Regis Philbin in his element, on campus and in front of a camera, in 2004. Photo by Matt Cashore ’94

Regis Philbin in his element, on campus and in front of a camera, in 2004. Photo by Matt Cashore ’94

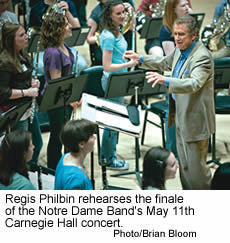

Editor’s Note: Regis Philbin ’53, the legendary TV personality and devoted alumnus who broadcast his love for Notre Dame from coast to coast, died Friday night at age 88. We remember Philbin with a look back at this 2010 profile that charts his career.

It’s 2007 and I’m trying to catch a plane from Miami to Newark on Super Bowl Sunday, hoping to get home in time to see whether the Colts would handle their business or the Bears would hoist their second championship. As I boarded I saw, nestled there in first class among those flying for business or wanting just a little extra comfort, Regis Philbin.

I had heard frantic whispers as I got near the entrance, and now it became clear what it was about. Philbin, Notre Dame class of 1953, seemed relaxed and, if they were talking about him, somewhat unaware. This could be a down-to-earth peaceful style, it could be surliness, I had no idea. Shrugging, I took my seat and prayed to the airline gods that this clock-watching football fan didn’t miss the biggest game of the year.

When we landed, Philbin was too far ahead for me to know how he deplaned. Did everyone give him room, did he give dirty looks, couldn’t tell you. Honestly, I wasn’t even thinking about the guy. Again, the game. Get home, get food, get game. As I waited for my ride, I did happen on the talk show host yet again, and there, sure enough, was his abundant entourage, all making sure to crowd around him.

Another guy filled with self-importance. Of course.

But as I got a closer look, I realized they were strangers, every one. These weren’t bodyguards, but fans, hoards of them, begging for a picture, an autograph, just a moment for him to listen to how much they loved him, no matter how you’d define that love. One man of a linebacker build crumpled Philbin with a muscled arm, which swung around deftly as the camera flashed, momentarily disorienting the star. I searched his twitching eyes for boredom, for that darting motion of someone seeking any kind of refuge. Didn’t find it.

Regis Philbin had made some new friends. And that, for him, clearly made for a good day. As the mob slowly dispersed, shouts down to murmurs, he was left with his cart. Taking a breath, Philbin, with a confident gait, pushed on, just a man looking for his ride at Newark.

Bronx boy

It actually began for Philbin not so far from where I saw him in Newark. Growing up in the Depression-era Bronx during the 1930s, he understood what going without could mean and so, too, did his parents. Still, he wasn’t about to trade in his dreams for just any practical employment.

When Philbin let his mother and father in on his plan to become an entertainer, he says, “My mother was crying. My father was furious.” They had sacrificed for his schooling, and now he wanted to do something that, in their opinion, any person could do. No, any bum could do. Philbin had gotten his first real taste of rejection.

Not even close to his last.

Philbin knew he had to start from the bottom to become an entertainer, but he did choose a slightly more realistic approach, trading in the idea of being a singer for aspirations of television, a relatively new business with many more chances for advancement. Starting off as a page at NBC, he would become a stagehand at KCOP in Los Angeles. “I would write reviews of the station programs and thumbtack them on the wall,” he says.

Philbin had the right medium but still wasn’t heading in the direction he wanted. Remember, he fell for the entertainers on TV, not the reviewers. “The first big show I ever saw was The Milton Berle Show — the Texaco Hour,” he says. “And he was the beginning of the whole thing in terms of entertainment. The years would go by and there was Martin and Lewis on The Colgate Comedy Hour.”

From dusk to dawn

After years of stints at everything from driving film around in a truck to writing sports copy, Philbin finally found a star who would give him a chance. That first big break came in 1967 when Rat Pack favorite Joey Bishop got an eponymous late night national show and chose the eager Bronx native as his sidekick. Philbin knew the deal — make Bishop look good then stand aside.

“You understand who’s paying you,” he says, adding, “If I got a laugh, fine, but I didn’t want to get too many of them.” Philbin referred to their 1969 cancellation as a “crushing defeat” of a “losing show,” but relatively speaking, it was the opposite. Anything lasting more than a season is considered a rousing victory, but as Philbin has been at his present production for more than 25 years, it’s fair to see where his analysis comes from.

Hard work, much of it thankless, would follow. But it’s what’s usually required when waiting in line for the big time, and Philbin would be the first to tell you how difficult it can be on your personal life.

“If you’ve been out of a job for some time you realize you do whatever you have to,” he says. “I [ultimately] had an opportunity to do what I wanted to do with a morning talk show. . . . I also enjoyed being a news reporter in San Diego and became important to the station. It was tough on my family, coming back after the 6 o’clock news and then maybe having to hit another assignment. We all understood I would have to do it, but it takes a great toll when you sometimes have to go on the air three times a day.”

He’d continue to take almost any hosting gig he could get, finally catching his rhythm with New York City’s WABC in 1983 with The Morning Show, which would ultimately develop into Philbin’s present program. It couldn’t have worked any other way, says Philbin, but in the instant format.

“The live factor means everything to me,” he says. “A different momentum. . . . When I was on a taped show they worried about if the flowers were perfect. Here, it’s ready or not, here we come.” Though the show began two years prior, it was the teaming with Kathie Lee Gifford in 1985 that helped it become a sensation, leading to the 1988 syndication of the newly titled Live with Regis and Kathie Lee.

This higher level of fame saw Philbin on the talk show circuit now as a guest, maybe no better fit for him than David Letterman. “I remember how funny it was that he was unbelievable as a host but uncomfortable when he was the one being asked the questions,” says Peter Lassally, a former producer of Letterman’s show. “This went on for a bit on Letterman. Then he finally got the idea to tease Dave about why they can’t be friends and have dinner together. Dave would reject him. Why can’t we play tennis? Dave again would reject him. Regis became one of the best guests on TV from that small idea.”

He got game

For most, the zenith of success comes, at latest, at middle age. Philbin thought this was also the case for him, maybe a little short of his dreams but a good life. He was parodied on Saturday Night Live (Are ya ready for this?! Are ya ready for this?!), had a national following and was beloved by those who had time to watch Live as part of their hectic morning.

It really didn’t seem it could go anywhere but down. Still, Philbin, who clawed for everything he got, decided to get out those tough New Yorker talons one more time.

When producers were considering who would be the host of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire, based on the original British version, Philbin assures me he wasn’t on the short list — or even the long. “With the three lifelines, the big pot of cash waiting for them and 15 questions,” he says, “I thought it was a very unique show.” Regardless of whether he leapfrogged everyone through his persistent lobbying or was the beneficiary of someone secretly turning down the gig, Philbin’s career would be forever changed with the show’s debut on August 16, 1999.

The dramatic pauses, the easy questions leading to the impossible ones, all meshed with his rooting style. When Philbin would ask if the contestant was feeling up to the next question or when he’d soothe their nerves, he made us believe he meant it. He was on their team and invited all of us to climb on the bandwagon. Finally, when John Carpenter took the top prize by using his lifeline to call his father — not to ask his opinion on the question but just to tell him he was about to win it all — Philbin reached a milestone. Not far from 70, he had simply become a part of one of the great moments in television.

And so scenes like the one at Newark Airport became commonplace. No matter where he went, people wanted a moment with the man who made “Is that your final answer?” the most popular question in America.

“In a situation like that at an airport, there’s no escape, and I don’t want to escape,” he says. “I know it aggravates people in our business. After a while you want to run away and hide — I know how they feel. But I’ve enjoyed the screen and stage and maybe it could bring a thrill to somebody. So maybe you make it work for you . . . shake hands and smile.”

Walking away

At 78, Philbin, admittedly, is not in the same shape he was a few years ago when he glided that airport cart through an awaiting crowd. He only recently has returned to the now-titled Live with Regis and Kelly — Kelly Ripa swapped in for Gifford in 2001—after weeks away to get a hip replaced. For the first time, it makes this celebrated man of unlimited energy seem older.

He knows it. He doesn’t deny it.

“I had a triple bypass four years yesterday,” he starts, like he can’t even believe what he’s about to say. “You have a hip replacement. I’m at the point now where I’ve had a good life and I think television is great, but maybe it’s time to wrap it up.” That would be the toughest decision of all for someone who waited seemingly forever for success, who fought for that deeper recognition which eluded him until the age when many are already retired.

Philbin assesses one more time, with a statement he never would have uttered even 10 years ago. “I think I’ve accomplished everything,” he says, in a softer, more resolute tone. You wait for a quick joke to undo the thought but it’s not going to come.

The man who entered the record books in 2004 as the most filmed personality ever goes quiet soon after the remark, so quiet, letting this once-foreign idea of contentment hang. No applause, no one-liner, no need.

Do you believe it? Silence is suiting Regis Philbin just fine.

Eric Butterman previously profiled producer John Walker and technical director Casey Dame for this magazine. Reach him at ericbutterman@yahoo.com.