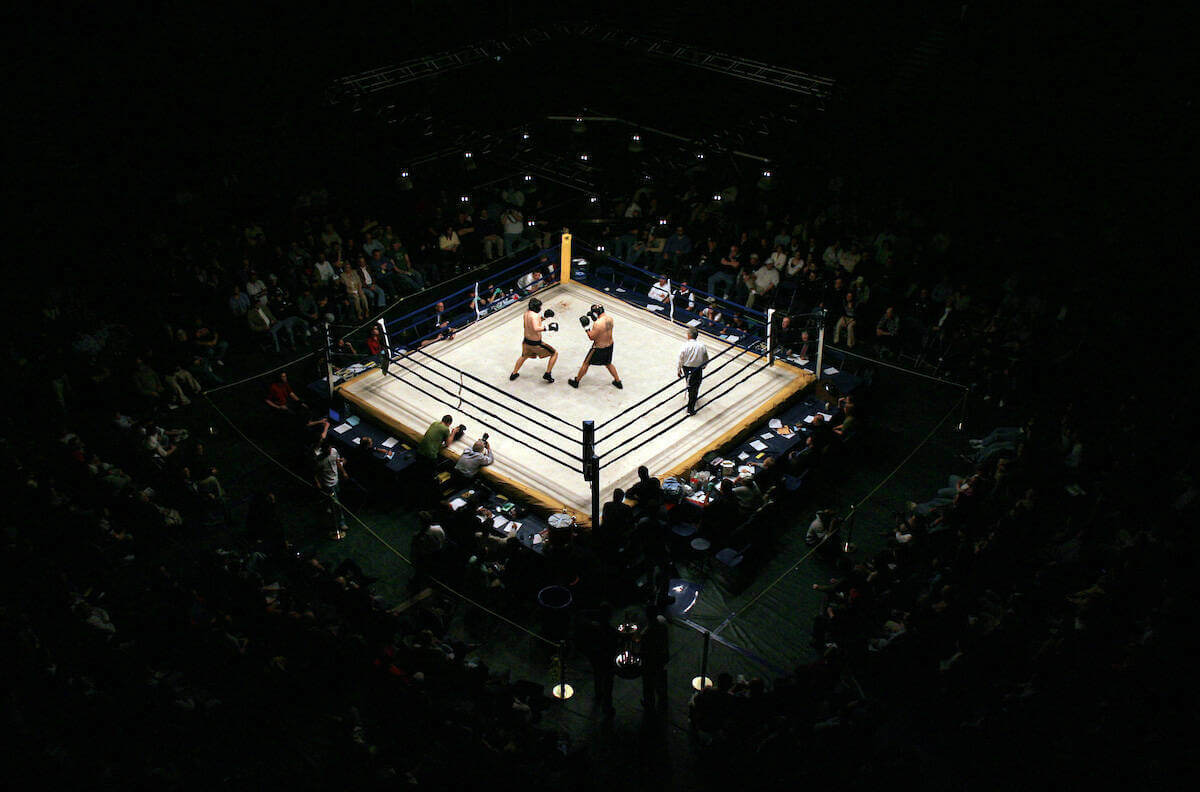

One end of the Field House was dark and quiet. But at the other end, lights glared over a ring and a crowd hollered from surrounding bleachers. I crossed the cinder track and the dirt floor and walked downstairs to the dressing room.

I exchanged silent greetings with other boxers and changed quickly into a pair of gold trunks with blue stripes. The trunks’ shine added to my discomfort. I longed for the trusty sweat clothes I had worked out in for weeks. And I could never get used to the hard protective cup between my legs.

In the training room, a Knights of Columbus volunteer taped my hands and wrists in a complicated manner. I liked to think that this rite was an old, esoteric mystery unknown outside the K. of C., which sponsored the Bengals every year. Meanwhile, heaps of tape cut from returning boxers lay in a pile by the doorway, alongside towels smudged with dirt and blood. A defeated combatant lay holding his nose on another padded table.

The good knight fastened a headguard on me and tied a pair of new sixteen-ounce gloves over my wrapped hands. Then he ran wide tape over the laces. The gloves felt awkward, and I wondered how I could use what speed I had with such cumbersome appendages.

Pat Farrell was also getting his gloves tied on and we wished each other luck. While the announcer, a tall upperclassman in a tuxedo, asked me how I pronounced my last name, I noticed that Farrell had arms and legs like Popeye, with bigger chunks of muscles in his calves and forearms than in his upper arms and thighs. His face was now shining with a coat of petroleum jelly, a precaution I had neglected.

We sat on a wooden bench with robes draped over our shoulders waiting for our turn. Even then, I felt less anticipation than I had felt before my first match. But I thought of how my classmates had avoided me like a condemned man, and I was determined to fight aggressively. But until then, there was time for conversation:

“So, where are you from, Pat?” I asked.

“Prairie du Chien. It’s up in the southwestern part of Wisconsin. How about you?”

“Melrose Park, just west of Chicago. Say, lemme ask you something. It’s all right to keep swinging in a clinch, isn’t it?”

“Sure. As long as the punches are legal — you know, not below the belt or any rabbit punches.”

“Thanks.”

The previous fight’s decision was announced to loud applause. Farrell and I stood and walked out. We stopped at the foot of the bleachers, where Nappy stood in a gray suit.

“Okay, the winner of this match wins a jacket and advances to the finals,” he said in his high voice. “So give it all you’ve got.”

The two preceding boxers walked past us like strangers in a dream as I crossed my arms and followed Farrell into the ring. Cheers began to mount like a junk shop orchestra tuning up.

Mine was the “gold” corner, nearer the dressing room. My second, a senior named Mike Smith, frowned at me with knotted eyebrows. “Ready?”

I nodded. Smith was a fine boxer. So was Jude Lenahan, Farrell’s second and Smith’s light-heavyweight opponent on Friday. Smith had a boyish, clean-cut face and was trying to look stern. But he rarely smiled anyway, so it was hard to tell the difference.

The announcer introduced Farrell first. The cheers for him were unlike those for the rest of us. They were more like the kind heard at professional fights: firm, sustained hollers like swords banging on shields, and cruder howls for blood. When I was introduced, the cheers of my freshman friends matched my predicament: determined, isolated and forlorn.

Smith took off my robe and I sat on a stool with my arms hanging on the middle ropes and my head resting against the turn buckle behind me. While trying to breathe slowly and relax, I felt a surge of anger: anger because I knew that most of the crowd thought I wouldn’t last long, anger for slights suffered in high school while failing at basketball and football, anger because I had to be angry. I knew that laying back would be disastrous.

The referee, a stout old man, signaled Farrell and me to center ring. He gave us instructions, and Farrell and I again wished each other luck.

“Seconds out,” one of the men at the timekeeper’s table said. I faced the ringpost, made a sign of the cross and turned around.

The bell rang and I stepped forward toward center ring. Farrell closed in. Though he was only an inch or two taller, he seemed to loom over me like a predatory bird. I felt a flutter around my ears and charged straight ahead.

While hurling straight rights and lefts at Farrell, I also managed to block the hooks he was throwing at me. I backed him up against the ropes. A roar went up. After some maneuvering, he rushed at me again while throwing more hooks. Again, I landed straight punches and forced him to retreat. When the bell sounded to end the first round, I felt confident.

“Okay, Jim” said the ever-dour Smith. “This is your night. You’re going to score the big upset. Just stay on the attack.”

Round two began. I again paced forward to take a stand at center ring. Farrell greeted me with a quick feint to the midsection. When I obligingly lowered my guard, he shot a left jab to my head that almost knocked me out. I managed to recover quickly and stay in close, while enduring a flurry of blows.

“Straight punches, Pat! Straight punches!” Jude Lenahan was shouting. Farrell’s punches were straight indeed.

Round three. I kept cramping Farrell. He got to repeat his devastating jab just one more time — at the beginning of the round just after we touched gloves. Again, I recoiled at once from a bent-back position and resumed my strategy. There was never a need to worry about what to do in a clinch. There wasn’t any.

I could hear individual voices hollering encouragement, but the third round was more difficult than the second. At one point, Farrell’s pummeling got so consistent that I actually paused for an instant to look at an attractive blonde lady seated at ringside. I distinctly remember her staring back quite casually, not surprised at all.

But in the face of a less comely Farrell and his leather fists, I felt my mouthpiece fall out of place and turn sideways. Now was a moment for high drama and one last rally. I spit out the mouthpiece as far as I could and raised my fists with a flourish straight out of the movie The Quiet Man. Another roar went up.

The crowd’s approval did not make the task of staying on my feet any easier. I abandoned my fundamental stance and swang wildly, while Farrell’s punches landed harder than ever. The final seconds of the third round seemed to last longer than all the preceding minutes of the fight. When the bell finally rang, I again had Farrell against the ropes, while his salvo was continuing unchecked. The sound of the bell settled on me like a splash of warm water.

Farrell and I stopped immediately. “Good fight, Jim,” he said, scarcely out of breath. He shook my right hand with both gloves like a banker who had just negotiated a loan. The crowd was still cheering as Farrell and I walked back and sat down. Mike Smith’s congratulations seemed anticlimactic after his exhortations between rounds. So did the announcement that Pat Farrell had won by a unanimous decision.

Nappy stopped us on our way to the dressing room. “You’re going to be a great one,” he told me.

After a manager removed my gloves, headgear and tape, I lay down on a padded training table. Then all the ducts of adolescent delight opened wide and sent a gush of tears down my face. I got up to look at myself in a full-length wall mirror and I burst out laughing.

Though I never bled much in boxing matches, my left eye was closed and its ridge was swollen like a plum. Another puff swelled under my right eye and my upper lip stuck out like a muzzle. A door opened, and fellow boxers came in for the customary exchange of compliments.

The next Friday I got my German exam back — a “B.” After that evening’s boxing finals, Nappy gave awards to boxers who had not won championships. When he announced the winner of the Rupert Mills Memorial Trophy for “best first-year boxer,” I shook Nappy’s hand at center ring, clutched the trophy and relished the close of a glorious week.

Two years later, in his junior year, Loverde captured the Bengals championship. Today, he lives in Chicago. His articles have appeared in Sports Illustrated, Chicago magazine and the Chicago Reader, and his poetry in Rolling Stone.