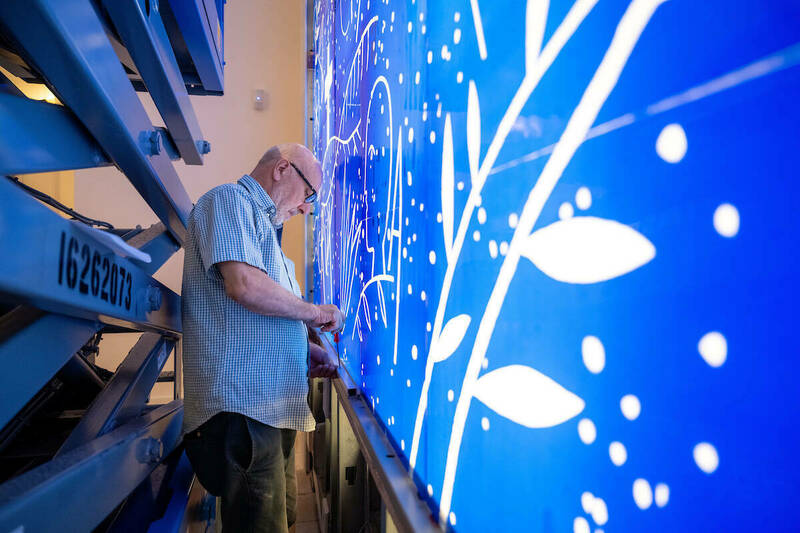

Lino Reduzzi, a longtime collaborator with fellow Italian artist Mimmo Paladino, installs stained glass in the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art chapel. Photo by Barbara Johnston

Lino Reduzzi, a longtime collaborator with fellow Italian artist Mimmo Paladino, installs stained glass in the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art chapel. Photo by Barbara Johnston

Editor’s Note: This is part of a Notre Dame Magazine series documenting the move from the Snite Museum to the new Raclin Murphy Museum.

- Snite Moves

- Packed Schedule

- Moving Works of Art

- Museum Pieces

- Divine Inspiration

- Raclin Murphy Readies for Its Debut

The Vatican Museums house the Sistine Chapel, officially the final stop on that bucket-list tour. When the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art opens on campus later this fall, the famous chapel’s Notre Dame counterpart will be named for Mary, Queen of Families, and you may want to make it your first.

Designing a university art museum with a chapel may be an unusual move. But Joseph A. Becherer, the Raclin Murphy’s director and sculpture curator, says this brainchild — one remarkable facet of the larger effort to create a suitably grand and up-to-date showcase for the University’s extensive art collections — is just “so perfect” for Notre Dame. It comes from the heart, and it will make the Raclin Murphy “distinct among museums, period.”

Becherer believes the chapel, located above the front entrance on the museum’s second level, will offer visitors the ideal context for understanding the religious works in the University’s estimable collections, particularly those in the Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque galleries immediately to the chapel’s left and right.

“Lots of museums are going to have a very healthy number of these kinds of religious works,” he says. “However, in the context of a museum . . . they have lost their first life,” meaning they were made for home chapels and churches as aides for prayer and worship, and not merely as beautiful objects for art galleries.

But if the presence of an actively used chapel can “animate” the art in the galleries around it, he says, the opposite is also true. Inside Mary, Queen of Families, three venerable works of art frame the sanctuary. Two appear in niches on either side of the altar and the third between the altar and a wall of luminous, blue stained glass, forming a kind of triptych.

To the right is a 13th-century icon of the Madonna of Tenderness, “representing the Byzantine tradition,” Becherer says; to the left another Madonna, attributed to Gualtieri di Giovanni da Pisa in the early 15th century, whose blond child holds the playful detail of a pomegranate; and finally, “Holy Family with Saint Elizabeth and the Infant Baptist,” an altarpiece painted by Fra Paolino da Pistoia, a Dominican friar, in the 16th century, chosen to honor all artists among the professed religious.

Two alcoves at the back of the sanctuary will feature a rotation of glass-encased objects selected from rest of the Raclin Murphy collection. First up, a pair of chalices, one ancient, one contemporary. “We’re really hoping to underscore the significance of tradition and the innovation of past and present,” the director explains.

But that blue stained glass is a work of art in its own right, as are the incised paintings in the chapel’s thick plaster walls and the brilliantly multicolored mosaic inlaid in the concave oval ceiling. All are the creations of Mimmo Paladino, a prominent Italian artist of wide-ranging interests and talents whose religious work, Becherer says, includes the decorative programs of several churches and chapels, illustration of a new Italian translation of the Roman Missal and a large crucifix for the entrance of the Vatican Museums.

Best known as a leader of the Transavantgarde movement that began in Italy in the 1970s and ’80s and swiftly rekindled interest across Western Europe in symbol, representation and emotion in art, Paladino’s work expresses his great sensitivity and knowledge of the past, says Becherer.

Commissioning him to decorate the chapel inside a museum designed by a team from the firm of Robert A.M. Stern led by Melissa DelVecchio ’89 — a work of art inside a work of art — fulfills a wish expressed “very clearly” by students and faculty when Becherer arrived in 2018 to lead the creation of a new campus art museum. “More engagement with contemporary art” was the message, “and so we’re greatly increasing the amount of square footage for contemporary art in the museum in general,” he notes.

Toward this end, Paladino was an especially inspired choice — Becherer’s first, in fact — and the Benevento native reciprocated the excitement, devouring every detail Becherer could send him via coffee table books filled with Post-it notes about Notre Dame, the basilica, campus chapels, native plants, the Great Lakes watershed, the region’s indigenous history, the Congregation of Holy Cross, even the weird concept that is the American residential university. Everything.

“He was very fascinated with Touchdown Jesus,” Becherer recalls, “which is essentially a mosaic. Things like that.”

Tens of thousands of pieces of marble and colored (and gold-leafed) glass make up Paladino’s ceiling mosaic, a joyous, swirling universe of symbols responding to all that Paladino had taken in. References abound to Mary, to knowledge and church history, to the St. Joseph River and the baptismal role of water. Images of blankets evoke the enduring presence of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, while branches and leaves of Midwestern flora draw in the outdoor Charles Hayes Sculpture Park next door to the Raclin Murphy.

The overhead focal point is an image of the Holy Family. In it, the Christ child holds a tiny pomegranate: a symbol of abundant fertility, and now an immortal link with the Gualtieri Madonna painted in oils on canvas below it.

Artisans in Paladino’s studios in Italy realized his designs in a gigantic basin, an exact inverted replica of the museum chapel’s ceiling. They could only complete half the mosaic at one time because of space limitations, then cut the finished work into some 250 irregularly shaped panels for transportation to the United States. The entire process took more than 10 months, says Stefano Reduzzi, whose father, Lino Reduzzi, director of his own studio and a frequent collaborator with Paladino, led the installation of the work on site at Notre Dame.

While work on the mosaic proceeded, workmen applied Paladino’s designs for the “frescoes,” or incised paintings, at precise locations around the chapel’s rounded plaster walls, cutting through the drawings into the white surface to reveal a layer of gray plaster beneath. They gently underscore the themes that unite the mosaic and the stained glass, prominently featuring stars, the natural world, images of sustenance and illumination and two unmistakable references to the religious founders and enduring spirituality of Notre Dame: the crossed anchors and motto — Ave crux, spes unica, or “Hail the cross, our only hope” — of the Congregation.

Completing the chapel’s artistic unity, Paladino designed altar linens and vestments, one for each of the four colors — purple, red, green and white — of the liturgical seasons.

Becherer feels it is very important to link the museum’s rising engagement with contemporary artists with the Church’s traditional role as patron.

“One of the things I hope this museum does is shed a very bright light on the fact that, basically since they put loaves and fishes on the walls of the catacombs, the Catholic Church has played an extremely significant role as one of the greatest art patrons that has ever existed,” he says. “Maybe the greatest, but I’m not going to wrestle with an Egyptologist on that one.”

Weeks after the museum installation, Reduzzi and son returned with the three enormous panels of blue glass that catch the visitor’s eye from the other side of the museum. Made by hand at Glashütte Lamberts in Germany, the glass varies in shade like deep, clear water in sunshine. Lino Reduzzi thinly etched Paladino’s designs into its surface, then attached a white glass laminate to its backside before mounting it on the chapel wall. LED lighting behind the panels gives the illusion of a translucent screen protecting the chapel from the glare of daylight.

The chapel will hold permanent seating for 26 congregants with room for situational expansions. Becherer says the Mass schedule has not been set but expects the sacrament to be celebrated regularly inside Mary, Queen of Families. The name reflects a personal devotion of the late Virginia Marten, a Notre Dame benefactor and mother of 12 from Indianapolis.

“Not that we’re becoming a religious art museum,” Becherer hastens to say, pointing to the nearly two dozen galleries above, below and around the chapel that feature the noted collections of Mesoamerican, Native American, modern and contemporary art, photography and other growing highlights of Notre Dame’s quietly impressive history of art appreciation. “But it’s a very important part of our story, and it’s a part of the fabric of why we’re actually here.”

John Nagy is managing editor of this magazine.