Standing there naked in the Rock with 25 other freshman boys in their birthday suits, I was puzzled and a little cold. Freshmen at the University of Notre Dame in 1971 were required to take a swim test. I didn’t understand why swimming was so integral to citizenship or studenthood or manhood or anything else, or why an institution with so much money couldn’t afford to give students swimsuits. Perhaps shedding ourselves of all our condiments was a way to level the playing field — while many students were upper class, many of us weren’t. I jumped in the water and completed the test without any hardship, and scurried to get back into my clothes. I first realized that Notre Dame was an all-male institution and wondered what I was getting into.

Two days before, I had also felt exposed and alone. My brother dropped me and my duffel bag off after a long trip from northern Wisconsin. I headed to Stepan Center to pick up my ID and class schedule. “You’re not on our list,” said the kindly old lady, running a scrawny finger down a printed page of names. “Sorry, there’s nothing I can do.”

Dazed, I wandered away with tears in my eyes and felt a warm hand on my shoulder.

“What’s the matter son?” said the old priest.

“They don’t have a record of me,” I mumbled.

I had received a rejection letter from Notre Dame, followed two weeks later by an acceptance and a Morrissey room assignment. The priest pulled up two old metal chairs and asked, “What kind of classes are you interested in?” We picked out my coursework and he got me an ID. To this day, I don’t know how the mix-up happened.

I started my Notre Dame adventure not knowing whether I belonged. I chose the school to get far enough away from home to reinvent myself in a place where nobody knew the old me — to find diversity, explore the world, discover who I was.

Had I taken too big a leap?

On the night before the first home football game, I heard steady drumming in the distance and raced out of Morrissey Hall to investigate. The pep band was marching the campus sidewalks, drawing students from their dorms for a rally. I found myself on a path with the band coming towards me. Gripped with excitement at the beauty and precision of the Irish Guard leading the way, I flattened myself against the barrier separating the walk from the lawn to allow the band to pass. A Guard picked me up and hurled me over it like I was a piece of dirt. It was impressive.

My first thought was from the Wizard of Oz: I’m not in Kansas anymore. Football seemed to be important at Notre Dame.

The university did what all good schools do — structure student life enough to provide healthy direction while looking away enough to allow students to learn from their choices. The structure provided a safety net, the freedom nurtured growth. I dove into my books, studied hard, hitchhiked to the Michigan border on Friday nights to drink at the 18-year-old bars, and said yes to whatever experiences presented themselves.

That fall I was studying in my room with the window open when I heard excited shouting in the distance. There was a vague sense of conquest in the air. A few boys started the trek to Saint Mary’s. Word spread like wildfire through the halls, numbers swelled and an organic, leaderless mob made its way to the dorms of Saint Mary’s. It was a panty raid.

We went from dorm to dorm, looking up, joking, singing, cajoling. The girls hung out their windows swinging their panties invitingly in the night air, then flung them down on the adoring crowd. From the girls’ perspective, it involved coy seduction from afar and just enough participation to retain female innocence and give a sense of male satisfaction. The women provided exactly the degree of intimacy the men deserved. It was a badge of honor to wear a panty on your head during the return trip to campus. The men released their libido in a relatively harmless way and the women had an excuse to upgrade their lingerie.

This medieval kingdom that was Notre Dame in 1971, with its turret-ringed halls and male hierarchy, needed a king, and we elected King Kersten as our student body president. His Lordship (or the Prime Mover as he preferred to be addressed) was a pre-med student who ran his campaign from a stall in a Walsh Hall bathroom. Wearing a long robe and crown, he strode out a window after dark onto the hall’s porch roof to address the rabble. With his vice president, a cat, perched on his shoulder and standing between two metal waste baskets ablaze, he made a few declarations, all forgettable; it was meant to be a spectacle to mock the politics of the day. We were fed up with the establishment, fed up with the Vietnam War, fed up with the civil rights situation in our country, and voted him in.

Long days were occupied with academics. We had everything we needed — pencil sharpeners in every classroom so we could take notes cleanly, slide rules to calculate, South Bend women to typewrite our handwritten term papers. The library had entire floors of quiet cubicles for studying. We lived on campus all four years and walked to classes. The professors were outstanding, teaching clearly and, for the most part, with heart.

We were mostly free of distractions. No cellphones, no personal computers, no internet, the rare room with a TV, the rarer student with a car. We listened to music on radios or record players and talked to each other. The women attending class on campus from Saint Mary’s were so few that it took an effort and therefore a choice to meet them. Competition was fierce, and often the effort seemed too much.

Winter turned to spring and songbirds returned to campus. One warm day we were packed in a chemistry lecture hall listening closely as Emil Hofman described chemical bonding on his overhead projector. The back door of the auditorium opened and two naked male streakers — dressed only in tennis shoes and ski masks — raced down the aisle and out the front door. The first streaker had “Hi” in marker on his butt, while the second had “Emil” on his cheeks. The class gasped in unison at the sight. Emil continued as if nothing had happened. I wondered what it was like to have been the calligrapher on that job.

What was normal here? Did I want to be normal? Did I want to be extraordinary? Could I even afford to be normal? We all wanted to be free and wild . . .

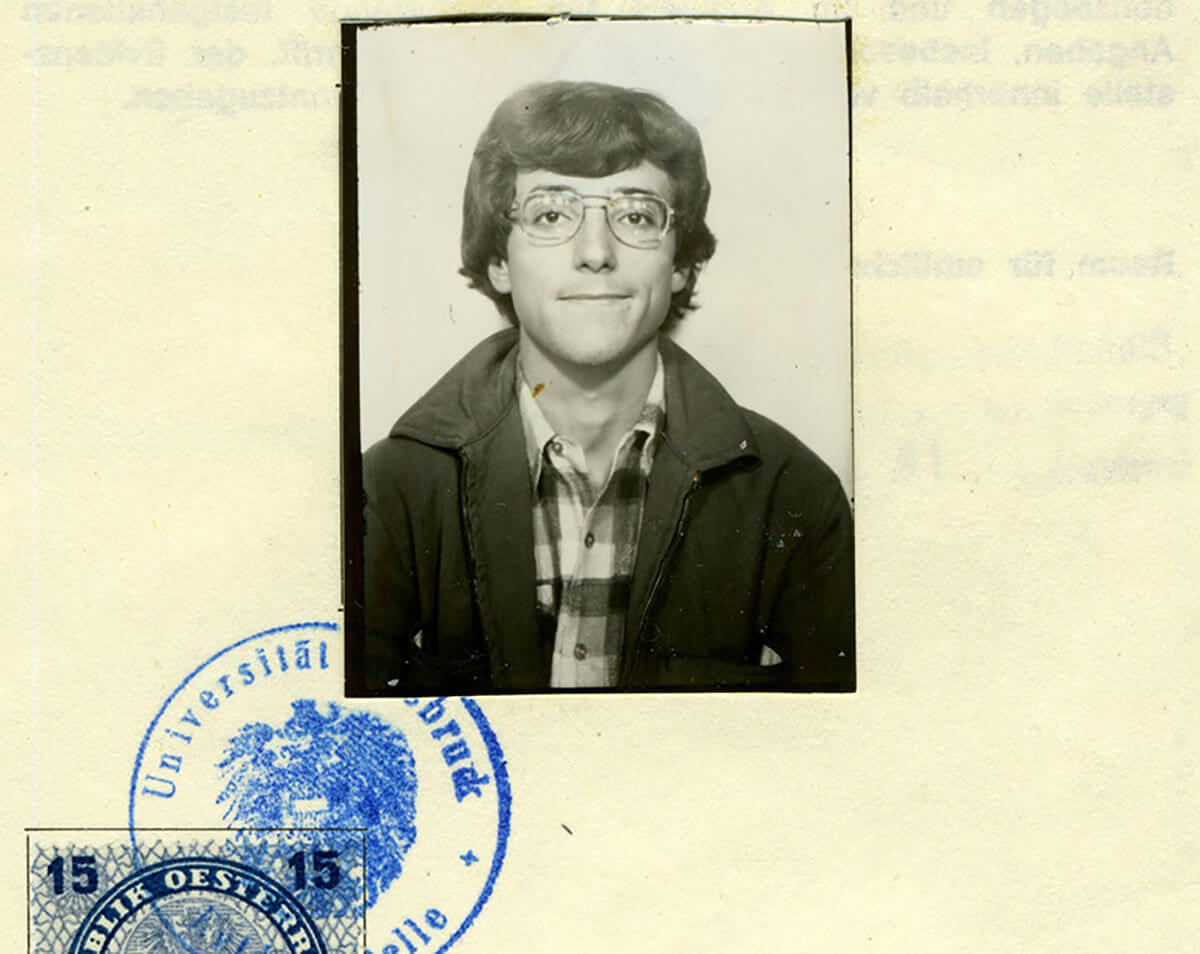

The next year I studied in Innsbruck, Austria. I grew up in a lot of ways. I went from being paralyzed to speak a foreign language to a more relaxed “I don’t give a damn that I’m not perfect, but I’m trying.” I learned to ski on mountain slopes which four years earlier had hosted Olympic slalom races, and hitchhiked to Ireland. I lived with elderly survivors of World War II, so frugal that they allowed two inches of water weekly for bathing (the Herr was agreeable to twice-weekly one-inch baths) and a chunk of coal to heat my bedroom in the winter, which was cut in half when my roommate was away (the Herr saying that I only needed to heat my half of the room).

I had peaks and valleys over there, gazing down one week in awe on breathless views of rugged, snow-capped alpine summits — stretching from Germany in one direction to Italy in the other — and the next week staring blankly from a bridge at the water below after learning by letter that a dear friend had died back home.

My world was expanding so quickly with each new experience that I didn’t have time to take stock or to judge. I felt like a leaf on the ocean, cresting from wave to wave, neither expecting nor surprised by what was on the other side.

We attended the Munich Summer Olympics. In a natural bowl on the perimeter of the Olympic grounds, a group of young people danced completely naked, whirling, singing and laughing. Two days later a group of Palestinians kidnapped and murdered the Israeli athletes at the games. The fruits of freedom and the lack of freedom were expressed that week.

My world was growing.

Early Friday mornings were spent helping handicapped kids in a swimming pool. At the first session I found the two locker rooms marked Herren and Damen, went into the men’s room, sat on a bench, and took off my shirt. Two girls my age came in and sat down on either side of me. We all started chatting, but I wondered if I was in the wrong place. The girl on the right took off her shirt and bra, and when the girl on the left did the same, I continued to undress. We carried on talking without skipping a beat, putting on our swimsuits. The Austrians view the human body differently than we Midwesterners. I wasn’t in Kansas anymore.

Returning to Notre Dame, the same questions were there: What was normal? Where did I belong? What did I want to become?

The academics were insane, fitting in a science degree with the Innsbruck year. The football team won a national championship. Coach Ara Parseghian was idolized (“Ara stop the rain”) and Rudy finally got his chance to get on the field.

Days of study melted into weeks. Late nights were spent underground identifying minerals in the “dungeon” of the geology building or punching holes in cards and feeding them into the mainframe computer in the engineering building. It seemed the world was moving on without me. I was pumping myself with facts while my friends back home were starting families.

Notre Dame had gone coed while I was away. Women were welcomed to be sure, but with the unspoken caveat that they were being asked to integrate into the Notre Dame lifestyle — the school wasn’t yet at the point to reimagine itself. The men considered the few women on campus exotic. Men expressed their appreciation for this new grace in their lives by “passing them up” at football games and placing nipple-colored waste baskets on top of the ACC domes. Why is diversity feared? Why can’t we integrate into each other’s lives? Why can’t we all just be equal?

Our lives revolved around study and football. When the season was over, the South Bend winter seemed gray, cold and long.

Senior year arrived. I ran around St. Joseph Lake every morning at sunrise, ending with a swim into the center of the lake. Rolling over onto my back and feeling the low sun slowly whisking away the steam rising from the water, it seemed that life was unfolding as it was meant to be. The beautiful routine ended the third week of November as I lay in the lake, snowflakes gently building up on my eyelashes. Something magical was coming to an end.

Winter came and went and the last semester started. The professors had an unwritten understanding that second-semester seniors would not be tested at the end of the term; our part of the bargain was to attend all classes and participate in daily assignments. We enjoyed weekends at the Indiana Dunes, free of the stress of studying for finals.

Suddenly, without warning, I was entering a crossroads. The end was near and I had no interest in working in the oil fields of northern Alaska or Iran. The farthest thing from my mind when entering Notre Dame was to get an education to become employable. My girlfriend had two more years to go at the University, and our warmth and companionship were important to us. I signed up for four more years with Our Lady, this time in engineering and law.

As the song goes, “I know what I was feelin’, but what was I thinkin’?”

The excitement of something new wore off quickly under the burden of graduate school. It was four years of pushing a boulder down the road. A boulder so big that I couldn’t see the other side. No magic, no exploration, only a view of a massive gray object in front of me. So heavy that I needed to keep it moving — losing momentum would make it impossible to start again. No serious thought to quitting and cutting losses. The football team won another championship. I drank beer at midnight to fall asleep. I grew four years older. Was I out of my league? Was I out of my mind? What was I thinking?

A glimmer of hope appeared my last year under the Dome, when I directed the law school’s Legal Aid and Defender Association. I worked on migrant farmworker issues and finally felt a sense of belonging. Those families were on to something. In spite of their poverty, they were rich in relationships. One evening I visited an extended family in an orchard, sitting in the tall grass in a semicircle around their grandfather. He sat on an old couch in the shade of an apple tree, a beloved patriarch silhouetted by the setting sun, regaling his loved ones with stories about where they came from and who they were. The image remains etched in my mind.

When I returned to the car, a tire had been punctured by the farmer.

Spring of the final year arrived and life beckoned. Sitting on the steps of the law school late one evening, humming to myself the refrain of the Neil Young song “A Man Needs a Maid,” I looked up at the lighted clock faces on the cathedral peering down at me like the eyes of a Tolkien figure. The warm night air called me away from the stuffy law books. I walked aimlessly across the empty main quad and saw a light on in the corner office on the third floor of the administration building. Father Hesburgh was in.

I went into the building, found Father Ted’s office and walked in. He looked up from his papers at the disheveled, long-haired student before him. I told him I wanted to serve the poor when I graduated, he listened quietly and suggested I read a book he had recently published, The Humane Imperative. Walking down the stairs after our meeting, I felt like Moses returning from the mountain, still confused yet hopeful.

Father Ted was a treasure. He fought for civil and economic rights on the national and world stages. He was a pragmatist and a beacon for steady movement toward Christ’s message of inclusion in a tumultuous time where violence sometimes diluted the message. In my roller coaster experience at Notre Dame, Father Ted was a constant. Without any conscious sense on my part of his presence in my life, the man had quietly cut a furrow which I was about to follow. A good leader does that.

I skipped graduation ceremonies and pointed my car south towards the hills of Appalachia rather than home to Wisconsin. Driving down Notre Dame Avenue past the cemetery for the last time, I saw the Golden Dome in the rearview mirror.

I felt satisfied and happy.

Today, half a century later, retired from a successful career in hydrogeology, I reflect on that time of my life. I learned important lessons in the classrooms and halls of Notre Dame, on the high footpaths around Innsbruck, and in the orchards of southwestern Michigan. I learned to get off the bench and get into the game. Explore the edges of your comfort zone with an open mind. Seek diversity and relationships. Help those in need.

Your essence flows from these pursuits.

Maybe being out of your league is the only way to fully live.

Don Brittnacher and his wife, Chris, have three daughters, Heidi, Anna, and Mollie. Mollie died of cancer at age 7, and Heidi and Anna honor her by running a charity called Mollie’s Angels and working as a child life specialist.