Rustin in 1965

Rustin in 1965

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.” —Bayard Rustin

Civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, who was a member of the Notre Dame board of trustees, is being introduced to a new generation. Often relegated to the background during key civil rights events of the 20th century, Rustin’s long career as an activist and “troublemaker” is being recalled and celebrated.

A new biopic, Rustin, released in November on Netflix, recounts how Rustin, facing racism and homophobia as a Black gay man, joined the civil rights movement and took a lead role in planning the historic 1963 March on Washington.

At the August 1963 March on Washington, which drew hundreds of thousands to the nation’s capital, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., standing in front of the Lincoln Memorial, delivered his landmark “I Have a Dream” speech. Rustin can be seen standing behind and to King’s right in photos of the speech.

Born 1912 in West Chester, Pennsylvania, and raised by his maternal grandparents, Rustin attended Wilberforce University, Cheney State Teachers College and City College of New York. He devoted his adult life to working for civil and human rights.

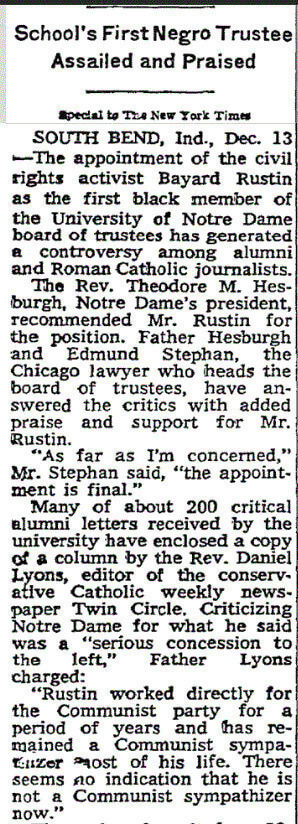

Rustin became a Notre Dame trustee in 1969, two years after the University shifted to a board composed primarily of laypeople. He was recommended for the board by Notre Dame President Rev. Theodore M. Hesburgh, CSC, who had been serving on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission since 1957. At the time, Rustin was executive director of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an organization for African American trade unionists.

When Rustin joined the board, Notre Dame administrators received letters from some alumni and conservative Catholics outraged at the appointment. The letter writers cited Rustin’s involvement as a young adult in communist causes and his 28-month prison term during World War II for — as a lifelong Quaker pacifist — refusing to serve in the military.

The University didn’t back down. “As far as I’m concerned, the appointment is final,” said Chicago attorney Edmund Stephan ’33, chairman of the board of trustees at the time. Rustin served as a trustee for about five years.

Rustin drew headlines only once during his time on the board. It was May 1, 1970 — just as the Nixon administration was expanding the Vietnam War into Cambodia, seeking to eliminate support there for operations against South Vietnam. (This was three days before the shootings at Kent State University in which four unarmed students were killed and nine others wounded by the Ohio National Guard during an anti-war protest. Those events led to a seven-day strike by Notre Dame students.)

On May 1, student protesters attempted to disrupt a board of trustees meeting in the Center for Continuing Education on campus. About 200 students managed to slip inside the locked building, and some began pounding on the door of the room in which the trustees were gathered. They demanded a meeting with the full board.

Rustin and a fellow trustee, Thomas P. Carney ’37, agreed to meet with some of the students in the building’s auditorium. An informal discussion followed, with four Black students demanding the University provide more scholarship funds for African Americans, the South Bend Tribune reported the next day.

“We’re not here to fool you,” Rustin told the students. “We have no ability to negotiate with you today. We came here to find out what you want. We would be playing games if we told you we could make decisions without approval by the entire board.”

“I am black and on the board. Send me facts and I will help you. There is no need to yell dirty names around here,” Rustin admonished the youths. “I’m going to the board meeting clothed with facts. I’m not going to get it by screaming Black Power.”

The two trustees were repeatedly interrupted and shouted down by some of the students, The Observer reported. The student protesters called for recruitment of more minority students, resolution of grievances over student financial aid and demands for coeducation. The protestors made so much noise that the board of trustees cut its meeting short.

Rustin’s civil rights philosophy differed from some of his contemporaries. He was opposed to the notion of reparations to Blacks to atone for the sins of slavery, considered many “Black studies” offerings non-scholastic and disagreed with Nation of Islam leader Malcolm X’s backing of racial separation.

Rustin’s commitment dated back decades. In 1941, he was the first field secretary of the Congress of Racial Equality. In 1943, during World War II, Rustin was imprisoned as a conscientious objector for refusing military service. In 1947 he participated in the first of the “freedom rides” to defy segregation laws in the South, resulting in a 22-day sentence on a Black chain gang. His report of that experience prompted an investigation which led to the abolition of chain gangs in North Carolina.

Rustin didn’t hide his sexuality. In 1953, he was convicted on a “morals charge” in Pasadena, California, for having consensual sex with men. He was forced to cancel upcoming speeches and resign from his position with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a pacifist organization. “I know now that for me sex must be sublimated if I am to live with myself and in this world longer,” Rustin wrote to a friend while serving his 60-day sentence in the Los Angeles County Jail. In 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsome posthumously pardoned Rustin.

In 1956, Rustin traveled to Alabama to support the Rev. Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Bus Boycott. He helped King organize the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He served for seven years as an assistant and mentor to King, introducing him to Mahatma Gandhi’s approach to nonviolent civil disobedience.

Shortly before the March on Washington, Sen. Strom Thurman verbally attacked Rustin on the Senate floor, recalling his conviction of a decade earlier and referring to it as “sex perversion.”

In 2013, Rustin was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Barack Obama. (The new film about Rustin is produced by Higher Ground, the production company of Barack and Michelle Obama.)

Later in life, Rustin became much more public about his homosexuality and worked to bring the AIDS crisis to the attention of the NAACP. “I think the gay community has a moral obligation . . . to do whatever is possible to encourage more and more gays to come out of the closet,” he said in a 1987 interview with The Village Voice.

For the last decade of his life, Rustin was in a committed relationship with a partner, Walter Naegle, who was decades his junior. The two formalized their relationship in the only way that was possible for gay people in the time before gay marriage was legalized — Rustin adopted Naegle as his son.

Bayard Rustin died on August 24, 1987, at age 75.

Margaret Fosmoe is an associate editor of this magazine.