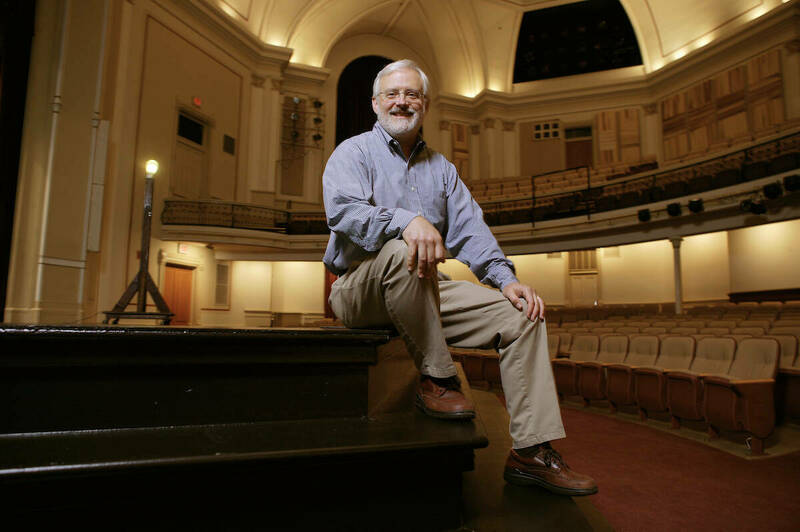

Pilkinton in 2004, back when he still haunted Washington Hall. Photo by Matt Cashore

Pilkinton in 2004, back when he still haunted Washington Hall. Photo by Matt Cashore

Editor’s Note: This is the third in a Notre Dame Magazine series chronicling the interior renovation of Washington Hall, the University’s 143-year-old campus auditorium.

- The Once and Future Washington Hall

- A Retrospective Renovation

- Setting the Scene

- Questionnaire: Mark Pilkinton

- Dream Job

Mark Pilkinton had been teaching theater history, theory and criticism at Notre Dame for 20 years before the University built the DeBartolo Performing Arts Center in 2004, seeking to anchor what has become the “arts district” along campus’ southern edge. The shifting locus of the University’s main stage attractions left Washington Hall, erected in 1882, in a sort of light-duty limbo — an unfamiliar supporting role for a building that Pilkinton notes was accustomed to playing the lead.

The professor emeritus, who retired from teaching in 2016, knows Washington Hall as well as anyone; he directed a dozen plays on its stage, and his own favorite moments inside one of Notre Dame’s most storied buildings came on opening nights when “the audience entered, the house lights dimmed and the magic began.”

Pilkinton is also author of Washington Hall at Notre Dame: Crossroads of the University, 1864-2004, a 300-page history of the beloved landmark that he concluded by calling for the rehabilitation of its original interior decoration, completed in 1894 but painted over in 1956. As Pilkinton explains in this interview, that dream was realized this summer by the University’s go-to art restorationists at Conrad Schmitt Studios.

What prompted you to become the authority on this unique building?

Well, the original idea for the book was actually from Tom Barkes ’98MBA, my first hire as chair of the [communication and theatre] department in 1984. [Back then] Tom was the manager of Washington Hall, and he thought somebody should write a history of the building. We realized there were references to a Washington Hall before 1882, so this is not the only Washington Hall. Well, years later, I was the one who took on that chore, and I mean it was a labor of love, and I spent four years on it.

When the fire of 1879 occurred, it burned down the music hall, which was separate from the exhibition hall, Washington Hall, [which] was turned into a dormitory for workers to rebuild the Main Building. And then they started building this building that we know as Washington Hall. For a short time, they were going to use the old Washington Hall for other purposes, but they didn’t; they demolished it. And they combined essentially the music hall and the exhibition hall into one building.

After the building was up, they realized, well, we need to decorate the inside in the style of the time. And the University had been in touch with [the artist] Signor [Luigi] Gregori; he had done the Main Building and all that. They commissioned him to do these portraits. They had a vision, an idea, and then they had a very talented person in Chicago [artist Louis Rusca] actually execute the work. He did all the interior painting and all the beautiful trompe l’oeil effect that they’re finding now.

Why do you think of Washington Hall as the crossroads of Notre Dame?

Everything happened there, from the first moment you arrived as a student. You went there for your orientation meeting. If you were going to get married [in a later era], you went there for your Cana classes. You would go there to do plays, for musical events, for anything that was going on, assemblies. Even graduation, early on. And everybody could get inside it. All the students, believe it or not. And all the faculty could get into that building and could fill it up and they could all be there. It was the secular focus of the University. And it fulfilled that role for a very long time. Of course, the University outgrew it, and now we’d have to go into the stadium if we wanted to have all the students, all the faculty, everybody attend a single event.

What would you put in a highlight reel of Washington Hall’s lifespan?

Well, I think the actual building of it — that replacement after the fire, the vision to combine the music hall and the exhibition hall into basically a performing arts center. The [architect Willoughby] Edbrooke building we have now, that was really an 1882 performing arts center.

And then of course, I think the fact that so much University life was in that building over time. I have students who have said, “I lived in Washington Hall when I was a student and doing plays. We just lived there. We were in the middle of the University, we were close to our dorm, and we were there rehearsing 20 hours a week.”

I mean, that’s like a half-time job at least. And it was that first center of coeducation, because remember, Father Art Harvey, CSC, ’47 [the longtime chair of the theater department], especially brought women over from Saint Mary’s in large numbers, and they had this system where [they] could actively pursue theater. And so, long before 1972, you had this tremendous interaction between men and women in Washington Hall that didn’t really occur anywhere else on campus. It was a very progressive, very innovative sort of space. Now, it’s hard for us to imagine because it’s kind of an antique, isn’t it? A little jewel box.

Imagine I’m a smart, well-read student in, say the spring of 1896, and while waiting for a play to begin, I look around and above me. What do I see and what might it mean to me?

Well, first of all, over the proscenium, you would see the portrait of George Washington with “for God and country” written in Latin. And I think he was holding a copy of the Declaration of Independence. And here you are a Catholic boy at a Catholic university in the Midwest, and you are affirming that you’re an American in this building named after the father of the country.

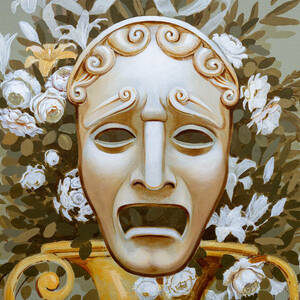

And then you’d look over to your right and see Shakespeare, look over to your left and see a portrait of Molière. You see the muses of tragedy and comedy above them. And you would see on the proscenium arches Demosthenes and Cicero, a great Greek orator and a great Roman orator. And then if you looked carefully among the leaves and everything going up the sides, you would see the names of composers and music notes. And you’d see the names of [Maximilian] Girac and [Father Edward] Lilly, CSC, the fathers of the music program at Notre Dame.

All that connection of Notre Dame to music and poetry, comedy, tragedy, and then of course to patriotism: All that tied into the center of secular life at Notre Dame.

Why was that close identification of being Catholic and American so important the time?

I mean, this goes all the way from the Know Nothings, right? At the time the University was created, all the way through to the 1920s, to the Ku Klux Klan, Catholics were challenged. It’s hard for Catholics today to think about, even as late as John Kennedy running for president, the anti-Catholicism in the country. Even in 1960 it was still profound.

And you got this French order — think about it — that comes out of nowhere and sets up this university. You could imagine the kind of issues they had with the town and all that kind of thing. It’s very much like what we have right now in this country. These people who don’t want any immigration and want to send everybody back. And I mean, that’s what was happening. Send all the Italians back; send all the Irish back.

And so, I think that there was a real reason to say you can be a good Catholic and you can be a good American. There is no daylight between those two. I think Father Sorin was brilliant in establishing that early on and never saying, “Oh no, we’re a little, elite European-focused place where people speak French.” No, we’re American. This is what America is, and we are it. And I think they were hugely successful with that.

Did the symbolic power of the art change much as Notre Dame witnessed the 20th century?

Well, it’s interesting. Clearly, when it was painted over in 1956, we were into a phase where we didn’t have respect for the past. I recall people lowering high ceilings in old houses, closing off fireplaces, “modernizing.” I remember urban renewal, where they go in to build a highway in the middle of a city and tear down block after block after block of 1880s townhouses that were just gorgeous. We lost our respect for our past and ended up kind of bulldozing everything. Whitewashing those walls [at Washington Hall] was really what was happening everywhere.

It was like visual noise to a theater person. You want a very neutral space. You want a soft, matte black, you want battleship gray, so your show is the focus, and people are not trying to read names on the proscenium arch and things like that. It was more the idea of, “Let’s turn it into a real theater.” Although now when you go in to redo these historic theaters and cinema houses, as you know, they’re restoring the gold leaf and all. We are now post-postmodern, whatever period we’re in. But we are clearly in a phase now where we’ve gained respect once again for that.

How did you react to the news of the restoration?

The fact that that stuff is underneath that paint to me is just remarkable. They can take off those layers and get down to it. So I was thrilled.

And then of course, immediately concerned: Well, wait a minute, how are you going to avoid the controversies you had in the Main Building? You’ve got to be careful with this because when you excavate the past, you bring up things that everyone’s not thrilled about.

Were there particular sensitivities that concerned you?

Well, yes. I was not involved in any of the decision making, bear in mind. I was not in the room where it happened. But yeah, I immediately thought, OK, you’ve got four [of the nine] muses. They’re all daughters of Zeus, so they’re white women. Our University today is a very multicultural, diversified, inclusive place. And we don’t want anyone to go into a space and feel like they’re not being respected or that their culture doesn’t matter. So [aside] from the four muses, all the other portraits were dead white men. And then, of course, you’ve got Washington. Bless his heart, he was the father of the country, but he was a slaveholder until his death.

So, what do you do? How do you handle that? How do you deal with the kind of representation we expect to be there today? I’m not even sure what the solutions are. I know they’re doing emblematic things now. That does take away from the daughters of Zeus, but it’s been a long time since anybody has known anything about the daughters of Zeus.

When you were writing the book, you called for a restoration. Did you suspect all along that the artwork might be salvageable beneath the white and gray paint?

Yes. I thought there was a good chance that the artwork under the paint would be there. I didn’t think that the portraits would be, because they were canvas and they were plastered on, but I suspected there might be a degree of survival of the stuff underneath. It’s just pretty incredible how much is there. And it’s beautiful. Don’t you think it’s amazing what they did back then?

We had hints. There was a closet somewhere that they had never touched. There was a ceiling above the light booths. In the back of the theater, there was a faux ceiling, and then there’s a real ceiling above it, the arch ceiling, and it still had decoration on it, so we knew the decoration was there. We just didn’t know how much of it was salvageable or could be redone.

When do you plan to come see the results of the restoration?

I look forward to coming back to see it. I think it’s going to turn it back into that jewel box.

The building, when I arrived in ’84, it was like, “Gosh, should we just condemn this building and tear it down and start over?” They had done a renovation, but they hadn’t air conditioned it. I mean, they were just doing it on the cheap at that point. They added air conditioning later. And even when they did that, they thought about doing it temporarily just so Father Hesburgh could give a famous farewell speech from there. But it had some years of neglect, and it’s really great to see that it’s going to be a wonderful [space].

Maybe they’ll surprise you by changing the name from Washington Hall to Pilkinton Hall.

Yeah, I think that’s not likely to happen. But of course, Washington was an Episcopalian, and I am, too. So I guess an Episcopalian can have a building named for him at Notre Dame. But I think we’ll stick with the good American/good Catholic thing and that reverence of Washington. That was a very smart move on Father Sorin’s part.

How do you think about the future of Washington Hall?

There’s a writer I really admire, [Louis] Althusser — the idea that cultures reflect their ideology physically. It’s not what cultures say, it’s what they actually do, and it’s physically represented. And so, if you think of Washington Hall, there were no portraits of old popes and saints. Think what a Catholic university could do in the interior of a building if it wanted to be super old-school, super pre-Vatican-II. It would be so easy to have all the things we know and love and have them all up there.

That’s not what they did. [They embraced] the secular and the educational and the arts. And I think this new version is going to also reflect the ideology of 2024. And that ideology is different. Not [different] in terms of good Americans and good Catholics and all that, and not in terms of respect for the past, but there are different things that we respect now and pay homage to.

And I hope that still comes through in the renovation. I’m sure it will. I’m sure it’s going to be so gorgeous that it’s going to be this great paying of homage to the past. When it was done in 1894, it was future-focused. And now, of course, in a way, with its restoration, any restoration, there’s a past-focus. You’re going back to your origins and saying, this is who we were. Look what we did back then, and we can do more going forward. But we did this back then, wasn’t it great? And I think that’s an interesting shift. That’s kind of important.

This interview by managing editor John Nagy has been edited for length and clarity.