- 11th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- Schaal Prize: “’Slife," Matthew Kane ’14

- 2nd Place: “These Are the Ways We Live," Kathleen Kollman Birch ’17, ’19MGA

- Honorable Mention: “Sehnsucht," Charles Kenney ’20

- Honorable Mention: “Life is One Big Toothbrush Party," Libby Garcia ’16

On the summer afternoon of my first full day in Dublin, I walked down the street from my shoebox apartment to a bookstore that specialized in “Irish interest titles.” I selected an edition — Penguin Modern Classics — and handed it to the middle-aged man behind the counter. He addressed me in the low, lilting register that I would delight in hearing throughout my seven-week stay and only become moderately better attuned to receiving. I asked him twice to repeat himself, then it clicked. He had asked, “You’re going for it?”

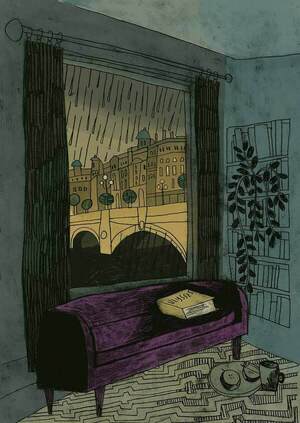

I did the math on my phone. Nine hundred thirty-three pages at a pace of 30 pages a day would total 31 days, with an extra push on the last. An hour, give or take, every day for a month. All told, not much longer than a day in the life. So I sat down in the purple, ergonomically impotent lounge chair that was all my apartment had to offer and opened to “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan” coming from the stairhead and into my life again.

It wasn’t the first time I’d “gone for it.” Shortly after graduating, I moved into my first post-college apartment, not far from my childhood home in Seattle, picked up James Joyce’s Ulysses and soon set it back down. My heart wasn’t in it, so I returned it to the library, and in the intervening years I never opened it again.

Until recently, those years passed at the same company and in a string of different residences all within the city limits. I nursed a mostly secret and intermittently explored interest in personal writing but had turned away from my stories for a different and more painful reason than I had turned away from Ulysses: There wasn’t any heart in them.

Meanwhile I read through more accessible titles, including Joyce’s Dubliners and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, and found a pulsing personal mantra in the latter’s closing prayer: that I might learn “what the heart is and what it feels. Amen.” What moved me was a sense of how much more there was to learn. I wanted my life to be an answer to that prayer.

In large part, though, I gauged my 20s by alternative metrics. More than anything, I measured my comparative position, the distance between the present and my half-imagined future. To borrow a Joyce-ism, I was “almosting it,” summoning a future that fell away around the edges, and so waiting for something, someone else’s expert hand, to lift me from the tight, inert tangle of reality and set me in the clearing of my undercooked dreams. I wanted to write, but didn’t set aside the time for it; to find a loving relationship, but didn’t know where to look; to be a dad one day, but that seemed so far away.

A few years ago, in a dream, I took a small, tin-can rocket on a flight to an Airbnb across the galaxy. After landing at the rental house, my host welcomed me inside in a language I didn’t recognize and then left me there alone. I wandered aimlessly, until I stumbled on a dimly lit room where a baby sat quietly, waiting, at the table.

July and August in Dublin were unseasonably wet. I read in the evenings, tracked Bloom’s peripatetic progress on Google Maps, and walked or ran in the rain along some of the same streets, alongside Dubliners not dissimilar to those depicted by Joyce haunting pubs, shops and cemeteries in 1904. I loved Phoenix Park, the view from Sandymount Beach, the way the darkest clouds could form in the bluest of skies.

I didn’t love every chapter of Ulysses. Some 30-page sessions felt like century-long slogs. When I read the introduction after finishing the book, several of the plot points it mentioned were news to me. But I got what I came for: the soft, beating heart of it, the blue on the otherwise dark, cloudy page.

Those are the moments I look for in literature, when you’re given a glimpse into the heart and humanity, and when you swell with that incredible feeling of what it’s like to be alive, to feel love and a sense of connection. In Ulysses, Bloom’s paternal affection shines through; in his moments of feeling toward Stephen and his daughter, in his painful remembrances of his own deceased father, and in the way that his son, Rudy, who died at 11 days old, is never very far from his mind. When he sees a young boy smoking a cigarette in the street, instead of passing judgment, Bloom imagines his life: “O let him! His life isn’t such a bed of roses! Waiting outside pubs to bring da home. Come home to ma, da.” With those lines, my heart swells for the boy, and for Bloom.

In Dublin, sore-backed, writing stories in the lounge chair, I heard a conversation outside the door of my unit that began with the question: “You know my dad died, did ya?”

A year earlier, I met a man whose infant son had died of cancer. He said his son was uninsured, and they did everything they could, but the baby didn’t make it, and his marriage didn’t last. I thought about him when Bloom thought about Rudy. A friend of mine told me he didn’t think he wanted kids. It wasn’t self-satisfying or apocalyptic thinking. He didn’t know if he could put someone else through the experience. Another friend of mine’s son is obsessed with things’ insides. “What’s the inside of a noodle look like?” he asked his father one night at dinner. I thought about my insides, what the heart is, in that moment.

Most moments of our lives don’t leave a lasting impression. The past is a fog with beams of light breaking through. If someone were to tell Joyce that Ulysses is a slog, a creationary marvel but, in its experience, kind of difficult, I’d imagine him like one of his characters, saying, “’Slife.” That’s life. You get what you get, what slices through. Life is hard. Life is beautiful. In Bloom’s conception, life is love. In Ulysses, Molly’s closing incantation is a thrill. Her “Yes” rings like magic — life is hard, but “I will.” It’s something I’ll hold onto, a reminder shining through, and, along with all the glimpses into warm, beating insides, it’s another of the many reasons why I’ll always turn to literature: its “eternal affirmation of the spirit of man.”

My last weekend in Dublin, the city was flooded with the greens, blues and golds of a Notre Dame wave, and from the streets of Temple Bar it passed on to the stadium, then back again, victorious, before drifting away. I left in its wake, looking back on those weeks and on the moments I wanted to experience again, either to relive their emotions or to right perceived wrongs. If I’d written that history, I’d go back and revise it, inserting something better — more loving — where it needed it. But life isn’t like that. Art is like life; it’s at its most brilliant and beguilingly affirmative when what it communicates and inspires in the moment is love.

For a little over a year now I’ve moved from place to place; those seven weeks in Dublin remain my longest stay in any of them. With September came another temporary city and, if anything, an only slightly clearer vision of my future. But it also brought an answer, a way of living in the moment, an opportunity in every instant to say yes to life and love. Nothing is more wasteful than almosting the present. Give more, go all in — “You’re going for it?” “Yes.”

I still hope someday to be a husband and a father. But I’m trying not to chase it or to measure my position. I’m measuring the moments — how much love is shining through?

I was living in Seattle, getting ready to leave town, and on a summer afternoon I took a run around the lake. As I started walking home, I saw a girl on her bike and her father, on a run, trailing 20 feet behind her.

He called, “Bella.”

She yelled, “What?”

He said, twice, “Please come talk to me.”

But she kept riding, shouting happily into the distance, “I can’t hear you!”

Matthew Kane’s essay won first place in this magazine’s 11th annual Young Alumni Essay Contest — the Schaal Prize, named for former managing editor Carol Schaal ’91M.A. Kane studied marketing and English at Notre Dame, has published multiple books on K-12 education and is working as a writer and editor in Seattle. Read the honorable mention winners at magazine.nd.edu/schaalprize.