One evening last semester I made arrangements to deliver a manuscript to one of our young campus leaders named Tom before or after the 11 p.m. Mass in Farley. Tom came into the chapel after the Mass had started, sometime around the Gospel; at Communion time, he received the Eucharist with the rest of the group. Immediately after the liturgy was completed , he came into the sacristy to see me.

“The Mass was very moving,” he said. “I’m always deeply stirred by the Mass. Its age and tradition make it a very special form of worship.”

I was pleased by his enthusiasm because I knew his devotional life had been in a state of drift. I said, “I am glad you came over to join us.”

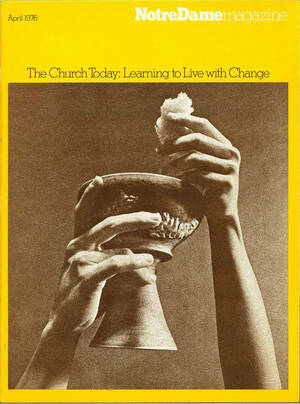

- In April 1976, the magazine assessed the state of Catholicism, a perennial topic of scrutiny over the years, with the cover treatment, “Learning to Live with Change.” We still are.

- On Ancient Rituals and Modern Yougth, Robert F. Griffin, C.S.C., ’49

- Chapin St. and the Meaning of Social Justice, Bro. Bruce Lescher, C.S.C., ’68

- Liturgical Reform: What Next?

“So am I,” he said. “It’s the first time in over a year that I’ve gone to Mass. It’s been a lot longer than that—years maybe—since I went to Mass as a matter of choice . . . without doing it to please my family, or as an accommodation to help out a friend.”

Since he seemed willing to talk about it, I asked: “Could you tell me the reason why you don’t go to Mass?”

“Well,” he said, “I guess I really don’t believe any of it.”

“Are you telling me you’re an agnostic?”

“I prefer,” he said, “to call myself an atheist. It seems more honest.”

“Tom,” I said, “if you are an atheist, why did you just now go to Communion?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I just felt moved to share in the ancient ritual of the Christian faith.”

Months later, we talked of the matter again; I was still taken aback as to why a professed atheist would want to receive the Eucharist. I recalled for him the conversation in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist, after Stephen Dedalus has refused his mother’s wish that he make his Easter duty.

Do you fear, then, Cranly asked, that the God of the Roman Catholics would strike you dead and damn you if you made a sacrilegious communion?

The God of the Roman Catholics could do that now, Stephen said. I fear more than that the chemical action which would be set up in my soul by a false homage to a symbol behind which are massed 20 centuries of authority and veneration.

“I fear that too,” Tom said. “I don’t live without fear.”

“Then why did you go to Communion, Tom?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “It’s just one of the mysteries of doubt.”

It is my opinion that Irishmen have more difficulties of faith, either of losing belief or of finding it, than any other group I know. “There is more faith in an honest doubt than in all the creeds of man,” Tennyson once opined. Maybe so, but I always feel like a dishonest fool when I try to turn a chap’s opinion inside out, insisting on the paradox or irony that sees the libertine’s lechering as his wistful quest to become pure, or that judges the blasphemer who burns down the temple to be acting from motives of the heart’s having reasons that the reason knows not of.

I am too old, you see, to need to kid myself, or to want to kid myself, about matters like faith, or religious experience, or theology, or the role of God in human affairs. I’ve been a priest for nearly 22 years; I’ve been a Catholic for over 30 years; before that I trudged in and out of Protestant churches as though they were supermarkets. Baptismally speaking, I have been sprinkled, poured on, and totally immersed. Twice, under the hands of bishops, Catholic and Anglican, I have sacramentally submitted myself to the Descent of the Dove. From the earliest remembered moments of my life, there has never been a time I wasn’t, in some way, conscious of God. From the age of four or five, when I sang the anthems of salvation at my grandmother’s knee, I have been stirred in my emotions by the stories of the Lord Who commanded the wind and the sea, and Who rose from the dead on Easter morning. There was a time when I ran after faith experiences; now, I don’t have to run anymore. Christ is happening all around me. In the ordinary events of life, I find the Lord busily revealing himself in the simple gifts, as in liturgies where he is recognized in the breaking of the bread.

Every year or two, some group, or some campus publication asks questions about the state of the Catholic religion at Notre Dame these days. I am too old to pretend that I understand how God and our campus people are dealing with each other. To me, Notre Dame seems to be one of the most religiously exciting places to be found anywhere, more exciting even than the Vatican (if I may be whimsical), where the Holy Spirit is at work night and day, keeping the pope infallible in matters of faith and morals.

Mass attendance is high—higher, I think, than it has ever been in recent years. The candles at the Grotto are continuously blazing rack upon rack. Theology is one of our most respected disciplines, and some of our brightest students are running around with Bibles under their arms, talking of Reuther and Rahner. Practically every sensitive Christian in town is involved in some project intended to save the community, the country or the globe. From many visible signs, Notre Dame, Our Mother, is still flourishing as a Catholic institution.

Only sometimes I remember that once, during the Ages of Faith, there was a beloved priest and counselor and confessor on this campus. For 17 years he was the prefect of religion: later, he became President of Notre Dame, and at the time of his death he was the cardinal archbishop of Philadelphia. His name was John Francis O’Hara.

Sometimes on Saturday afternoons after the 5:15 Mass at Sacred Heart Church or on Sunday afternoons when I have had baptisms, I pause for a moment to pray at the tomb of Cardinal O’Hara. I feel that I have a special need of Father O’Hara’s prayers because, through a kind of apostolic succession, some of his pastoral cares as prefect of religion now belong to me. In the evolution of office, the prefect of religion became the university chaplain, then the university chaplain became the director of campus ministry. Now, by title, I am the university chaplain and Father Bill Toohey is the campus ministry director.

There are man of us walking in Father O’Hara’s footsteps and living in his shadow. And his zeal and effectiveness are the standard against which his successors must measure themselves, as later football coaches must surely measure themselves and be measured by the greatness of the incomparable Rockne.

None of us can keep Notre Dame Catholic as it was Catholic in the days of Father O’Hara. For example, he disapproved of the works of Ernest Hemingway, and would not allow them to be placed on the library shelves. (There were other proscribed books and authors also.) If a chaplain tried that today, he would be giggled at as silly.

Father O’Hara may have felt competent to take after the loose-minded professors; few of us today feel qualified to take after the loose-minded professors, whatever their discipline of study. But neither can a chaplain announce, as O’Hara announced in 1921, that each student was averaging 3.5 Communions per week ; or two rejoice in the statistics o fa later year that the number of daily Communions was average a high of 1,910 out of a student body of 3,000.

For O’Hara, the boy who was receiving Communion daily was constantly living in a state of grace; therefore his other problems would take care of themselves. To encourage daily Communion, he would distribute the sacrament until noonday to the late risers who had missed attending Mass. He dismissed the criticism that he was making Communion too easily available: “While part of the grace of Holy Communion depends upon the sacrifice made by the individual, the great grace of the sacrament comes from Our Lord Himself working in the soul.”

In other words, he was relying on a sacramental efficacy that theologians call the ex opere operato effect: that is to say, the spiritual benefits of a sacrament come from the sacrament itself, and are not dependent on the fervor and zeal of the recipient, granting he is already in a state of grace. Contemporary chaplains do not have the peace of mind that arises from so simple a view of the sacrament because modern theologians tell contemporary chaplains that the ex opere operato formula makes them nervous, suggesting, as it seems, that the sacrament is automatic and magical. Sacraments, the modern theologian says, are not something we receive, but something we do, celebrating our own existence as Christians.

Considering the more sophisticated theology in use today, I say again that none of us can keep Notre Dame Catholic as it was Catholic in the days of Father O’Hara.

There are verbal portraits that have survived of O’Hara among the students: quick-motioned, energetic, smoking too heavily, taking time out of his 18-hour day to match wits, besting the students in their own kind of game. But what would have converted us to O’Hara, as it converted our fathers, was his unflagging love and devotion to students; uniting that love to the nimbleness of his wit and the depth of his faith, he brought all his sons home to their Father’s house. He would rouse them out of bed to attend Mass; he would note the students who were absent from chapel, and he would send them notes reminding them of Easter duties to be made, of confessions that seemed overdue, of Communions that had been neglected. He knew every face, every name, every hometown, every personal history; and quite simply, nobody has ever matched his success. That is why, as one of his successors, I am haunted by the memory of the chaste, gleaming marble of his tomb, with its Mestrovic statue of the Prodigal Son and the red roses that the alumni send twice a week, as though for their own peerless parson they were matching the romantic legends of the roses left by lovers on Valentino’s grave. I remember with emotion O’Hara’s homecoming, when he returned in death to Notre Dame, where his sleep in the Lord seems like a ministry of caring from the best of all the Notre Dame chaplains.

I think to myself: if the judgment of other chaplains were to be given into his hands, as the judgment of Irishmen has been promised to St. Patrick in that day when all flesh shall see their God, what can we say of the Notre Dame of these years as evidence we have stood by the Faith?

Were there 1,000, 2,000, 5,000 students who went to Communion today, last Sunday? I believe that number is very high; I know also there are hundreds who never go to Mass at all. Is Hemingway placed on the library shelves? It would be absurd not to place him there; but O’Hara knew that. O’Hara lived to see Hemingway win the Nobel Prize; the Cardinal and the laureate died within a year of each other. Are confessions being heard in the hall chapels? I would guess that Father O’Hara heard more confessions in a week than most of us now hear in a year. This is not from neglect of chaplains; it is due to the changes since Vatican II. As Father Thomas McAvoy, who was University archivist for many years, remarked: “O’Hara did not belong to the aggiornamento.”

These are the easy questions. But how does one render an accounting of the Christianity of a place where the numbers game with the sacraments does not necessarily mean anything, because faith and a reception of the sacraments do not always go hand in hand? There is a whole group of Notre Dame students who attend the celebrations of the Eucharist, not out of a belief in the mercy of Christ (though they are perfectly assured of the mercy of Christ); but out of a belief in their own goodness and the goodness of their friends assembled together (as they might say) in a community of love and sharing.

It is a trite trick to talk of a place as though one were giving an account to some figure in the pas. But for me, as for everyone, O’Hara is the symbol of a great tradition of Catholicism at Notre Dame. If I could explain to him how we too have a great tradition of Catholicism, differing from the past, yet related to the past and growing out of it, I could be more at peace with myself as a campus minister not needing to live with a sense of the past betrayed. A 2,000-year tradition of Christianity should not have changed very much from one decade to another. Yet, it has changed. Notre Dame has changed. I would have to say that the campus, like the country and the world itself, has suffered a loss of innocence. For me, it is the innocence that is so characteristic of all those religious bulletins, all those students averaging 3.5 Communions a week, all those confessions whispered into the prefect’s ear, morning and evening, for 17 years. The other quality of our contemporary Catholicism is how much more involved we are with the Mystic Body of suffering in the world. There has been an abandonment of the theology urging students to “hit the box” and “hit the rail” before you hit the road, because death waits at the crossroads, and you may be in a state of mortal sin. Mortal sin seems a more remote enemy than the famines in Africa and Bangladesh, or the loneliness and neglect that make old age so terrifying to so many, or the varied illnesses of children, or the abortion laws that help doctors and parents destroy more than a million half-formed infants a year.

This is a generation of students who have grown into adulthood since Vatican II, and it is a generation with global concerns. Not only has there been a relaxation of the moral and canonical legalisms within the Church, there have been all those other events of history that have revealed the world to itself as a wounded, bleeding place. Priests, nuns, and lay journalists have been busy for 10 years pointing out how a politically minded Church has been dragging its feet in helping out at the crises centers. The ancient institution is suffering a loss of credibility in being accepted as a Community of Those Who Care.

Would it be a weak answer, then, to say to his venerable eminence: Notre Dame is a fine and Catholic place, and its happiest manifestation of religion is the intensity with which the young people care? The young people care; the priests care; the faculty care; the administrators care; the secretaries care; the hall staffs care; the maids and janitors, the maintenance men and the security guards all care; and the Greatest Carer of Them All is Father Hesburgh, who comes home to campus to give us lessons. We care not only for Biafrans, Cambodians, Chileans, Guatemalans, and Vietnamese; sometimes, incredibly and beautifully, we care for one another. Notre Dame people have always cared about one another, even when they hurt each other with vicious or careless behavior. That caring, sinewed sacramentally in the life of the Church, is what binds our generation to O’Hara’s generation. It is the quality of caring that was in O’Hara that makes him a folk hero to us chaplains today.

It is the union between the caring and the service, to the faith and the liturgy, that gives such vibrance to the Catholicism that works and plays on this campus these years; that union is felt in every Mass that is said here, which is as it should be in an age when theology stresses the social character of the sacramental graces. You should see how beautifully this union is happening with the freshmen, who are experiencing it as a heritage of the special place called Notre Dame.

Of course, I can’t prove any of these things to you, but I can’t prove the presence of the Lord in the Eucharist, either. To tell the truth, I don’t even want to try. That is why I have avoided cataloguing the prayer groups and the service organizations which are the visible signs of an invisible grace.