Kierkegaard’s idea kept coming up in conversation: Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards.

Seven 1973 graduates wrote Notre Dame Magazine essays as college seniors. The world, the campus and the student body — all male for three of their four years, with Saint Mary’s College panty raids still an active tradition — have changed immeasurably since then: Paul Dziedzic, who lost to Robert “King” Kersten ’74 and his feline running mate in the 1972 race for student body president, once hitchhiked from Chicago home to Washington state. These days, students use their thumbs to hail rides technologically.

In other ways, echoes of that era persist. Amid a cacophony of intractable conflict, it’s helpful, if a little disheartening, to remember that ours is not a uniquely divisive time. That protests over Vietnam and civil rights brought people into angry, even violent opposition. That it’s human nature, not a generational thing, to demand to be heard while tuning out differing views. As John Walsh described the campus atmosphere in his senior-year essay, “everyone was lining up on either side of issues, and debates raged constantly.” Noting the persistent rose-colored impressions of Notre Dame that belied his more complicated experience, James Fanto wrote, “people ignore anything which conflicts with their vision.”

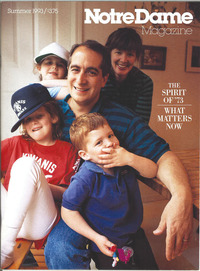

When the magazine caught up with them in 1993, the 20-year alumni were in forward motion, midlife, midcareer, with young kids at home. Old enough by then to have the perspective to reflect but very much “eyes front,” focused on everyday demands.

They can look back now. All seven are active in their early 70s, either with ongoing careers or retirement vocations — to say nothing of the 20-plus grandchildren among them. With a moment to reminisce, they find a retrospective clarity in their adult lives. They recall no such lucidity as events unfolded in real time.

That brought Kierkegaard to mind. And, for Walsh, a passage from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding”:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Gray matters

As a Notre Dame senior, Paul Dziedzic ’73 received a card from a friend with a quote that began, “Only the brave dare look upon the gray — upon the things which cannot be explained easily.” Another read, “He made them look within, and decide for themselves.”

Those sentiments resonated enough for Dziedzic to quote them in his 1973 Notre Dame Magazine essay, but their enduring relevance would be revealed only with the passing years. Through periods of intense introspection during personal and professional changes, Dziedzic has spent a lot of time looking within, upon the gray — and encouraging others to do the same.

During a career spent in and around state government, he came to understand that his greatest contribution would not be in policy expertise or counsel provided from a particular political perspective. Rather, it would be his capacity for convening people of conflicting interests and guiding them toward productive dialogue.

Returning to Washington state after a postgraduate year in Chicago, he worked as an intern on disability rights, later becoming executive director of a governor’s council on the issue. Long before the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act, one modest goal — to create wheelchair-accessible curb cuts at street corners around the state capitol — prompted concerns from the blind. The small drop from curb to street provided them a vital indicator when they were about to step off a sidewalk.

A moratorium on the curb cuts bought time to rectify the impasse. “Both viewpoints had legitimacy,” Dziedzic says. “So we get together and say, ‘Is there a solution that will meet both needs?’”

The cuts could work, the parties determined, if they included ridges to alert the blind. Making the cuts a distinct color would further assist low-vision people.

“Not everything is as easy as that,” Dziedzic says, but the principle applies to thornier disputes. If people with opposing positions have both an opportunity to be heard and an openness to listening, conflicts can be resolved with mutual benefits. In Dziedzic’s view, everyone — very much including leaders with government-vested authority like he had — must cast off the pejorative sense of the phrase, “What do they know?” and ask it with an open mind.

When he did vocational rehabilitation training with Native Americans in the state, Dziedzic attended a conference where he heard a Navajo joke: “How many people are there in a Navajo family? Five — mother, father, brother, sister and researcher.” Concerned that he might represent the punch line, he approached a tribal leader he worked with who told him, “No, Paul, you came in to learn, not just to teach.” That was heartening reassurance that he had heeded a mantra he had learned from people with disabilities: “Nothing about us without us.”

In the 1980s, he took on the new position of special assistant to the governor for substance abuse issues. “Dziedzic was a rising star in the world of Washington state politics,” Notre Dame Magazine reported in 1993, already in the past tense even then. His professional success was taking a toll on his availability as a parent.

“The kids were at the age they were in starting soccer and all that sort of stuff,” he says today, and his job demanded too much time away from the precious moments of those fleeting years.

He stepped back. Multiple part-time roles, like a temporary post running a University of Seattle leadership program, allowed the needed flexibility. State government opportunities arose as well. His policy portfolio ranged from fetal-alcohol syndrome to traumatic brain injury to management of public lands.

The subject matter was beside the point. “I realized that, jobs I’d had, the consistent thing that was me in it was that I helped people figure out how to get something done together,” Dziedzic says. “I literally had the thought, ‘It does not matter what it is,’ because my role is in helping that happen.”

Today he directs a leadership institute at the University of Washington’s Center for Continuing Education in Rehabilitation. He also facilitates meetings through his consultancy, as a “stagehand” helping organizations define and achieve their objectives. It’s a happy place in life, buoyed by a second marriage and four grandsons — “grandguys” — who live nearby, allowing him to be a regular at ballgames and school pickups. But that happiness is hard-won.

Around the time Dziedzic scaled back at work in the 1990s, his first marriage ended, sending him into a tailspin. He began to grasp with dismay that, as anything other than a husband and father to his three children, he didn’t know himself. “I had identified myself so much with the two roles,” he says, “that who I was had gotten lost.”

One evening on a walk, he wondered, “Who am I?” The question conjured an image of a black hole. With fatherhood still integral to his life after the divorce, Dziedzic set out to find a comprehensive answer. On free weekends, he would go off without a plan, choosing everything in the moment down to the direction of his next turn. “It was forcing myself to say, ‘You are there. What you want to do, what you care about, what you like actually matters,’” he says.

New friendships and romantic relationships enriched his self-understanding. Among other revelations, “I learned I was a flirt,” Dziedzic says, mining his memory for the discoveries of that mid-40s return to single life. The more he looked within — finding his own happiness first, rather than expecting others to be the fount of his contentment — the stronger his bonds with friends and loved ones became.

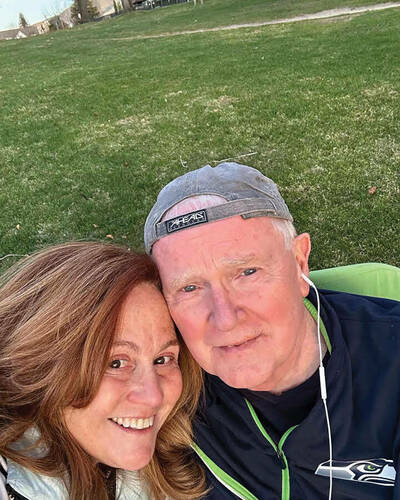

The deepest bond has been with Suzy, his wife of five years and companion of more than nine — 120 months, to be exact, measured by the monthly cards they give each other. They both still work at the university center where their romance began.

Sitting under the pergola in his backyard — “one of my favorite spots on earth” — Dziedzic hoists the couple’s boisterous puppy, Coco, onto his lap. Questions once clouded his identity, but it’s clear he’s answered them to his satisfaction.

Not what he was counting on

A whiteboard on the wall of the Abowd family’s kitchen in Ithaca, New York, featured the fundamental theorem of calculus. It stayed there for years until the room was remodeled.

“Because our children thought it was hilarious,” says Janet Abowd ’74.

“It’s a thing of beauty,” John Abowd ’73 interjects, sounding like he must have at the dinner table: an insistent father trying to bequeath his enthusiasm for the intricacies of economics.

That enthusiasm endures, but it had to survive intense and unforeseen pressures over the past few years. After a long career as a Cornell University economics professor, Abowd moved to Washington, D.C., to become chief scientist for the U.S. Census Bureau in 2016. A lot happened between then and the distribution of the 2020 census.

First, a new presidential administration upended Abowd’s responsibilities, then a pandemic compromised the bureau’s vast fieldwork operation. None of this was conducive to the complex, meticulous task of national enumeration that the Constitution requires — and that Abowd had been eager to lead. Having worked with the bureau since 1998, he was well-versed in the methods of producing an accurate count of the American populace for the high-profile purposes of allocating political representation and federal funds, among other things.

The job Abowd signed up for was nearly consumed by political calculation and legal challenges. In December 2017, the Census Bureau received a formal request to include a citizenship question on the 2020 census. Abowd opposed the idea. His stance was statistical and financial.

In memos to Wilbur Ross, whose purview as Commerce secretary included the census, Abowd argued that the change would be costly to implement at such a late stage in the census process and likely exacerbate a predicted undercount of immigrants, many of whom would fear revealing their status. Existing federal data could answer the question, he wrote, without compromising the accuracy of the census.

After Ross ordered the question’s inclusion, lawsuits challenging it proliferated from states, municipalities and nonprofits. Abowd became a central figure in the legal controversy, giving four days of depositions and seven days of testimony in federal courts — forced to defend a position he didn’t support.

“The exchanges reveal Abowd as a cautious and technically sophisticated academic who, while taking a clear stand against adding a citizenship question, was tactful in criticizing fellow scholars,” according to Government Executive, a publication that reports on federal agency leadership. “And he was respectful of the limits on civil servants when they’re up against political appointees higher in the chain of command.”

The ordeal took a toll. Government Executive added that Abowd’s hundreds of pages of testimony depict “a bureaucrat stretched to the point of exhaustion.” The New York Times Magazine described him as near tears on the witness stand, “a rare moment of genuine human drama in the trial, and perhaps in the modern history of the census.”

And a rare moment of emotional expression for Abowd himself. “I never think of you talking about how you feel about life and about how things have changed or what has brought you satisfaction,” Janet Abowd says from across the living room in their D.C. apartment.

To her, John is a “honey badger,” unrelenting in duty. Even in the throes of the census tumult, when he’d declare he was going to quit, she knew he never would. In fact, he stayed years longer than planned to steer the process through further straits, not retiring until this July 1.

In addition to other complications, the 2020 census required major new confidentiality protections to safeguard the glut of data from misuse in the information age. The implementation required compromises which ensured that neither privacy advocates nor data-quality purists would be satisfied.

“That has made me the . . .”

“I believe the term is bête noire,” Janet offers.

“Yeah, bête noire works,” John says. “‘Whipping boy’ is where I was headed.”

John Abowd and his team feel confident they fulfilled their mandate. And though criticism might have been loud, “I think the majority of the stakeholders are quite happy with being able to deliver data from a census conducted during a pandemic,” he says.

He plans to recount his census experience in a book and has a constitutional reluctance to call himself retired. By last April, though, he had accepted that the term would soon apply to him.

“I am using it in the technical sense now,” he says. “You are retired if you don’t intend to work for pay again. That’s the economic definition of being retired.”

A looser meaning captures the joy he intends to take in time spent with his four grandchildren, three of whom live in the D.C. area.

“The personal surprise is how much fun grandchildren are,” Abowd says. “Intellectually, I understood that they were consumption and not investment, so from that point of view, I’m not surprised, but it’s just been a delight.”

Reverse engineer

John Walsh ’73 “never recovered from Africa.” By that he means that the appeal of the continent where he spent two years teaching as a Peace Corps volunteer has stayed with him ever since.

Walsh and his wife, Kate ’79, live in Catonsville, Maryland, near the Beltway region where John has spent his whole life. They also own a beach house in South Africa — an Airbnb they call “Walsh Hall,” not only after their surname but also to honor the dorm where they each lived.

In their nascent retirements they spend time in South Africa visiting their daughter, the second oldest of their four children. She went on a volunteer trip, “met a sugarcane farmer, and now she’s a sugarcane farmer” with twin 7-year-old girls, John Walsh says — ample excuse to return to a part of the world that captivates him. On each visit to Africa, the couple tries to add a new country to their itinerary.

Life allows for more personal exploration now, for more time devoted to their five grandchildren and “nonprofit, worthy things, as opposed to the things that pay you,” Walsh says. He works with Afghan refugees and leads the finance committee on the board of Baltimore’s Saint Frances Academy, the oldest Black Catholic school in the United States.

“Mostly retired,” John Walsh still consults occasionally for McKinsey and Company, a byproduct of his unlikely service as acting comptroller of the currency — the head of the independent bureau in the U.S. Treasury Department that supervises national banks. His highest-profile role in decades of government work, the position represented the culmination of a twisty career path that offered Walsh a view of Washington’s inner workings.

Although aligned with the Republican Party, he found the work interesting in a nonpartisan, even scientific way. “I loved it like an engineer would love it, just the machinery of it,” he says. “You know, ‘When you push this, what moved?’ That kind of cause and effect.”

That’s about the only link between his undergraduate education and his professional life. With a romantic notion of what it meant to be a scientist, Walsh had enrolled at Notre Dame in 1968 as a physics major. His first discovery was that the subject was not for him.

The appeal of science and math remained, but he wanted to broaden the scope of his studies, which led him to mechanical engineering and the liberal arts. “I wanted to study as much stuff as possible,” he says, “to foreclose as few opportunities as possible.”

After the Peace Corps, Walsh had to choose among the options he had kept open. Teaching, as he had done in Ghana, held little appeal. An “absolutely horrible” job in radio — he had been the WSND station manager on campus — made clear that broadcasting wasn’t for him either. Within three weeks, Walsh says, “I was like, ‘What’s the minimum time I can be here and not look like a total idiot?’”

Graduate school offered an escape hatch. He focused on international development, a vestige of his Peace Corps experience, at Harvard’s Kennedy School. That background took Walsh around the world and granted him access to rooms where “it” happened in Washington.

Walsh spent six years in the Office of Management and Budget, bridging the Carter and Reagan administrations as an analyst focused on international aid in Asia, visiting places like Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines. To move into policy work, he joined the Treasury department. “More of an economic and diplomatic kind of thing,” Walsh says, “which was the change that I wanted to make.”

That led in 1986 to a staff position on the Senate banking committee under ranking member John Heinz, a Pennsylvania Republican. The job taught him the differences between work in the executive and legislative branches.

“When I was working at the Treasury, you’d have a tiny job in a big machine, but if you could work away at your screw and turn that cog a couple of degrees, something actually happened,” Walsh says. By contrast, “You could go to Congress and write speeches and introduce bills and everything till the cows come home” with nothing to show for it.

The engineer’s fascination remained, but tragedy intervened. Heinz was killed in a 1991 plane crash, and as the committee leadership changed, Walsh eventually moved on.

He spent 10 years with the Group of 30 — an independent organization of international financiers, academics and government officials that studies global economic and financial issues — as executive director. “A grand title for a job that that had a certain stature by virtue of this group of people you’re associated with and the reports that were done,” Walsh says, hastening to add that, despite what people often presumed, he was decidedly not one of the 30.

In 2005, John Dugan, a friend and former colleague, was appointed to Treasury as comptroller of the currency. He asked Walsh to be his chief of staff.

Dugan’s five-year term ended in 2010, just as implementation began for the Dodd-Frank Act, which overhauled the country’s financial regulations in the wake of the Great Recession. Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, another longtime acquaintance and previous member of the Group of 30, asked Walsh to step in as acting head of the agency.

“It was not entirely popular to take somebody from the previous administration and ask them to be the ‘acting,’ as opposed to putting a true believer in there,” says Walsh, who marvels at the continuity on the handling of the financial crisis between the Bush and Obama administrations.

For the next two years, he oversaw the fraught work in the comptroller’s office as the new regulations under Dodd-Frank went into effect. On the first anniversary of the act’s passage, Walsh had his only audience with a president, meeting with Barack Obama to discuss the implementation. “I found that a treat,” he says, “even though I was supposed to be from the other side.”

Walsh’s winding journey makes sense to him only in retrospect, though from the outside it may look like the consequence of a meticulous plan.

“When I was talking to McKinsey about working for them . . . someone said, ‘Your résumé, it makes so much sense, you can just trace it from one end to the other,’” Walsh says. “I assured them it didn’t make nearly so much sense at the time.”

Live and learn

James Fanto ’73 hasn’t kept in close touch with his old friend and fellow Scholastic editor Greg Stidham ’73, but they have fond memories of each other. Stidham, for his part, considers Fanto “one of the smartest guys I’ve ever known.”

That checks out. Fanto holds both a doctorate in comparative literature from the University of Michigan and a law degree — first in his class at the University of Pennsylvania. He’s been a professor for 30 years at Brooklyn Law School. The preceding two decades of Fanto’s life, before he joined the Brooklyn faculty, read like a period piece about a restless intellect following whims of curiosity, collecting advanced degrees, accumulating professional success. Caen, France; Ann Arbor; Oxford, Ohio; Philadelphia; Paris.

Fanto sounds almost sheepish about it — not regretful, but as if he’s considering the implications of his choices to this day. “Maybe I could have done better if I had been more focused back in the day,” he says, asking himself in retrospect, “Why did I do all that stuff?”

The financial law Fanto went on to practice and teach was nowhere on his radar as an undergraduate English major. In a sense, even English wasn’t front of mind as he headed off after graduation.

“I got interested in French at Notre Dame even though I had never studied. I took a few courses,” Fanto says. “So I said — now, was this a wise thing to do? — I said, ‘Well, I want to go to France for a year.’”

Off he went. He could enroll in a school for free to study the language. With money from jobs at Notre Dame, the $200 a month to live there was no problem. Meals cost around 25 cents.

After that yearlong detour, a doctorate in comparative literature seemed logical enough. He spent the better part of a decade immersed in English, French, Greek and Latin texts and taught for a year at Miami University in Ohio.

At that point, the prospect of climbing an academic career ladder, hustling for tenure, felt “limiting.” And so, with doctoral work left to complete, he decamped for law school in 1982.

After thriving there, Fanto landed clerkships with a district court judge and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun. A job practicing international business law with a D.C. firm followed, along with the matter of finishing that doctorate. “I had written everything,” he says. “Just had to go back and defend it.”

Fanto’s wife, Mary Conway, worked for the same law firm and her expertise in tax law was needed back in Paris. Fanto’s facility with the language only sweetened the prospect for their employer, so the couple went for a year that turned into four. Their son, Paul, now 30 with a recent doctorate in nuclear physics, was born there. Eleanor, 28, a nurse at Boston Children’s Hospital now pursuing her own advanced degree, came along after they relocated to New York.

Thirty years ago, when Notre Dame Magazine last caught up with the Class of ’73 essayists, the family was on the cusp of returning to the States, and Fanto was considering his next move. His only condition was that it be “interesting,” conscious that middle age had its perils as he entered his 40s and fatherhood around the same time. People “start getting bored, and whether they have said it or not, the challenges are gone,” he said then. “You need something new.”

Teaching international business became Fanto’s new challenge, his expertise refining over time into a specialty in compliance — how companies adhere to the law and industry ethics. “With all our corporate scandals and financial scandals,” he says today, compliance has been a growth area in legal education during his Brooklyn tenure

Not the nostalgic type — Fanto’s senior-year essay expressed “fear” of lapsing into “that irritatingly sentimental emotion” — he looks back with a discerning eye. No accomplishment receives his categorical approval.

“I wonder about the Ph.D. sometimes,” he says. “I spent a lot of time on that, you know, so should I have. . . ? But you get some gains, and the gains are sometimes hard to understand — where they’ll lead.”

The gains that served him well include applying a literature student’s close-reading skills to the technicalities of business law. To say nothing of the intangible satisfaction in the journey.

He sacrificed neither intellectual excitement nor professional achievement along the way. If he’s sensitive to how his career differs from the norm, others see it as a natural extension of his nimble mind and oscillating curiosity.

“I feel pretty sure he wanted to do all of it,” Fanto’s old friend Stidham says, “and by God he did.”

His own words

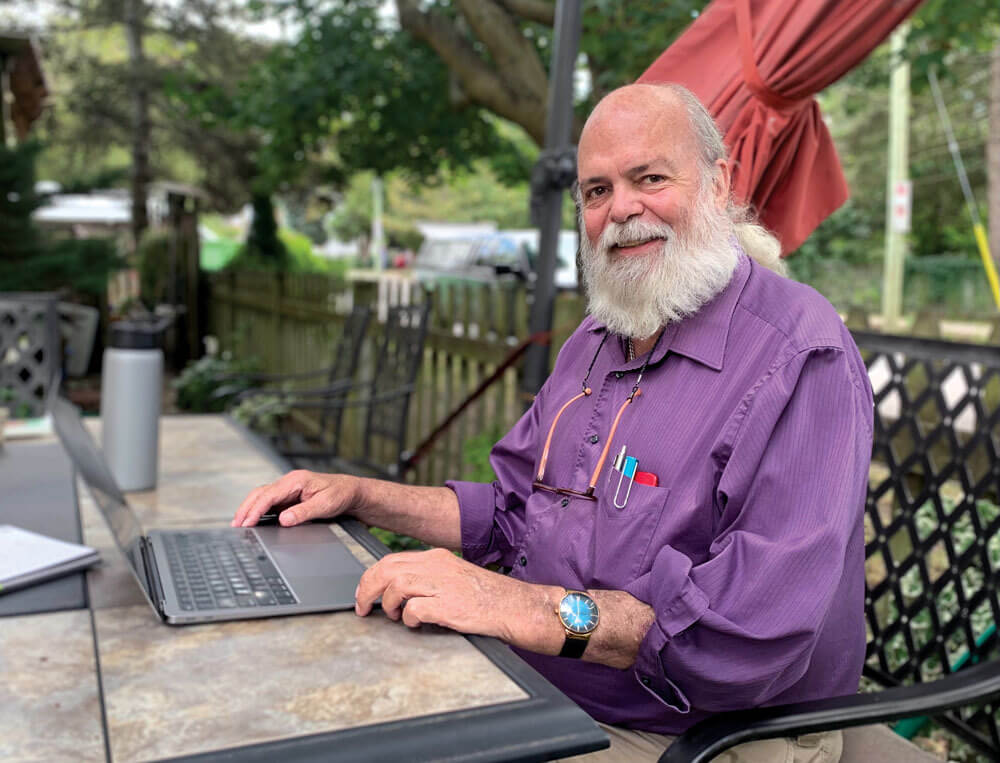

Greg Stidham ’73 posts poems on a tree outside his house in Kingston, Ontario. He flanks the verse with New Yorker cartoons, figuring the humor might lure more passersby to stop and read.

A retired pediatric intensive care physician, Stidham “repressed another self” during his medical career, he writes in the introduction to his 2021 poetry collection, Doctoring in Nicaragua. In his poems, which do not go on the tree, and a memoir, Blessings and Sudden Intimacies, he liberates the writer inside him.

Stidham has taken nourishment from reading and writing ever since Brother Joseph Chvala, CSC, ’54, ’66M.A., instilled a hunger for language at St. Edward High School outside Cleveland. With no less an appetite for medical school, Stidham came to Notre Dame for the Arts and Letters preprofessional program, intending to fill up on all the literature he could read as an undergrad. Turns out, that buffet was insufficient.

When an adviser said he didn’t have enough science on his schedule, Stidham replied, “OK, fine,” and left the pre-med program. “I took all the English classes I wanted,” he says, “and used my electives to take the science classes.”

Still determined to become a doctor, he knew he was taking a risk with his post-graduation options, but he never doubted his academic redirection. “I was crazy about literature, and I was crazy about learning how to write,” he says. “And it’s like, ‘You’re not stopping me.’”

The choice didn’t obstruct his professional ambition. A medical degree from the University of Toledo and training in pediatric critical care at Johns Hopkins led him to Le Bonheur Children’s Medical Center in Memphis, where he spent most of his career.

The connective tissue between books and medicine lies in the power of each to nurture and sustain human life. In 1973, Stidham wrote that the purpose of a Notre Dame education is to become a compassionate person who lightens others’ burdens: “That is all that matters — the possibility of making life a little less difficult for someone else. And Notre Dame, finally, will have mattered only if it has made that possibility a little more tangible for each of us.”

Stidham always felt compelled to support suffering people. During his undergraduate summers, he worked in the psychiatric unit at a Case Western Reserve University hospital, attending patients with extreme mental illness. They seemed worse off even than those in severe physical distress. “That was the most profound experience of my life up to that point,” Stidham says, “and so I actually thought I wanted to be a shrink.”

Then a pediatric residency brought him to the bedsides of children in intensive care. “I would just hang out there,” he says, drawn by the opportunity to practice medicine in its fullest sense. “Not just the biochemistry and the anatomy and the physiology, but the whole other part,” the empathy that children in dire conditions and their families need.

Creating emotional bonds only made the job harder. In his Memphis hospital, the ICU admitted over 100 children a month. Cruel fate and cold statistics meant six or seven of them would die.

“It’s sad. And sometimes it just plain sucks, right?” Stidham says. “I mean, I would lose a patient that I cared for in a special way, and my sons will tell you that they remember me coming home and pounding my fist on the table. And they’ve seen me cry.”

Across their kitchen table, Stidham’s wife, Pam, points out what an inspiring example that was. “Tim’s doing the same thing right now,” she says of his younger son, also a pediatric ICU doctor, “so you must have conveyed the right message.”

With elder son Chris teaching high school English, it’s as if each of Stidham’s sons inherited half of what their father calls his medical-literary “multiple personality disorder.”

Chris married a woman who grew up in Kingston. Charmed by the town of 135,000 about three hours east of Toronto, Greg and Pam Stidham decided to move there. They planned to stay three years until Stidham retired, then settle in Colorado, where they have a house. When that time came in 2012, neither wanted to leave.

Tim had played a hand in bringing his father and Pam together. Not long before he went away to college, Tim came home with a King Shepherd puppy, a gift from a friend’s mother, who bred the dogs. Stidham, a divorced single father soon to occupy an empty nest, said there was no way he could care for a dog with his hospital schedule. Tim promised to take him back “tomorrow.”

“‘Tomorrow’ we’re at the pet store getting the training kennel and 50 pounds of dog food,” Stidham says, “and he and I were inseparable for 12 years.”

That was Smokey. Pam, who had recently moved into Stidham’s neighborhood, was out with her dog, Lakota, one day as Tim walked Smokey. Son and dog made Pam’s acquaintance first. “That’s why, when you were walking him later,” Pam says to Greg, “he already knew Lakota.”

The couple now has two rescue dogs, Dexter and Bear, that need no small amount of care. Stidham, diagnosed decades ago with multiple sclerosis, has struggles of his own, but he brushes them off. “I don’t know if anybody has had a more benign case than I’ve had,” he says. Just some muscle weakness in his legs and a slight shuffle that could be chalked up to age if you didn’t know of his condition.

In retirement, Stidham volunteers as a grief counselor. That continues work he’s done with families whose children had died or who were adjusting to the life-altering effects of illness or injury, extending it now to people who have suffered any kind of loss.

“The two things that sustain me are that and writing, and the reading that goes along with writing,” Stidham says. “That’s the opportunity I have for a second life.”

Keeping the faith

During one of his many visits to Lithuania, Linas Sidrys ’73 was smuggling a stash of Bibles and other spiritual contraband. With the small, European country then under the oppressive rule of Soviet premier Leonid Brezhnev, Sidrys needed to create a diversion to slip the clandestine religious goods through customs. During a layover in Helsinki, Finland, he picked up a copy of Playboy magazine and put it at the top of his suitcase so the border agents couldn’t miss it.

Upon his arrival in Leningrad — on the roundabout itinerary to Lithuania that was required at the time — the magazine caused even more of a stir than Sidrys had imagined. Officials herded around for a close inspection, the cargo he cared about drawing no notice in comparison to the Playboy.

“Here’s the embarrassing part,” Sidrys says. “They said, ‘Well, you can take it in, but only if it’s for your personal use.’”

That posed a dilemma. Could he sign the form affirming the “personal use” stipulation about a magazine that offended his moral sensibilities? A lie wouldn’t sit well on his conscience. Under the circumstances, he had little choice, but he pondered the ethical tension — not unlike those posed during his undergraduate philosophy discussions with professors Joe Evans and Ralph McInerny — and reasoned that he had an honest self-justification.

I’m using it to distract you, Sidrys thought, so, yes, it’s for my personal use.

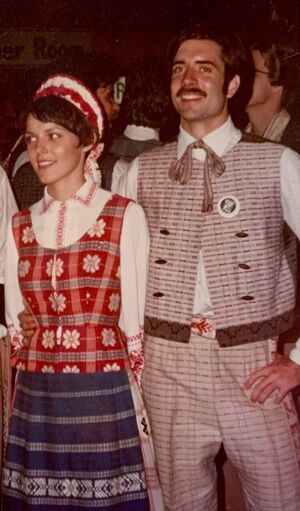

On he went to his parents’ homeland, the wellspring of the faith, culture and language that he and his eight siblings, along with his wife, Rima, and their eight children, have been immersed in all their lives. Thriving Lithuanian communities in and around Chicago, where Sidrys has spent his life, nurtured the family’s deep roots in the old country. He and his siblings, and his wife and children, all speak fluent Lithuanian, often the language of their conversations.

An ophthalmologist, Sidrys once made regular medical missions to Lithuania, inspired in part by the example of Thomas Dooley ’48, the Navy doctor whose statue at the Grotto commemorates his service to refugees and the poor in Southeast Asia. Sidrys’ work in Lithuania began when he was a student at the University of Chicago’s medical school and became the first American to intern in the Soviet Union.

Chicago’s medical students traditionally spent a quarter abroad, but Sidrys had been denied entry into Lithuania twice. In 1977, the school’s dean intervened with a friend who happened to be the head of the Moscow Academy of Sciences.

“Old Jewish guys, you know?” Sidrys says. “So I get a call Christmas Eve. ‘Be here in five days.’”

His experience as a student was restricted to attending lectures — hospitals were off-limits to him then — under constant, unconcealed KGB surveillance. To travel between cities required official approval, a chauffeur and the KGB tail, who spent six hours on one trip prodding Sidrys with propaganda. One day, Sidrys treated his shadow to coffee.

A big takeaway at the time, reaffirmed on subsequent mission trips into the early 1990s, was that Lithuania had well-trained doctors who were bereft of the most basic medical supplies. The deprivation he observed throughout the country assured him that Soviet Union could not survive, but also underscored the value of the assistance he could provide — medications and instruments and his own surgical expertise.

How bad was it? Sidrys drops a nonchalant anecdote about a bomb that knocked out power at the hospital while he operated on a patient.

“A bomb?” Rima asks.

“Yeah.”

“Whoa. I didn’t know that. You never told me that.”

The attack did not target the hospital, he explains. Damage to an electrical facility caused the outage, forcing the medical staff to move the patient to another city to complete the procedure.

Sidrys also tended to everyday and eternal needs that the Soviets had choked off from the Lithuanian people, providing food and clothing and those illegal imports of the Catholic faith, which endured in the country despite the Communist yoke.

“We used to joke that if we couldn’t find something at home, then Dad sent it to Lithuania,” his youngest daughter, Žiba, said in a Lithuanian public media report that referred to Sidrys as “the famous ophthalmologist.”

“One time he went there with, like, I don’t know, four Army bags full,” Rima says, “and the Lithuanian neurosurgeon that was at our house helping you pack said that they should build a monument.”

They kind of did. Valdas Adamkus, a longtime administrator in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency who lived not far from Sidrys in suburban Chicago, later became the second president of newly independent Lithuania. In 2009, Adamkus presented Sidrys with one of the country’s highest honors in recognition of his service.

“I’m a knight,” Sidrys says with a sheepish shrug.

A framed photo commemorates the occasion, but Sidrys has oriented his adult life around other titles — husband, father, doctor. As the family grew to eight children and the Iron Curtain lifted in Eastern Europe, he cut back his visits to Lithuania. With work and the kids, Sidrys was plenty busy at home.

He maintained multiple ophthalmology practices — in his native Streator, Illinois, about 100 miles from Chicago; in suburban Palos Hills, where he and Rima have lived for four decades; and in the city. Still working today, he’s down to just one office and four days a week instead of his previous six, including Saturdays.

“I said, ‘You’re missing all the weddings and funerals of our friends and their parents,’” she says. “Seriously. That’s a very big social day, especially for the Lithuanians. There’s always weddings, always funerals and cultural events on Saturdays.”

A family wedding recently brought 15 of their going-on-20 grandchildren to town. Now, as in their child-rearing years, the couple’s home often welcomes a flock of friends and family. A sprawling basement full of toys and games occupies the kids while the adults gather upstairs in a circa-1970s conversation pit, often to discuss matters of faith and the pressures and temptations of the modern world.

Linas and Rima have not only practiced their faith, they have been active advocates. Rima taught teen catechism classes for many years. Linas writes a column for a newspaper published by the Chicago-based Lithuanian Catholic Press Society.

Together they offer Pre-Cana classes for young couples and often speak to groups about the sacramental meaning of marriage. And they wrote Marriage — The Great Adventure: A Catholic Couple’s Guide to Lasting Love, marshaling insight from 45 years together about what makes a couple and a family thrive.

“It takes audacity for us to do that,” Rima says. “We have to be confident in our faith and what we’re talking about because we’re not promoting us, we’re promoting what we believe the Catholic Church has to offer as far as marriage goes.”

There’s a quality to the couple’s interaction that gives even a new acquaintance an impression of their marital connection, evident as they discuss the state of the institution.

“It was a little bit of a shock to us . . . ” Linas says.

“Way back . . . ” Rima inserts.

“. . . way back when, we found that basically everybody’s cohabitating and they don’t know the meaning of the sacrament anymore. If there’s love, anything . . . ”

“. . . anything goes.”

The back-and-forth goes on. Not finishing each other’s sentences so much as amplifying thoughts, two people of one mind, speaking with one voice.

Faith and works

When Floyd Kezele ’73 was a high school sophomore in Gallup, New Mexico, he spent two days in a sixth-grade classroom as part of a future teacher program.

“I told my parents I would never want to do that in my life,” Kezele says. And he never did.

For many years, Kezele held multiple jobs at once. He spent more than four decades as a criminal justice professor at the University of New Mexico-Gallup. He served as a judge for Native American communities and consulted from Alaska to Florida on tribal legal systems — a white man whose approach to crime and punishment resonated with Native traditions. He trained aspiring police officers in the state academy, including Erin Toadlena-Pablo, a Navajo who became Gallup’s first female police chief in May. He built homes. But teaching grade school? Never.

When the pandemic and a good buyout nudged him into a reluctant retirement from UNM a couple years ago, the local public school district contacted him about starting a high school career program in criminal justice. That sounded appealing, but the plan stalled. Instead, the district asked him to teach sixth-grade world history.

Decades after his vow, Kezele found himself last fall back in front of a bunch of sixth graders. “Didn’t remember what I told myself until afterward,” he says. That turned out for the best, because he relished the experience so much that he reupped for a second year.

Among the rejuvenating experiences of summer break, Kezele and his wife, Emily, spent time with their nine grandchildren — all together in one place, a milestone — and celebrated their 40th wedding anniversary on a 10,000-foot peak at Yellowstone National Park. They had another trip to Texas planned, but as always, life would lead him back to Gallup.

After graduating from Notre Dame and law school at Loyola University New Orleans, Kezele went home to practice. “I was a horrible lawyer from the standpoint of making money,” he says.

His consultation fee was $20.80. One day a couple came in to talk about a divorce. The meeting ran long, so Kezele’s secretary left him to close the office.

“What time did you leave?” she wondered the next day.

“About 3:30.”

“Had to be after 3:30, I left at 4.”

“3:30 in the morning,” Kezele said. “But I forgot to collect from them.”

Getting the $20.80 — over the protests of his secretary, who thought a 12-hour consultation merited somewhat more — took months of billing and a threatening letter. “But I’m not really threatening,” Kezele says.

Maybe he should have charged for marriage counseling rather than legal advice. After the meeting, the couple decided to reconcile.

“Ironically, that couple’s grandchildren went to Gallup Catholic School with my kids,” Kezele says. “I saw them in the basketball gym cheering on their events and stuff like that. So, God is good.”

He often repeats a variation on that refrain as he reminisces. In fact, the combination of divine guidance and insufficient funds has been a wellspring of grace on more than one occasion.

In 1983, with the first of his five children on the way, Kezele took a $9 per hour job as chief judge for the Pueblo of Acoma. On his first day in court, a defendant came before him with “a list of offenses as long as my arm.” Offered the chance to speak before sentencing, the man made no statement and the judge prepared to send him to jail.

As Kezele tells the story today, it sounds like a sitcom scene. Each time he said, “It’s going to be the order and judgment of this court . . .” his assistant would chime in with information the new judge might not have known yet. The cost to the court to house an offender in the jail ($24 a day). The amount in the court’s budget ($200).

“I couldn’t send the guy to jail for 10 days without kicking 40 bucks of my own in. And so, the good Lord, again, strikes,” Kezele says. “I said, ‘Young man, this is the first time you’ve appeared before me in court, right?’ This was the first time I was ever in court myself as the judge, so he said, ‘Well, yeah,’ probably thinking I’m crazy.”

That little loophole provided an opening to order the man to attend GED classes, alcohol counseling and community service in lieu of jail time. Kezele’s priority became avoiding prison sentences whenever possible — “I figured any monkey can do that” — instead offering alternatives that were more productive than punitive.

Those who failed to fulfill the judge’s mandates faced consequences. Miss a day of community service, and Kezele would add two days to the sentence. “That worked out,” he says. “There was one guy it didn’t work out, and he ended up working 176 days on a five-day sentence.”

When he started as a judge, Kezele had no training, but the approach he developed out of humane instinct and fiscal necessity aligned with widely held Native views of atonement rooted in admissions of guilt and sincere amends to individual victims and to the community at large. So grateful were the communities he served that a Comanche woman adopted him as “a son in the blood.”

“A lot of tremendous experiences,” he says. “And I thank God’s grace for showing me what to do.”

The Catholic diocese in Gallup has been the guiding light of his spiritual life. There have been struggles in recent years — the local Catholic high school closed and the elementary school had to be sold. A grade school with 90 students operates out of a parish hall, but geographic and economic realities limit enrollment. Covering 55,000 square miles in New Mexico and Arizona, the sprawling Diocese of Gallup is the largest by land in the continental United States and, Kezele says, “probably the first or second poorest.”

He’s raising money for a “Community of Saints” scholarship program to make the elementary school accessible to the children of Gallup’s predominantly Native American and Hispanic residents. “So that we have a prayer community behind the school and behind each student,” Kezele says, “and then a financial commitment to build a community of saints as well.”

Faith and need aligned again, a circumstance where the good works of a prayerful, community-spirited man have always flourished.

Jason Kelly is an associate editor of this magazine.