- Doing Good

- Goodness Gracious

- Pain Relievers

- Call It Human Nature

- Storylines

- The Sickness Swing

- The Sound of Sublime

- Moving Pictures

- Body Language

- A Quiet Incarnation

- Giving Upward

- Dauntless Luminescence

- The Shining Joy of Falling Flat on Your Face

My mother-in-law was good.

I bet that’s a sentence that hasn’t been written very often.

Betty Franklin was the kind of good one’s tempted to call saintly. But we shouldn’t call a good person a saint because that strips away her humanity — and responsibility for her actions. I’d wager she came out inclined toward goodness, but she was also good because she worked at it.

I’d known her for 20 years before I perceived that. Once, when the hall bathroom was occupied, I went into the one attached to her bedroom. There, on the mirror, was a Post-it note. “It’s not about YOU,” she admonished herself.

I’ve never seen a person less likely to think anything was about her, ever. She hated being the center of attention. In our early days of dating, Tommy and I drove to Alabama to take her out to lunch for her birthday, and I whispered news of our celebration to the waitress. Behold, in a moment the staff paraded over, clapping and singing “Happy Birthday,” forming a horseshoe around the table, presenting her with a fat slice of cake topped with a candle, cheering while she blew it out. It was the single cruelest thing I could have done to her. When I look back now, I’m amazed I didn’t know that.

She lived the quietest life imaginable. She liked to read the Bible in the early morning with her husband, holding hands. She liked to have dinner waiting for him when he came home from his mechanic shop. Her main activities were church and service work, bringing meals to elderly folks who couldn’t get out or ferrying them to their doctor appointments. Otherwise, she liked to be at home, where she managed the church’s prayer chain, and managed to stay incredibly busy helping everyone who needed her. A homebody? Hoo boy. She lived an hour and a half from the Gulf of Mexico but never went to the beach. The one time she was on an airplane was to fly to Chicago for our wedding. Did she hate it? She didn’t complain. But she went the rest of her life without duplicating the experience. How hard she must have prayed to keep that plane aloft, borne on eagle’s wings.

Her pleasures were simple; her greatest was being of use. Six of her 11 grandchildren lived next door and two others close by (the remaining three, our own, were a six-hour drive away, an almost unthinkable distance for her, though the Franklins did make the drive twice).

“Can I fix you something?” she’d ask when a small body flew though her back door. Even in her late 70s, her own body failing, she’d ask that, ratcheting her La-Z-Boy recliner up and using the remote to change her Hallmark movie to Blue’s Clues. She felt most herself when serving others invisibly, without praise. She hated to be photographed, was embarrassed by gifts, distrusted compliments, dreaded clothes shopping, avoided all things fussy or expensive. She played the piano — when she was alone in the house. Her “beauty regimen” consisted of washing her face with Pond’s cold cream. I never saw her drink a drop of alcohol. Married at age 18, she never had a job outside the home, never earned a single dollar. I never heard her ask for anything besides photos of her grandchildren. I never once heard her express a wish for anything advertised on television or mentioned by a neighbor.

Maybe I’m so fascinated with Betty’s goodness because we’re opposites in every way but the most important one — loving her son.

Tommy grew up in Dickinson, Alabama — a corner store and a cluster of houses surrounded by piney woods. His asthma was so bad when he was a boy that he couldn’t sleep at night. He had to sit up in bed because lying down made the wheezing worse. Betty sat in a chair beside his bed every night, talking with him, sometimes reading him stories so he wouldn’t feel scared when the breaths were difficult to snatch into his lungs. So he wouldn’t be alone with the owl-punctured dark.

Tommy tells me they’d talk for hours, until finally Betty would say, “Hear that?” and he’d listen, and there it was, the log truck rumbling down the road. The log trucks started right before dawn, so this was always a welcome rumble, the signal that soon Tommy would be able to breathe. She’d kiss his forehead and he’d slide down a bit in bed and she’d say, “You can sleep now, Sugar. You can sleep,” and she’d return to her bed for her own few short hours of slumber.

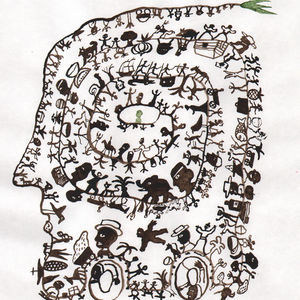

The world my husband grew up in could have embittered him. People treated like outcasts do grow bitter. Tommy didn’t want to hunt like the other boys, and he had no talent for fixing cars like his brother and father. What he wanted to do was draw cartoons and write books. Betty encouraged him, even as he moved out into a world that frightened her. He was the first person in his family to go to college. And then grad school, where we met, and where he started writing books.

A few years ago, one of his novels, Crooked Letter, Crooked Letter, was chosen as the Abitur for the south of Germany — the text on which German high school students studying English must write their exams. I tagged along on his reading tour. The most surreal moment was in the famed lecture hall at the University of Heidelberg, where I stood in the back, admiring its grand proportions, its arched ceiling, its dark walnut walls covered by oil paintings and lit by sconces. This university, I’d read, one of the world’s oldest, was chartered by Pope Urban VI in 1386, and has produced famous philosophers, writers, scientists, 29 Nobel laureates. Now it held a rapt, standing room only crowd listening to a first-generation college graduate from a hamlet in Alabama read his story about his people. And I so swooned for Betty, whose pride would have equaled my own, that — though it sounds melodramatic — I had to steady myself on the chair in front of me.

When people talk about legacies, they usually mean buildings or civic projects or financial gifts. Betty’s legacy is love. Her legacy is children who experienced it purely. Her legacy is the man I wed. Her legacy is my happy marriage.

She died of complications due to the Alzheimer’s that developed in her last few years, though those who knew her believe she started to die February 16, 2016, the day her husband of almost 60 years died. She took care of him from when he was in his 20s until he passed at 82, and toward the end, when his health was in decline, his body failing part by part, that caregiving became full time. When he was gone, she lost her job.

I never heard her complain until the end of her life, when Alzheimer’s started damaging her neural circuitry like rats nibbling the wiring in a house, invisible, insidious, the lights in her beautiful mind going out one by one. Before the diagnosis, but after we’d noticed worrying signs, we drove to her house to take her to a neurologist. We fetched lunch from Panera for all the grandkids, and Betty put her broccoli and cheddar soup in the fridge for later.

On the drive back from the tests, we heard her murmur something. “What, Mama?” Tommy asked. “I hope those kids don’t eat my soup,” she said. Tommy’s eyes met mine in the rearview. We didn’t need the neurologist to tell us she was sick. It was the meanest thing I’d heard her say in her entire life.

I lost a friend to cancer, and I used to think that was the worst death, to retain all of your faculties yet be unable to stop the body’s vicious revolt. Yet now that I’ve seen a death from Alzheimer’s, I’m not so sure. The slow, relentless, inexorable coring of someone’s personality, the deletions of memories, experiences, words, thoughts; this may in fact be worse. At the end, she couldn’t always recognize her children. There was so little left of her, but goodness remained. One of the last things she said to me was, “Can I fix you anything?”

Hear that, Betty? It’s the log trucks. You can sleep now, Sugar. You can sleep.

Beth Ann Fennelly, poet laureate of Mississippi, is the author of six books, most recently Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs.