Sometime last year, I determined, somewhat impulsively, that I had no choice but to move to Idaho.

As a budding journalist, the Wild West seemed a far more exciting playground than my Boston home. I would have great adventures involving ranchers and horses and tumbleweeds, probably, while covering one of the most interesting statehouses around. And so I accepted a job offer, packed up my car and headed west to Twin Falls, a small city that overfloweth with scenic views, Pizza Huts and nearly enough friendly characters to fill them all.

But this is not a meditation on the politics of rural America, nor a self-righteous screed on the importance of journalism, nor a humorous montage of yours truly chasing cows through a potato field. It is, I regret to inform you, something far worse. This is the story of how I adopted a hamster.

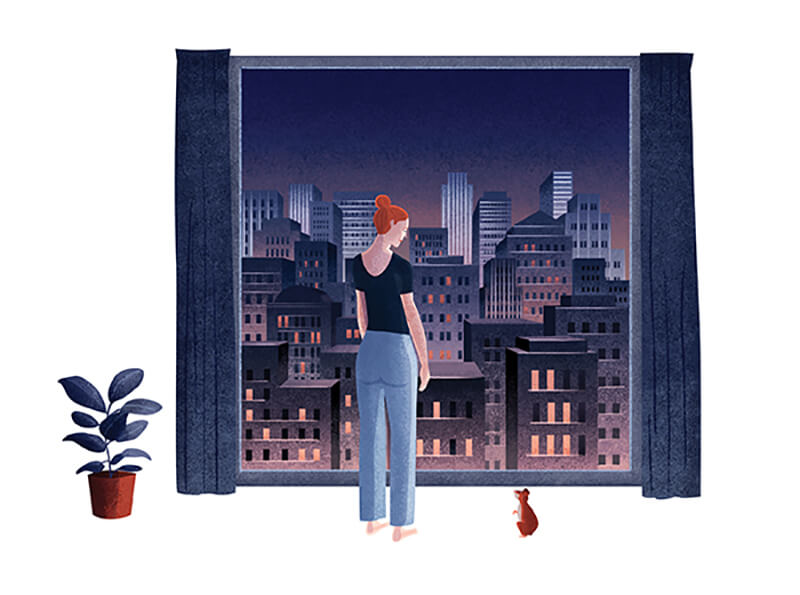

Illustrations by Bett Norris

Illustrations by Bett Norris

“A hamster?” you may say, glancing warily downward to the end of this essay.

“A hamster?” my parents will surely bellow, glaring with disdain at the cat who somehow found its way into my South Bend apartment and has since become a permanent resident of their home.

To you and to them, I say, unapologetically: Yes.

You see, after the excitement of moving cross country faded, when the novelty of living across the street from Chick-fil-A and down the road from real cowboys wore off, I arrived at a startling realization. For the first time in my life I was entirely alone. And in a small town with few young transplants, the possibility of friendship felt elusive at best.

“Why don’t you go to the library?” my mother suggested. “There are nice young people at the library.”

A visit to the Twin Falls Public Library’s monthly film club yielded a dispirited discussion of Jason and the Argonauts and enough individually wrapped hard candies to feed a family of Argonauts for a year, but, alas, no nice young people.

And so I sat in my furniture-less apartment, night after night, gazing out at the glow of the Popeyes next door and helplessly waiting for friends to appear.

“I think I might be pathetic,” I confessed to my mother over the phone one day.

“Oh, honey,” she sighed. “I don’t think it’s pathetic that you don’t have friends. But I do think it’s pathetic that you haven’t tried.”

She was right, just as she always was: when she warned me not to cut my own hair in the bathroom; when she predicted that my unrequited middle-school crush would go prematurely bald.

Enough was enough, I decided. No more tearful nights spent in bed with fast-food meals best described as soggy. Something had to change, and, as if delivered to Jason by the gods on Mount Olympus, the answer to my problems was suddenly, clearly laid out before me: I needed a rodent in my life.

A small, cuddly creature to come home to at night would certainly improve my situation, I was sure. Better curb appeal than a fish; shorter lifespan than a dog. And so I found myself at Petco, ready to rescue one lucky animal from the grubby grasp of an overenthusiastic six-year-old.

“Do you have any problem hamsters in the back?” I asked the teenage employee, pleased with my own altruism.

She stared at me blankly.

“No,” she said.

“Oh.” I turned to the nearest cage, where a large brown rodent was frantically going nowhere on a spinning disc. It was moving, and obviously alive, which was more than one could say for its listless, dim-eyed brethren, slumped in corners and staring suspiciously at us outsiders like tiny, drunken patrons of the Old West’s cutest saloon. “Can I hold that one?”

“No,” she said.

“Alrighty,” I said. “I’ll take it!”

As we exited Petco, hamster clawing at its box à la Madeline Usher, I knew I’d made a mistake. This creature had no interest in loving me. It was neither civilized nor pleasant; it had terrible manners.

The situation only deteriorated when I assembled its cage on the kitchen table and plopped it inside. It rose up on its hind legs, tiny front feet poised in ominous, mid-air anticipation, and its empty black eyes connected with mine. For a moment, time stood still. Then all hell broke loose.

My rodent flung herself at the bars of her cage, gnawing furiously. She grappled her way to the top of her turtle-patterned water bottle; she swung from the ceiling like a madwoman. “Stop!” I implored her, but she would not.

For weeks, we carried on this way. Gone were the dreams of traipsing barefoot through my sun-soaked apartment, furry companion on my shoulder and effortlessly baked quiche in hand. They had been replaced with nightmares in which I murdered my new nemesis and felt no remorse at all. What had I done to deserve its contempt? Why would it not just love me already, as God surely intended?

Gradually, the storm subsided. One evening I glanced up from a book to find my archenemy standing at the edge of her cage, eerily human-like hands grasping the bars, watching me exist. I moved; she flinched; and it occurred to me that perhaps I’d imagined the hostility in her eyes. Maybe, just maybe, my rodent feared me as I feared her.

“Hey,” I said. Her black eyes stared unblinkingly. With a fresh surge of courage, I reached for the cage latch and stuck my hand inside. Eyeing it cautiously, the creature inched slowly closer, sniffer twitching wildly. And then —

“Ouch!” I cried out, feeling wronged. The perp retreated into her plastic igloo, burying herself in wood chips.

- 6th Annual Young Alumni Essay Contest

- 1st Place: “Mendelssohn on the beach," Edward Jacobson '13

- 2nd Place: “Rodent," Gretel Kauffman '16

- 2nd Place: “I just happened to be there," Rachel Plassmeyer Bené '10

- HM: "Playspace," Laura Andrews '10

- HM: "Wherever we are," Jacqueline Cassidy '15, '16MSM

- HM: "A love letter to the internet," Johanna Kirsch Wilson '10

- HM: "Summer magic," Victoria McQuarrie '12

- HM: "Father-daughter time," Stephanie Nguyen '09

The moment was gone. But I’d tasted companionship in the fleeting seconds before my hamster tasted me, and I was determined to find that feeling again. And so we repeated this routine nightly, with what felt like a mutual understanding that these motions, while not particularly enjoyable for either party, were somehow necessary. Sometimes she bit; sometimes she hid; sometimes she brushed against my fingers, sending a brief jolt of hope up through my arms and into my chest.

Then one night it happened. A single, small foot hesitantly pressed down on my hand, and then another, then another, and just like that, I was holding my hamster. I lifted her ever-so-slowly toward my body, heart pounding, determined not to destroy the fragile trust between us, and cradled her against me. And in that moment, all of the bites, the nibbles, the urine-soaked wood chips, the likely communicable hamster diseases, felt entirely, irrevocably, worth it.

“Hold on,” you may interrupt, with a justified roll of your eyes. “Do you mean to tell me that this nonsense with the hamster was, all along, merely an allegory for the power of your own vulnerability?” To that, I say: of course. What did you expect?

These days, we coexist, my hamster and I. She scurries around our sun-soaked apartment in her favorite ball, merrily bumping into walls and chewing on the rug, as I dine on Popeyes at my folding table and prepare to visit with human acquaintances. I don’t know if she loves me, or if she ever will. I don’t know if I love her, either. But we’re in this together. And for now, that’s enough.

Gretel Kauffman’s essay won second place in this magazine’s 2018 Young Alumni Essay Contest. She reports on politics and crime for the Times-News in Twin Falls, Idaho.