More than a decade ago, when he was a graduate theology student working on, of all things, the creation of a planetarium show, Leonard DeLorenzo ’03, ’14Ph.D. carried his contemplations of the universe into daily Mass, where he had a kind of extrastellar epiphany.

He was thinking about that part of the presentation near the end, when the camera’s eye somehow slips through the outer temporal limits of what we 21st-century Earthlings are able to see via satellites, telescopes, computers and data imaging: the farthest boundaries of the universe.

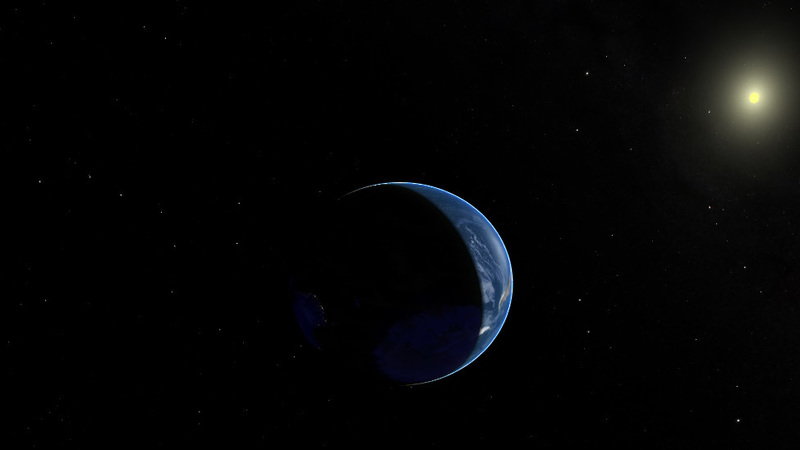

Certainly more stars and nebulae lie beyond, but it’s all so far from Earth that the light those heavenly bodies emanate hasn’t had enough billions of years to reach us yet. So, as our flying vantage-point zooms into the void, looking back toward the sum total of recordable light and time, that dark, uncharted realm appears on the planetarium dome as a vast blackness threatening to engulf the luminous aura that is our observable universe.

What DeLorenzo at prayer was beginning to see in that white circle of the universe’s light was an analogy to the Eucharist: “Everything, contained in one ‘small’ space, being given to you,” he says.

For the young theologian, that moment of rare perspective was about humility and the wisdom that comes from acknowledging our “astounding insignificance” in relation to “the unfathomable expanse of the cosmos.”

“Our significance comes only from the attention and care invested in us,” he adds today. “This is the mystery of creation and it is completed in the mystery of the Eucharist: the meaning of heaven and earth given to us under the unassuming appearance of bread and wine — in little space.”

Now the author of six books and academic director of Notre Dame Vision, a summer program of Catholic retreats for high school students, DeLorenzo was taking what in hindsight appears to be a prophetic interest in the relationship of science and religion. The New Atheists were in peak vogue at the time, renewing age-old arguments about the supposed incompatibility of science and religion, and they were making inroads among the faithful. Half a generation later, writes Chris Baglow, director of the Science and Religion Initiative at Notre Dame’s McGrath Institute for Church Life, 70 percent of college-age Catholics “see science and religion as locked in conflict, and say that the discoveries of modern science have not strengthened their faith.”

At Notre Dame, DeLorenzo was working with astronomer Phil Sakimoto, a former NASA administrator and education specialist, on “All Creation Gives Praise,” a tour of the universe guided by a dialogue between astronomer and theologian to be presented in the Digital Visualization Theater (DVT) at the Jordan Hall of Science. As the viewer soars through space, the scientist speaks established facts of cosmology and the scholar of holy being responds with reflections and prayers spoken in awe and wonder, drawing on Scripture and the writings of saints and others, from Augustine and Aquinas through Hildegard of Bingen and Catherine of Siena.

The total package presents two ways of knowing. Two sets of questions, observations, speculations, answers and then new questions: both lines of inquiry probing toward each other and toward the outer reaches of mystery.

As the program begins, you recline in a meadow looking up at the constellations of the night sky. Soon, imaginary lines connect those stars in patterns the ancients devised to make sense of what they saw. But then you ascend for the space journey, turning to look at Earth as you sail backwards and away from its surface, briefly appreciating the thin blue line of its fragile atmosphere.

“As we go,” Sakimoto intones, “everything you will see is real . . . what you would see if you really could travel through space.”

Now you are hurtling past the moon, some 250,000 miles away; now past the piercing sun as the orbits of the planets of our solar system appear. Distances on this space odyssey quickly outstrip your ability to comprehend them. Outside our solar system, you watch the constellations and their fictive lines stretch and compress, their patterns now meaningless from this new, mobile and impossibly remote perspective. Before long — our sun quietly disappearing from view — you reach the “radiosphere,” the full extent to which, over a century, our radio and TV signals have unwittingly “sent word of our existence out into space.”

Here’s how scientist and theologian meditate on that moment.

Sakimoto: Ironically, as cable TV and direct-broadcast satellites replace open-air broadcasts, the signals we are sending out into space will cease. It is as if, upon entering the age of technology, we cried out to the galaxy with a burst of signals, only to soon fall into a deep and eternal silence.

DeLorenzo (quoting Psalm 77 and the French philosopher Simone Weil): I cry aloud to God. I cry to God to hear me, but my voice only travels so far. The distance is too far. I cannot reach you, Lord. And so you reach down for me. You call back to me. You speak here from beyond the limits of my voice, and your voice pierces the orb of my frustrated limitations. . . .

At that point, your planetarium journey is only just beginning. By the end, DeLorenzo says, the Earth you return to looks different from the one you left behind. The attentive viewer should have a better understanding of “what a mature Catholic faith looks like,” one reliant on both religious wisdom and scientific observation in its search for truth.

“The astronomy stuff you saw, a lot of places can do that,” Sakimoto adds, noting that the datasets the show uses were created by the American Museum of Natural History for adaptive reuse. “But Lenny really made it into something special.”

Since the first public presentation of “All Creation Gives Praise” in 2007, its co-creators have given their work four major overhauls and presented it in person dozens of times to thousands of people, mostly at the DVT: high school science and theology classes, ND Vision retreatants, teachers and professional and academic astronomers attending a planetarium conference.

A few years ago, they recorded it with the support of the DVT and the McGrath Institute, getting vocal coaching and production help from campus professionals and incorporating the music of the Notre Dame Folk Choir and singer-songwriter Danielle Rose Hesley ’02. And in 2017, more than 100,000 people saw a 10-minute distillation of it — translated into Russian, Kazakh, Chinese and Italian — inside the Vatican’s exhibit at an international energy exposition in Kazakhstan.

Sakimoto, who traveled to the central Asian nation to provide the show’s technical support, tells the story of a visitor from “an oil nation” who exclaimed on his way out that the show was “the most amazing thing he’d ever seen.” A Catholic priest who heard this remark handed the man a copy of Laudato Si’, Pope Francis’ 2015 encyclical on the ecological crisis. The man returned the next day with similarly effusive gratitude for “the greatest book I’ve ever read.”

The American Catholic laity have proven to be a tougher audience for that papal teaching, Chris Baglow says, due in part to a widespread “mistrust of science based on assumptions the Church doesn’t share.” Too often, DeLorenzo adds, high school theology textbooks haven’t helped, failing to present scientific information in a serious way. Thus the need for educational tools like “All Creation Gives Praise,” which Baglow hopes to take on the road in his program’s core effort to better prepare high school teachers to help students understand the parameters of — and the questions asked by — both disciplines.

“Moving beyond what we already know is risky,” a woman’s voice says in the show’s introductory narration, “because discovery is the herald for change.

“Our presence here is an act of trust because our exploration may prompt us to ask not just ‘what?’ but ‘why?’ And our response entails a decision.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine. To arrange a showing of “All Creation Gives Praise” at the DVT or an affiliated planetarium, contact Leonard DeLorenzo at ldeloren@nd.edu or Phil Sakimoto at psakimot@nd.edu.